Published August 2, 2023. Updated December 3, 2023. Open access. | Purchase book ❯ |

Ringed Spinytail-Iguana (Enyalioides annularis)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Sauria | Hoplocercidae | Enyalioides annularis

English common names: Ringed Spinytail-Iguana, Ringed Manticore.

Spanish common name: Mantícora de anillos.

Recognition: ♂♂ 31.2 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=13.7 cm. ♀♀ 24.2 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=11.8 cm..1,2 Enyalioides annularis is unmistakable among lizards in its area of distribution by having spines on the dorsal surface of the hind limbs and a thick tail with greatly enlarged, projecting, spinous scales (Fig. 1).1,2 Males are larger, more robust, and more brightly colored than females.1,2 This species coexists with other dwarf iguanas that are similar in size and coloration (E. microlepis and E. praestabilis), but these other wood lizards lack spines on the tail.3

Figure 1: Individuals of Enyalioides annularis from Arutam, Pastaza province, Ecuador. sa=subadult.

Natural history: Enyalioides annularis is an extremely rare dwarf iguana that inhabits pristine foothill rainforests as well as remnants of gallery forest in a matrix of pastures.1,2 Ringed Spinytail-Iguanas are diurnal, terrestrial, and gregarious.1,2 They live in self-dug burrows in colonies along walls of compact soil, with no more than one animal per hole.2 The burrows are about 20 cm in diameter, 1–3 m deep, and may be at ground level or above the ground. Most of the day, the lizards sit motionless in front of the entrances to their burrows and carefully observe their surroundings.2 If an insect or spider approaches, the manticores can be surprisingly quick and take the prey with one well-aimed leap.2 Then the lizard returns to its post at the cave entrance. When disturbed, individuals quickly flee into the burrows, inflate their body, and lock themselves strongly against the tunnel walls using their spiny scales.1 Females lay clutches of 2–5 eggs inside the burrows.1,2

Conservation: Vulnerable Considered to be facing a high risk of extinction in the mid-term future..4 Enyalioides annularis is listed in this category primarily on the basis of the species’ limited extent of occurrence (originally estimated to be under 20,000 km2, but see below), low population densities, fragmented distribution, and ongoing decline in the extent and quality of the upper Amazonian landscape.4 Since E. annularis is a burrowing specialist that exhibits high site fidelity, it is unlikely to recolonize areas following extirpation.4 Previously sampled colonies at Canelos and Bobonaza are now deserted.5 In Bobonaza and Arutam, local people report hunting these iguanas for food.5 Despite this, Arutam is still one of the last strongholds for the iguana.

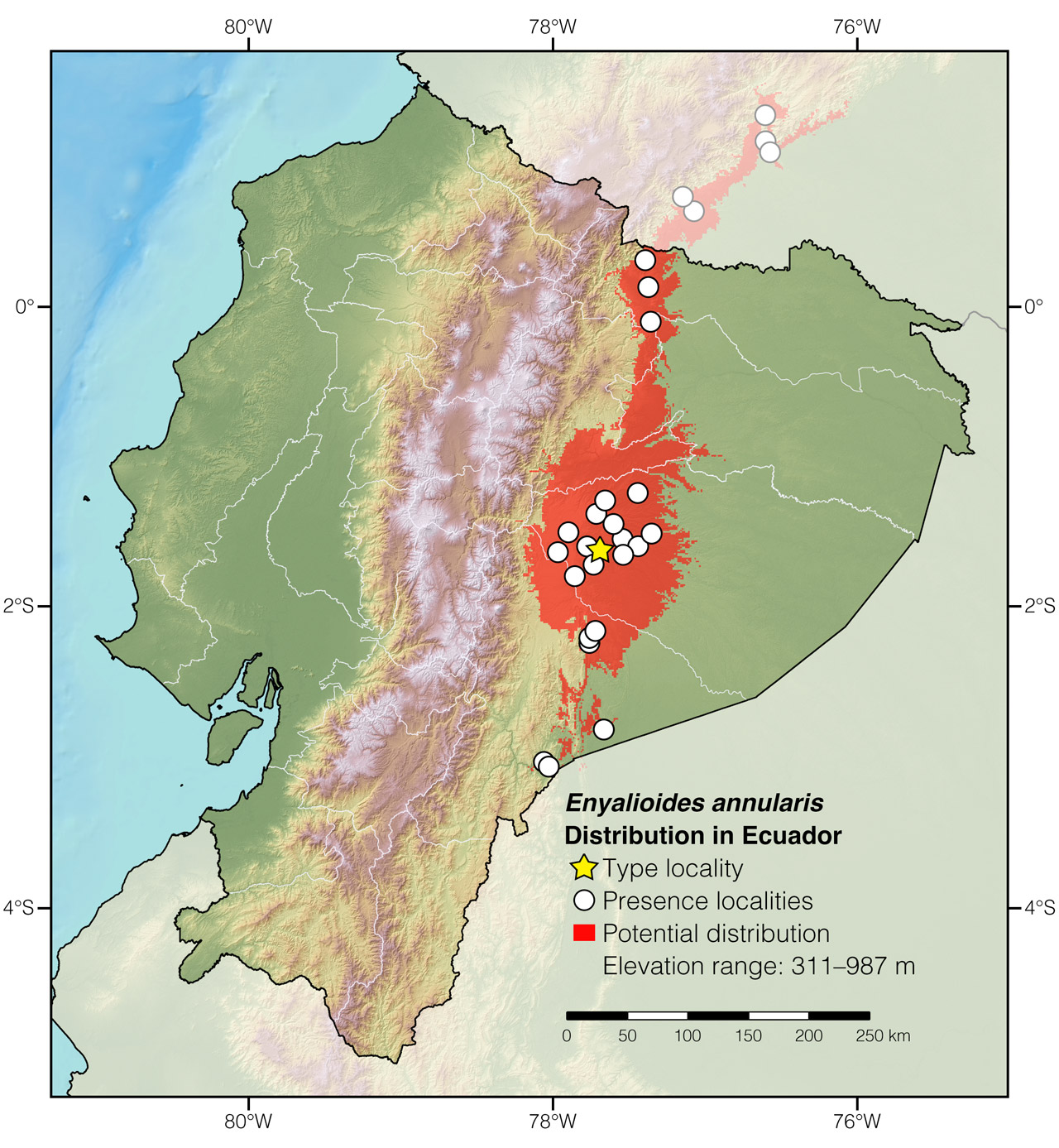

Distribution: Enyalioides annularis is native to an area of approximately 24,893 km2 along the Amazonian slopes of the Andes in Ecuador (Fig. 2) and Colombia.

Figure 2: Distribution of Enyalioides annularis in Ecuador. The star corresponds to the type locality: Canelos, Pastaza province. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The generic name Enyalioides, which comes from the Latin words Enyalius (a genus of neotropical lizards) and the suffix oides (=similar to), refers to the similarity between lizards of the two genera. The specific epithet annularis (=ringed in Latin) refers to the ringed tail.6

See it in the wild: Ringed Spinytail-Iguanas used to be locally common in some parts of the Ecuadorian Amazon, but healthy colonies are now extremely difficult to find. Vagrant individuals are reported from time to time around Arutam, Arajuno, and Macuma, but these observations probably correspond to individuals displaced by deforestation.

Acknowledgments: Special thanks to Søren Hoff Brøndum and Linda Vargas for helping us locate the two individuals of Enyalioides annularis pictured in Fig. 1.

Author: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

Photographer: Amanda QuezadabAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,cAffiliation: Laboratorio de Herpetología, Universidad del Azuay, Cuenca, Ecuador.

How to cite? Arteaga A (2023) Ringed Spinytail-Iguana (Enyalioides annularis). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/ATHX1802

Literature cited:

- Torres-Carvajal O, Etheridge R, de Queiroz K (2011) A systematic revision of Neotropical lizards in the clade Hoplocercinae (Squamata: Iguania). Zootaxa 2752: 1–44. DOI: 10.11646/zootaxa.2752.1.1

- Köhler G, Seipp R, Moya S, Almendáriz A (1999) Zur Kenntnis von Morunasaurus annularis (O’Shaughnessyi 1881). Salamandra 35: 181–190.

- Torres-Carvajal O, de Queiroz K, Etheridge R (2009) A new species of iguanid lizard (Hoplocercinae, Enyalioides) from southern Ecuador with a key to eastern Ecuadorian Enyalioides. ZooKeys 27: 59–71. DOI: 10.3897/zookeys.27.273

- Cisneros-Heredia DF (2016) Morunasaurus annularis. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org. DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T203069A2759780.en

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- O’Shaughnessy AWE (1881) An account of the collection of lizards made by Mr. Buckley in Ecuador, and now in the British Museum, with descritions of the new species. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 49: 227–245.

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Enyalioides annularis in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used. Asterisk (*) indicates type locality.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Colombia | Cauca | Villa Iguana | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2011 |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Desembocadura Río Indiyaco | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2011 |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Estación de bombeo Guamuéz | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2011 |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Puerto Limón | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2011 |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Río Guamués | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Centro Shuar Kenkuim | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2011 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Centro Shuar Kiim | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2011 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Centro Shuar Mutinza | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2011 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Cusuime | Ortega-Andrade 2010 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Macuma | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Valle del Río Santiago | Online multimedia |

| Ecuador | Napo | Campamento Codo Bajo | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2011 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Alto Curaray | Köhler et al. 1999 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Alto Río Arajuno | Wiens and Etheridge 2003 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Alto Río Conambo | Van Denburgh 1912 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Arutam | Köhler et al. 1999 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Bobonaza | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2011 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Bosque Protector Yawa Jee | Köhler et al. 1999 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Canelos* | O’Shaughnessyi 1881 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Palora, 30 km E of | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Huiyayacu | USNM 200796; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Lliquino | USNM 200804; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Oglán | Köhler et al. 1999 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Pucayacu | USNM 200811; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Villano | USNM 200813; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Lumbaqui, 15 km ENE of | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2011 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Reserva Ecológica Cofán Bermejo | Borman et al. 2007 |