Published March 8, 2024. Open access. | Purchase book ❯ |

Rusty-fronted Whipsnake (Chironius leucometapus)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Serpentes | Colubridae | Chironius leucometapus

English common name: Rusty-fronted Whipsnake.

Spanish common name: Serpiente látigo de hocico rojizo.

Recognition: ♂♂ 195 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=147.4 cm. ♀♀ 174.3 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=131.1 cm..1,2 Chironius leucometapus can be identified by the following combination of features: 10 rows of dorsal scales at mid-body, keeled paravertebral scales, an entire anal plate, and a unique coloration.1,2 The dorsum is mossy green with a reddish patch on the snout (Fig. 1). This species differs from C. fuscus by having a rusty colored snout and by lacking a dark postocular stripe.1,2 It differs from C. monticola, C. exoletus, and C. multiventris by having a red snout and less dorsal scales at mid-body (12 in the other species).1

Figure 1: Illustration of an adult male of Chironius leucometapus from Ecuador.

Natural history: Chironius leucometapus is an extremely rare diurnal and semi-arboreal snake that inhabits pristine lowland and foothill rainforests.1 Rusty-fronted Whipsnakes have been seen frantically foraging on the forest floor during the daytime or roosting on shrubs less than 2 m above the ground.3 Not much is known about the diet of this species: only a frog of the family Leptodactylidae was found in the stomach of a museum specimen.1 However, like other members of the genus Chironius, this species probably specializes on frogs. The egg deposition and hatching of C. leucometapus coincides with the local rainy season.2 Gravid females have been found to contain 6–8 oviductal eggs.1,2 When cornered, whipsnakes tend to inflate the neck, open the mouth aggressively, and strike. However, they are not venomous.

Conservation: Least Concern Believed to be safe from extinction given current circumstances..4 Chironius leucometapus is listed in this category primarily because the species is widely distributed, occurs in protected areas, and is able to tolerate some degree of habitat disturbance so long as forest remain.4 However, being extremely rare, nothing is known about the population trend of this species. The decline in the number of anuran prey due to pollution and emerging diseases could have a negative impact on this exclusively frog-eating snake.

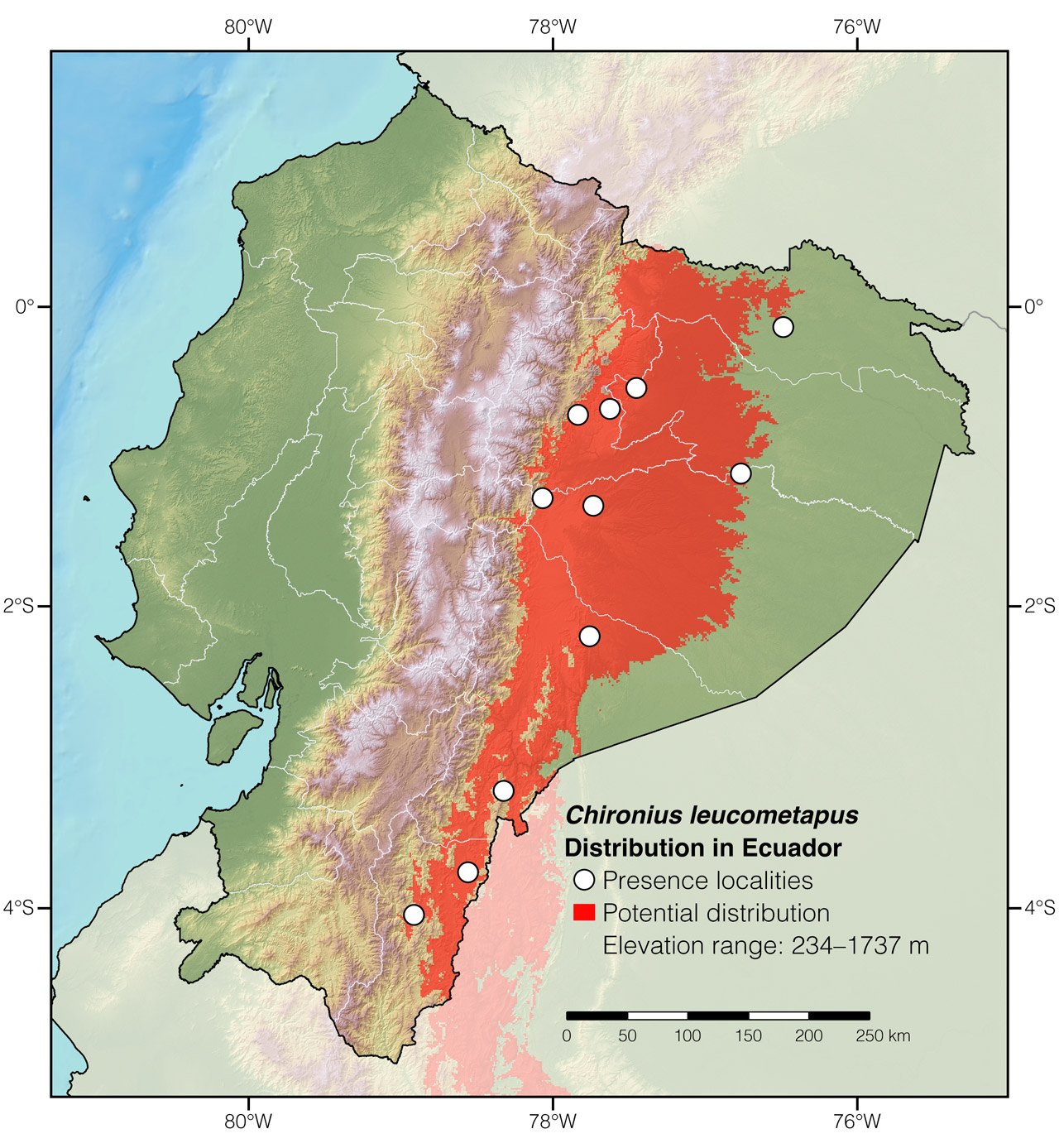

Distribution: Chironius leucometapus is widely distributed along the Amazonian foothills of the Andes of Ecuador and Perú (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Distribution of Chironius leucometapus in Ecuador. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The name Chironius was coined by Leopold Fitzinger in 1826, but likely originated in 1790 with Blasius Merrem, who used the common name “Chiron’s Natter” for Linnaeus’ Coluber carinatus.5 In Greek mythology, Chiron was a centaur reputed for his healing abilities. Likewise, in ancient Greek civilization, sick people hoping for a cure flocked to temples where sacred snakes were carefully tended and presented to the sufferers. The specific epithet leucometapus comes from the Greek words leuco (=white) and metapon (=forehead), and refers to the diagnostic pale forehead coloration of preserved specimens (rusty in live specimens).1,2

See it in the wild: Rusty-Fronted Whipsnakes can be seen at a rate of about once every few years. The only Ecuadorian locality having more than two records of this species is Río Bigal Biological Reserve, where the snakes were found by scanning understory vegetation along trails at dusk.

Authors: Esteban Garzón-FrancoaAffiliation: Colecciones Biológicas de la Universidad CES (CBUCES), Facultad de Ciencias y Biotecnología, Universidad CES, Medellín, Colombia. and Laura Gómez-MesabAffiliation: Escuela de Ciencias Aplicadas e Ingeniería, Universidad EAFIT, Medellín, Colombia.

Editor: Alejandro ArteagacAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

Illustrator: Valentina Nieto Fernández

How to cite? Garzón-Franco E, Gómez-Mesa L (2024) Rusty-fronted Whipsnake (Chironius leucometapus). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/KQLH9630

Literature cited:

- Dixon JR, Wiest Jr JA, Cei JM (1993) Revision of the Neotropical snake genus Chironius Fitzinger (Serpentes, Colubridae). Museo Regionale di Scienze Naturali di Torino, Torino, 280 pp.

- Torres-Carvajal O, Koch C, Valencia JH, Venegas PJ, Echevarría LY (2019) Morphology and distribution of the South American snake Chironius leucometapus (Serpentes: Colubridae). Phyllomedusa 18: 241–254. DOI: 10.11606/issn.2316-9079.v18i2p241-254

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- Chavez G, Venegas P (2021) Chironius leucometapus. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org. DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-3.RLTS.T147031512A147032055.en

- Merrem B (1790) Beitrage zur Naturgeschichte. Duisburg um Lemgo, Berlin, 141 pp.

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Chironius leucometapus in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Concesión minera Kinross | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Mutintz | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Yawi, 4 km SW of | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Napo | Cotundo, 12 km NW of | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Wild Sumaco Wildlife Sanctuary | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Reserva Río Bigal | García et al. 2021 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Oglán Alto | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Reserva Privada Ankaku | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Shiripuno Lodge | Photo by Rudy Gelis |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | San Pablo de Kantesiya | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Timbara | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Perú | San Martín | El Dorado | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2019 |

| Perú | San Martín | La Cueva | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2019 |

| Perú | San Martín | Paitoja | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2019 |