Published February 11, 2023. Updated March 7, 2024. Open access. | Purchase book ❯ |

Yellow-spotted Whipsnake (Chironius flavopictus)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Serpentes | Colubridae | Chironius flavopictus

English common names: Yellow-spotted Whipsnake, Yellow-spotted Keelback.

Spanish common names: Granadilla, huaijera (Ecuador); granadilla, lomo de machete de puntos amarillos, jueteadora (Colombia).

Recognition: ♂♂ 205.4 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=138.8 cm. ♀♀ 201.3 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=137.7 cm..1 Chironius flavopictus can be differentiated from other snakes by having 12 dorsal scale rows at mid-body, keeled paravertebral scales, and a unique coloration.1–3 The dorsum is black to olive with the first row of dorsal scales painted with orange or yellow anteriorly and grayish or bluish posteriorly (Fig. 1).1–3 In Ecuador, similar species that may be found living alongside C. flavopictus are C. exoletus and C. grandisquamis, but none of these have a dorsal pattern of spots on a dark background. Chironius flavopictus further differs from C. grandisquamis by having a higher number of dorsal scale rows at mid-body (10 in C. grandisquamis).1

Figure 1: Individuals of Chironius flavopictus: Tundaloma Lodge, Esmeraldas province, Ecuador (); Canopy Camp Lodge, Darién province, Panamá ().

Natural history: Chironius flavopictus is a rarely-seen diurnal and semi-arboreal snake that inhabits old-growth to heavily disturbed evergreen lowland forests, gallery forests, plantations, and rural gardens.1–4 At night, these snakes sleep coiled on branches of bushes and trees 0.3–15 m above the ground, usually along bodies of water.1–4 Yellow-spotted Whipsnakes actively forage on the forest floor or on tree trunks during the day.1,3 Their diet is composed exclusively of frogs (of the genera Phyllomedusa, Smilisca, Lectodactylus, and Pristimantis). 2–6 There are records of snakes (genus Leptodeira) preying upon juveniles of C. flavopictus.7 These snakes can be aggressively defensive, vibrating the tail and striking when handled or cornered,4 but are otherwise harmless to humans.8 The clutch size consists of 10 eggs at a time.9

Conservation: Least Concern Believed to be safe from extinction given current circumstances..10 Chironius flavopictus is listed in this category because the species is widely distributed and it is unlikely to be declining fast enough to qualify for a more threatened category. Although little is known about threats to this species, deforestation and the decline in the number of anuran prey due to pollution and emerging diseases could have a negative localized impact on some populations.5 Minor, but ongoing threats to C. flavopictus include mortality from vehicular traffic and direct killing at the hands of villagers.4,11

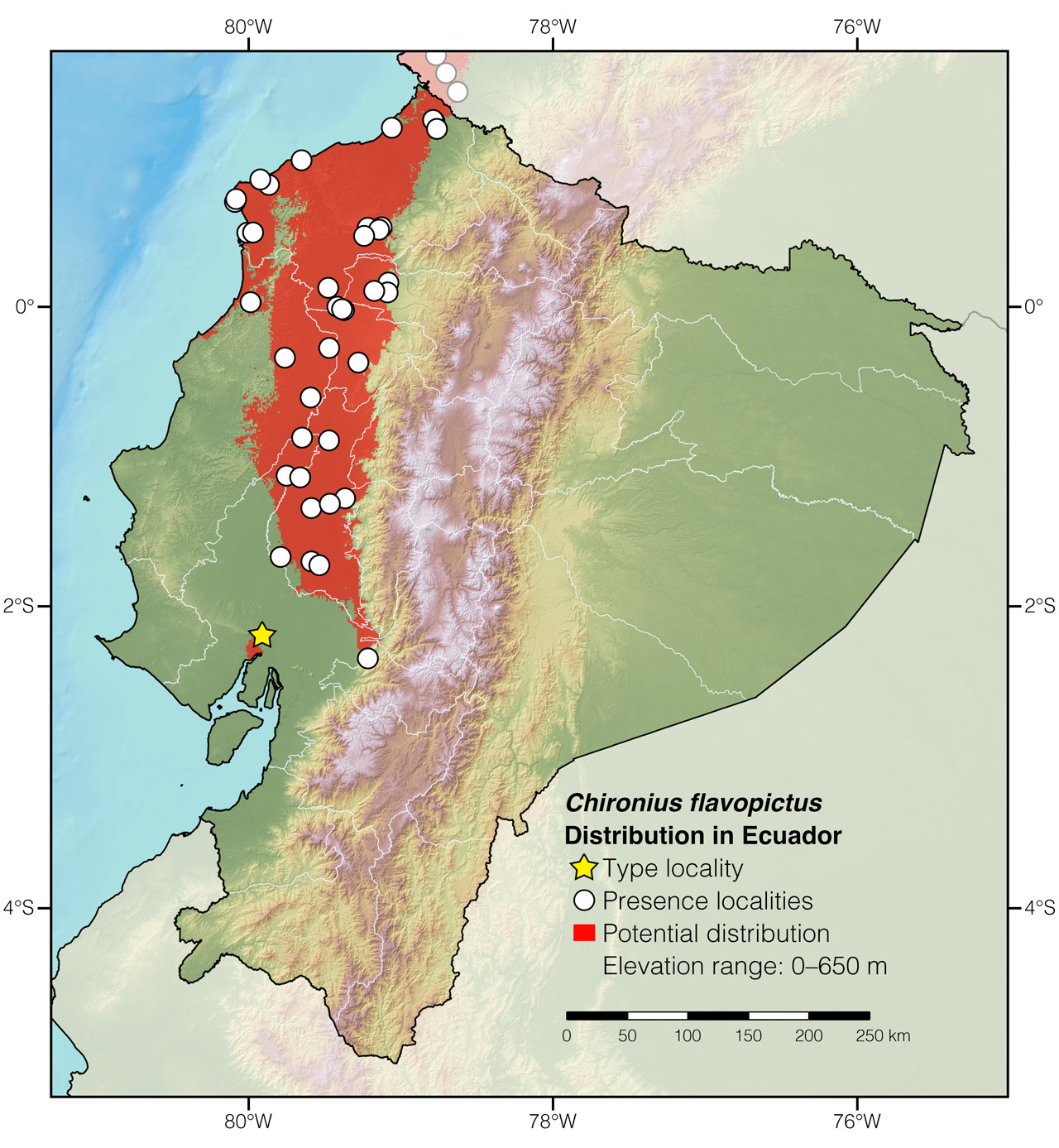

Distribution: Chironius flavopictus is native to the Mesoamerican and Chocoan lowlands from Costa Rica to western Ecuador (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Distribution of Chironius flavopictus in Ecuador. The star corresponds to the type locality: Guayaquil, Guayas province. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The name Chironius was coined by Leopold Fitzinger in 1826, but likely originated in 1790 with Blasius Merrem, who used the common name “Chiron’s Natter” for Linnaeus’ Coluber carinatus.12 In Greek mythology, Chiron was a centaur reputed for his healing abilities. Likewise, in ancient Greek civilization, sick people hoping for a cure flocked to temples where sacred snakes were carefully tended and presented to the sufferers. Therefore, Chironius likely refers to the healing power of snakes, a belief that lies at the foundation of medicine and crosses many cultures worldwide.13,14 The specific epithet flavopictus comes from the Latin words flavus (=yellow) and pictus (=painted)15 and refers to the dorsal coloration.1

See it in the wild: Yellow-spotted Whipsnakes are seen at a rate of about once every few months in forested localities throughout their area of distribution in Ecuador. The locality having the greatest number of observations is Rancho Suamox, Pichincha province. These snakes can be spotted at night, sleeping on vegetation along bodies of water or foraging on the ground during sunny days.

Special thanks to Mami Okura for symbolically adopting the Yellow-spotted Whipsnake and helping bring the Reptiles of Ecuador book project to life.

Click here to adopt a species.

Authors: Laura Gómez-MesaaAffiliation: Escuela de Ciencias Aplicadas e Ingeniería, Universidad EAFIT, Medellín, Colombia. and Esteban Garzón-FrancobAffiliation: Colecciones Biológicas de la Universidad CES (CBUCES), Facultad de Ciencias y Biotecnología, Universidad CES, Medellín, Colombia.

Editor: Alejandro ArteagacAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

Photographer: Jose VieiradAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,eAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Gómez-Mesa L, Garzón-Franco E (2024) Yellow-spotted Whipsnake (Chironius flavopictus). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/EKEB9848

Literature cited:

- Dixon JR, Wiest Jr JA, Cei JM (1993) Revision of the Neotropical snake genus Chironius Fitzinger (Serpentes, Colubridae). Museo Regionale di Scienze Naturali di Torino, Torino, 280 pp.

- Rodríguez-Guerra A (2020) Chironius flavopictus. In: Torres-Carvajal O, Pazmiño-Otamendi G, Ayala-Varela F, Salazar-Valenzuela D (Eds) Reptiles del Ecuador Versión 2021. Museo de Zoología, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador. Available from: https://bioweb.bio

- Savage JM (2002) The amphibians and reptiles of Costa Rica, a herpetofauna between two continents, between two seas. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 934 pp.

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- Barquero-González JP, Stice TL, Gómez G, Monge-Nájera J (2020) Are tropical reptiles really declining? A six-year survey of snakes in a tropical coastal rainforest: role of prey and environment. Revista de Biología Tropical 68: 336–343. DOI: 10.15517/rbt.v68i1.38555

- Roberto IJ, Ramos Souza A (2020) Review of prey items recorded for snakes of the genus Chironius (Squamata, Colubridae), including the first record of Osteocephalus as prey. Herpetology Notes 13: 1–5.

- Escalante RN, Acuña CA, Acuña AA (2021) Second report of ophiophagy in a cat-eyed snake (Leptodeira sp.) in Costa Rica. Reptiles & Amphibians 28: 102–103. DOI: 10.17161/randa.v28i1.15119

- Lotzkat S (2014) Diversity, taxonomy, and biogeography of the reptiles inhabiting the highlands of the Cordillera Central (Serranía de Talamanca and Serranía de Tabasará) in western Panama. PhD thesis, Goethe-Universität in Frankfurt am Main, 931 pp.

- Leenders T (2019) Reptiles of Costa Rica: a field guide. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, 625 pp.

- Reyes-Puig C (2015) Un método integrativo para evaluar el estado de conservación de las especies y su aplicación a los reptiles del Ecuador. MSc thesis, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador, 73 pp.

- Juan-P Durango, field observation.

- Merrem B (1790) Beitrage zur Naturgeschichte. Duisburg um Lemgo, Berlin, 141 pp.

- Nayernouri T (2010) Asclepius, caduceus, and simurgh as medical symbols. Archives of Iranian Medicine 13: 61–68.

- Güner E, Şeker KG, Güner Ş Why is the medical symbol a snake? Istanbul Medical Journal 20: 172–175. DOI: 10.4274/imj.galenos.2018.65902

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington D.C., 882 pp.

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Chironius flavopictus in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used. Asterisk (*) indicates type locality.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Colombia | Chocó | Quibdó | Photo by John Culebra |

| Colombia | Nariño | Estación Mar Agrícola | Pinto-Erazo et al. 2020 |

| Colombia | Nariño | Tangareal del Mira | Photo by Andrés Mauricio Forero |

| Colombia | Nariño | Vicinity of La Guayacana | Dixon et al. 1993 |

| Colombia | Valle del Cauca | Represa del Alto Anchicayá | ICZ-H026; Santiago Orozco field data |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Avenida de los Puentes | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Caimito | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Canandé Biological Reserve | Photo record; this work |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Centro de Fauna Silvestre James Brown | Photo by Salvador Palacios |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Finca de Carlos Vásquez | Photo by Carlos Vásquez |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Finca de Germán Cortez | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Finca La Cucaracha | Photo by Pablo Loaiza |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Hacienda San Miguel | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Itapoa Reserve | Photo by Raúl Nieto |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | La Pierina | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | La Tola | Dixon et al. 1993 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | La Unión | MHNG 2512.041; collection database |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Quingüe | Photo by Rubén Jarrín |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Río Achiote | Photo record; this work |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Same | MHNG 2309.073; collection database |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | San Lorenzo, 7 km SE of | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Tres Vías | QCAZ 6440; Torres-Carvajal et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Tundaloma Lodge | Photo record; this work |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Cabeceras del Río Congo | Dixon et al. 1993 |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Dos Bocas | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Guayaquil* | Dixon et al. 1993 |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Km 507 | Photo by Eduardo Zavala |

| Ecuador | Los Ríos | Cantón de Pueblo Viejo | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Los Ríos | El Señor de los Caballos | Photo record; this work |

| Ecuador | Los Ríos | Estero de Damas | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Los Ríos | Finca Elba | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Los Ríos | Jauneche | Juan Carlos Sánchez |

| Ecuador | Los Ríos | Macul | MZUA.RE.0145; examined |

| Ecuador | Los Ríos | Manga del Cura | Photo by Edison Araguillin |

| Ecuador | Los Ríos | Recinto La Muralla | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Los Ríos | Río Bajaña | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Cerro Pata de Pájaro | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Manabí | El Carmen | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Manabí | La Crespa | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Manabí | San Ramón | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | La Celica | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Pedro Vicente Maldonado, 2 km E of | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Rancho Suamox | Photo by Rafael Ferro |

| Ecuador | Santo Domingo de los Tsáchilas | Empacadora Fgenterprise | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Santo Domingo de los Tsáchilas | Reserva Forestal La Perla | Photo by Plácido Palacios |