Published February 3, 2024. Open access. | Purchase book ❯ |

Pipe Snake (Anilius scytale)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Serpentes | Aniliidae | Anilius scytale

English common name: Pipe Snake, South American False Coral Snake, Coral Cylinder Snake.

Spanish common name: Falsa coral cilíndrica.

Recognition: ♂♂ 90.4 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=87.7 cm. ♀♀ 118.4 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=114.8 cm..1,2 Anilius scytale can be identified by having a cylindrical body, smooth scales, and a pair of pelvic spurs.3,4 The dorsum is orange-red with black bands that may extend onto the belly (Fig. 1).5,6 Anilius scytale could be confused with true coral snakes (Micrurus) or with other false corals such as Atractus elaps. However, the eye of A. scytale is extremely small and beneath a single large scale, whereas in corals and their mimics it is surrounded by several scales.5 Also, the tail of A. scytale is wide, short, and with a rounded-tip, whereas in coral snakes the tail is long and slender.

Figure 1: Adult individual of Anilius scytale from Huella Verde Lodge, Pastaza province, Ecuador.

Natural history: Anilius scytale is a rarely seen fossorial snake that exhibits terrestrial and aquatic activity.7 This species occurs in primary terra-firme rainforest and seasonally flooded forest, but has also been recorded in clearings, crops, and rural gardens.5,8 Pipe Snakes spend most of the time hidden under logs,7 buried underground, or in leaf-litter,2,6 but compaction of the soil can force them out. Otherwise, these snakes come out only when searching for food,7 with foraging occurring on leaf-litter, soil, or mud during the day or at night.9 Pipe Snakes are active hunters and their diet is based primarily on long-bodied vertebrates, which are consumed starting by the head.9 Prey items include swamp eels,9 amphisbaenians,9,10 caecilians,9,11 and snakes (including Tantilla melanocephala, Atractus torquatus, and even conspecifics).7 These snakes are calm and rarely attempt to strike, but their bite can be powerful.8 Their defensive display is similar to a coral snake’s, flattening the body dorso-ventrally while hiding the head under body coils and raising the tail.6,12 Breeding takes place year-round, with a peak in the rainy season.1,13 Females “give birth” (the eggs hatch within the mother) to 2–37 young.1,13,14 Males with mating interest are presumed to engage in combat, however there is no confirmed report of this behavior.1 Even so, in Colombia, mating events were recorded in which the male held the female by the head, biting her, followed by copulation.15

Conservation: Least Concern Believed to be safe from extinction given current circumstances..16 Anilius scytale is listed in this category mainly on the basis of the species’ wide distribution, occurrence in protected areas, and presumed large and stable populations.16 Although the loss and fragmentation of the Amazonian landscape could lead some populations to disappear, the majority of the habitat of A. scytale is in good condition. Therefore, the species is considered to be facing no major immediate extinction threats.

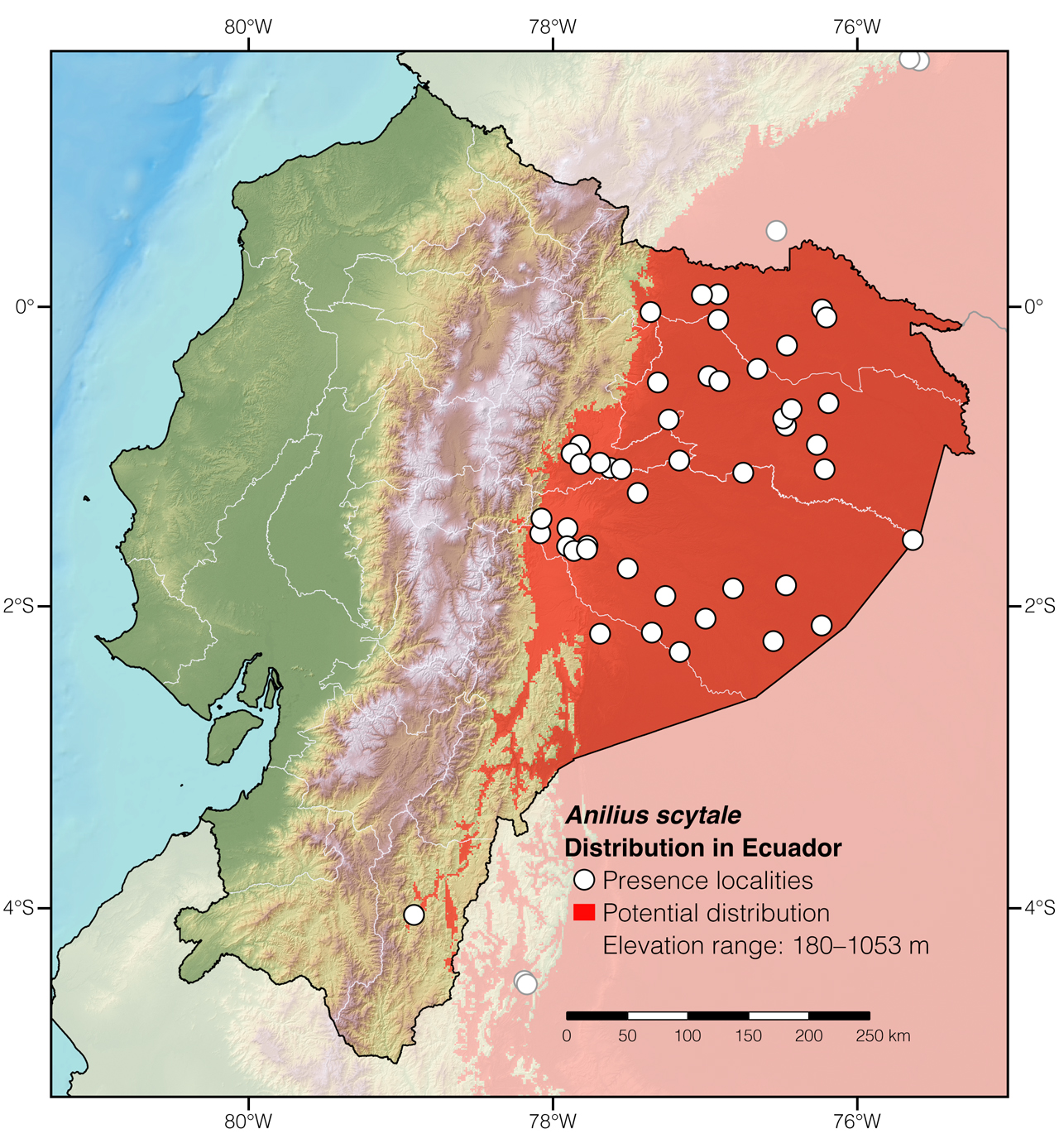

Distribution: Anilius scytale occurs throughout the entire Amazon basin in Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador (Fig. 2), Guiana, French Guiana, Perú, Suriname, and Venezuela. The species also occurs in the Colombian-Venezuelan Llanos as well as on Trinidad Island, occupying an area of approximately 831,349 km2.17

Figure 2: Distribution of Anilius scytale in Ecuador. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The generic name Anilius comes from the Greek words an (=lacking) and helios (=the sun), and refers to the fossorial habits of the species.18 The specific epithet scytale comes from the greek skytala (=cylinder)19 and refers to the rounded tail.

See it in the wild: In Ecuador, Pipe Snakes are recorded at a rate of about once every few months. The area having the greatest number of recent observations of this species is Canelos, Pastaza province.

Special thanks to Andrew Durso for symbolically adopting the Pipe Snake and helping bring the Reptiles of Ecuador book project to life.

Click here to adopt a species.

Authors: Iván Niño-Cárdenas,aAffiliation: Laboratorio de Anfibios, Instituto de Ciencias Naturales, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá, Colombia. Andrés F. Aponte-Gutiérrez,bAffiliation: Grupo de Biodiversidad y Recursos Genéticos, Instituto de Genética, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá, Colombia.,cAffiliation: Fundación Biodiversa Colombia, Bogotá, Colombia. and Juan Acosta-OrtizdAffiliation: Universidad de los Llanos. Villavicencio, Colombia.

Editor: Alejandro ArteagaeAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.

Photographer: Alejandro ArteagaeAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Niño-Cárdenas I, Aponte-Gutiérrez A, Acosta-Ortiz J (2024) Pipe Snake (Anilius scytale). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/INQZ9733

Literature cited:

- Maschio GF, da Costa Prudente AL, de Lima AC, Feitosa DT (2007) Reproductive biology of Anilius scytale (Linnaeus, 1758) (Serpentes, Aniliidae) from eastern Amazonia, Brazil. South American Journal of Herpetology 2: 179–183. DOI: 10.2994/1808-9798(2007)2[179:RBOASL]2.0.CO;2

- Dixon JR, Soini P (1986) The reptiles of the upper Amazon Basin, Iquitos region, Peru. Milwaukee Public Museum, Milwaukee, 154 pp.

- de Fraga R, Lima AP, da Costa Prudente AL, Magnusson WE (2013) Guia de cobras da região de Manaus - Amazônia Central. Editopa Inpa, Manaus, 303 pp.

- Natera-Mumaw M, Esqueda-González LF, Castelaín-Fernández M (2015) Atlas serpientes de Venezuela. Dimacofi Negocios Avanzados S.A., Santiago de Chile, 456 pp.

- Duellman WE (1978) The biology of an equatorial herpetofauna in Amazonian Ecuador. Publications of the Museum of Natural History, University of Kansas 65: 1–352.

- Duellman WE (2005) Cusco amazónico: the lives of amphibians and reptiles in an Amazonian rainforest. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, 433 pp.

- Martins M, Oliveira ME (1998) Natural history of snakes in forests of the Manaus region, Central Amazonia, Brazil. Herpetological Natural History 6: 78–150.

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- Maschio GF, da Prudente ALC, da Rodrigues FS, Hoogmoed MS (2010) Food habits of Anilius scytale (Serpentes: Aniliidae) in the Brazilian Amazonia. Zoologia 27: 184–190. DOI: 10.1590/S1984-46702010000200005

- dos Santos-Costa MC, Maschio GF, da Costa Prudente AL (2015) Natural history of snakes from Floresta Nacional de Caxiuanã, eastern Amazonia, Brazil. Herpetology Notes 8: 69–98.

- Villacampa J, Whitworth A (2016) Predation of Oscaecilia bassleri (Gymnophiona: Caecilidae) by Anilius scytale (Serpentes: Aniliidae) in southeast Peru. Cuadernos de Herpetología 30: 29–30. DOI: 10.31017/6298

- Sawaya RJ (2010) The defensive tail display of Anilius scytale (Serpentes: Aniliidae). Herpetology Notes 3: 249–250.

- Cisneros-Heredia DF (2005) Anilius scytale (Red Pipesnake): reproduction. Herpetological Bulletin 92: 28–29.

- Cunha OR, do Nascimento FP (1981) Ofídios da Amazônia: XIII – Observações sobre a viviparidade em ofídios do Pará e Maranhão (Ophidia: Anilidae, Boidae, Colubridae e Viperidae). Boletim do Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi 109: 1–20.

- Field notes of Andres Aponte-Gutiérrez.

- Arredondo JC, Castañeda MR, Cisneros-Heredia DF, Velasco J, Hoogmoed MS, Nogueira CC, Schargel W, Rivas G, Martins MRC (2013) Anilius scytale. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org. DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-2.RLTS.T167047A15204086.en

- Nogueira CC, Argôlo AJS, Arzamendia V, Azevedo JA, Barbo FE, Bérnils RS, Bolochio BE, Borges-Martins M, Brasil-Godinho M, Braz H, Buononato MA, Cisneros-Heredia DF, Colli GR, Costa HC, Franco FL, Giraudo A, Gonzalez RC, Guedes T, Hoogmoed MS, Marques OAV, Montingelli GG, Passos P, Prudente ALC, Rivas GA, Sanchez PM, Serrano FC, Silva NJ, Strüssmann C, Vieira-Alencar JPS, Zaher H, Sawaya RJ, Martins M (2019) Atlas of Brazilian snakes: verified point-locality maps to mitigate the Wallacean shortfall in a megadiverse snake fauna. South American Journal of Herpetology 14: 1–274.

- Savage JM, Boundy J (2012) On the type species of the snake generic name Anilios Gray, 1845 (Serpentes: Typhlopidae). Herpetological Review 43: 537–538.

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington D.C., 882 pp.

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Anilius scytale in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Colombia | Caquetá | Florencia, Orteguaza river | MLS-372; Cárdenas Hincapié & Lozano Bernal 2023 |

| Colombia | Caquetá | San Vicente del Caguán | MLS-1610; Cárdenas Hincapié & Lozano Bernal 2023 |

| Colombia | Caquetá | Vereda La Primavera | UAM-R-0411; Ruiz Valderrama 2023 |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Puerto Asís | MLS-374; Cárdenas Hincapié & Lozano Bernal 2023 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Macuma | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Archidona | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Huaorani Lodge | Photo by Etienne Littlefair |

| Ecuador | Napo | Jatun Sacha Biological Reserve | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Misahuallí | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Muyuna | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Napo | Puerto Napo | Medrano-Vizcaíno & Brito-Zapata 2021 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Río Suno | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Tena | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Amarum | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Centinela de la Patria | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Cononaco | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Cononaco | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Dicaro, 3 km NW of | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Platforma Wati | Rodríguez–Guerra & Mármol–Guijarro 2020 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Pompeya Sur–Iro highway, km 53 | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | San José de Payamino | Maynard et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Tiputini Biodiversity Station | Cisneros-Heredia 2003 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Yasuní Scientific Station | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | 10 de agosto | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Alto Curaray | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Balsaura | Ortega-Andrade 2010 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Canelos | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Chontoa | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Finca Heimatlos | Photo by Ferhat Gundogdu |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Huella Verde Lodge | This work; Fig. 1 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Juyuintza | Ortega-Andrade 2010 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Mashient | Cisneros-Heredia 2004 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Montalvo | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Numpai | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Pozo Misión | Almendariz 1986 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Rutuno | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Sarayacu | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Shell | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Shiripuno Lodge | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Tambo | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Tinajas del Río Anzu | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Caiman Lodge | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Dashiño | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | El Eno, 2 km S of | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Lago Agrio* | Duellman 1978 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Limoncocha | Photo by Eric Osterman |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Nicky Amazon Lodge | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | San Pablo de Kantesiya | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Santa Cecilia | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Timbara | Photo by Darwin Núñez |

| Perú | Amazonas | Huampami | MVZ 175000; VertNet |

| Perú | Amazonas | La Poza | MVZ 163243; VertNet |

| Perú | Amazonas | San Antonio, Río Cenepa | VertNet |