Published October 5, 2021. Updated January 29, 2024. Open access. | Purchase book ❯ |

Puyango Whorltail-Iguana (Stenocercus puyango)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Sauria | Tropiduridae | Stenocercus puyango

English common name: Puyango Whorltail-Iguana.

Spanish common name: Guagsa de Puyango.

Recognition: ♂♂ 30.9 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=11.5 cm. ♀♀ 22.1 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=8.2 cm..1,2 The Puyango Whorltail-Iguana (Stenocercus puyango) differs from most other medium-sized diurnal and terrestrial lizards in its area of distribution (particularly species in the family Teiidae) by having keeled dorsal scales with pointed ends instead of granular scales (Fig. 1).3 Stenocercus puyango differs from S. iridescens by having a post-femoral mite pocket and posterior circumorbital scales.4 From S. limitaris, it differs by having smooth, instead of keeled, head and ventral scales.4 From Microlophus occipitalis, it differs by having 4–6, instead of 7–8, supraocular scales.4,5 Males of S. puyango are larger than females and have a brighter ventral coloration.1,4

Figure 1: Individuals of Stenocercus puyango from Loja province, Ecuador: Jorupe Reserve () La Ceiba Reserve (). j=juvenile.

Natural history: Stenocercus puyango is a diurnal and terrestrial lizard that inhabits areas of dry lowland shrubland and deciduous to semi-deciduous lowland forest.1,4 This species prefers the forest interior or shrub vegetation, but can also be found along forest borders6 and in human-modified environments such as farms with crops, pastures, and infrastructures.7,8 Puyango Whorltail-Iguanas move actively on the forest floor, with a peak of activity during the hot sunny hours,9 being found basking on sand, large stones, or logs up to 50 cm above the ground.1,7–11 When inactive, individuals are found under plants or rocks,2,11 or sleeping on tangled vegetation up to 2 m above the ground.2 The diet in this species includes a wide variety of arthropods, mainly insects of the order Hymenoptera.7 There are records of snakes (Oxybelis transandinus),12 owls (Pulsatrix perspicillata),13 and tarantulas2 preying upon individuals of this species.13 Adult males defend territories by performing push-up displays.1 Gravid females have been found to contain two eggs.4

Conservation: Least Concern Believed to be safe from extinction given current circumstances..14 Stenocercus puyango is included in this category because the species is relatively common, distributed over an area greater than 10,000 km2, and is currently facing no major immediate extinction threats.14 However, in Ecuador, the species qualifies for a threatened conservation category.15 Based on maps of Ecuador’s vegetation cover published in 2012,16 an estimated ~48% of the native dry forest habitat of S. puyango has already been destroyed in this country, mostly due to cattle ranching. Fortunately, Peruvian populations appear to be in better shape, and a major part of the species’ range is in the Cerros Amotape National Park and Tumbes Reserved Zone.

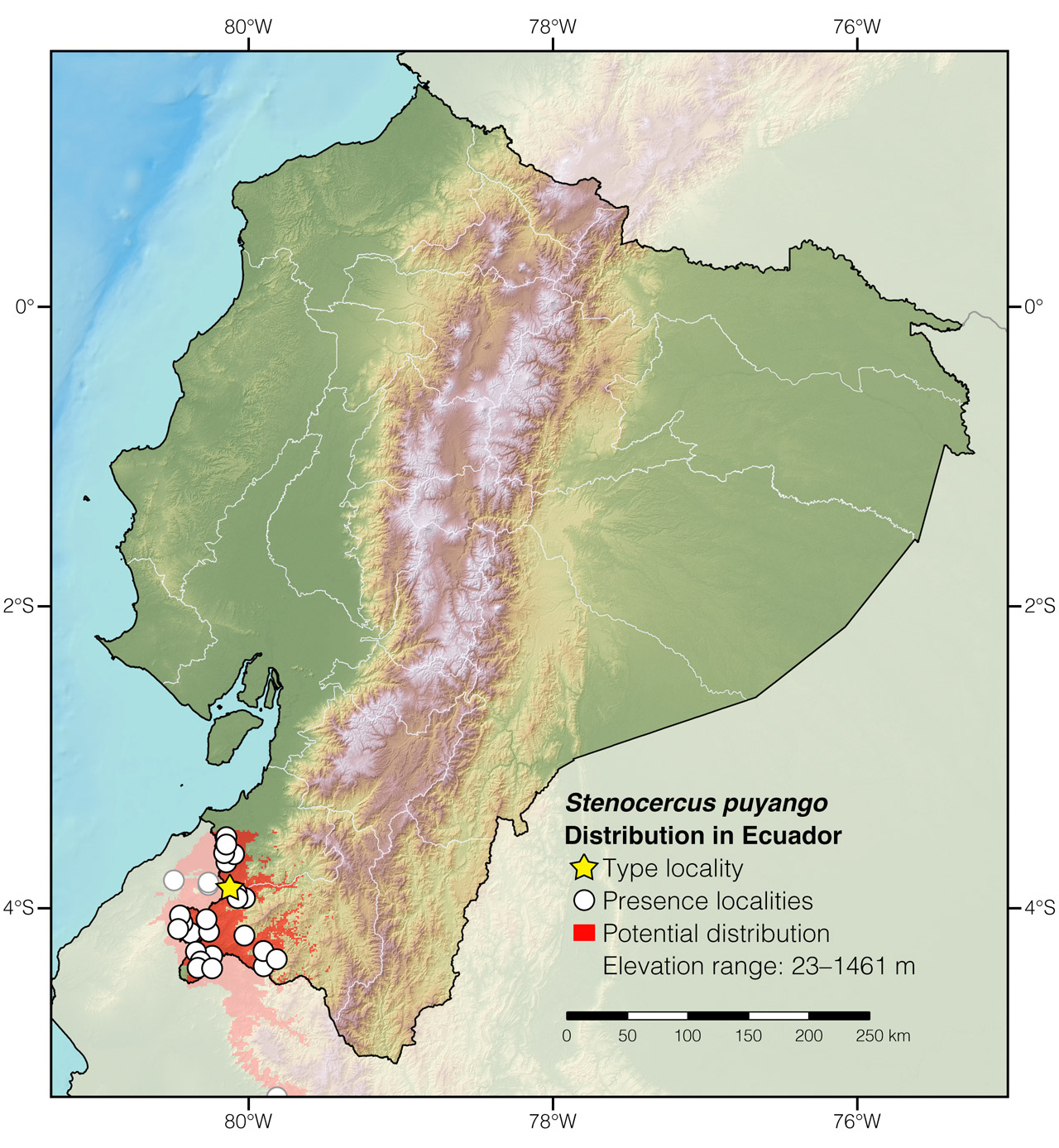

Distribution: Stenocercus puyango is native to the Tumbesian lowlands of extreme southwestern Ecuador (provinces El Oro and Loja) and northwestern Perú (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Distribution of Stenocercus puyango in Ecuador. The star corresponds to the type locality: Bosque Petrificado de Puyango, El Oro province. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The generic name Stenocercus, which comes from the Greek words stenos (=narrow) and kerkos (=tail), refers to the laterally-compressed tail in some members of this genus, which contrasts with the dorsally flattened tail of other Tropiduridae.17 The specific name puyango refers to the type locality: Puyango Petrified Forest.1

See it in the wild: Puyango Whorltail-Iguanas can be seen with almost complete certainty during sunny days in protected areas like the Puyango Petrified Forest and Jorupe Biological Reserve. The easiest way to observe lizards of this species is by walking along forest trails and scanning the microhabitats that the reptiles use to forage and bask.

Author: Amanda QuezadaaAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,bAffiliation: Laboratorio de Herpetología, Universidad del Azuay, Cuenca, Ecuador.

Editor: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

Photographers: Jose VieiraaAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,bAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador. and Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

How to cite? Quezada A (2024) Puyango Whorltail-Iguana (Stenocercus puyango). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/ZIOJ7003

Literature cited:

- Torres-Carvajal O (2005) A new species of iguanian lizard (Stenocercus) from the western lowlands of southern Ecuador and northern Peru. Herpetologica 61: 78–85. DOI: 10.1655/04-32.2

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- Peters JA, Donoso-Barros R (1970) Catalogue of the Neotropical Squamata: part II, lizards and amphisbaenians. Bulletin of the United States National Museum, Washington, D.C., 293 pp.

- Torres-Carvajal O (2007) A taxonomic revision of South American Stenocercus (Squamata: iguania) lizards. Herpetological Monographs 21: 76–178. DOI: 10.1655/06-001.1

- Boulenger GA (1885) Catalogue of the lizards in the British Museum. Taylor & Francis, London, 497 pp.

- Yánez-Muñoz MH, Bejarano-Muñoz P, Sánchez-Nivicela JC (2019) Anfibios y reptiles del páramo al manglar. Capítulo II. In: Garzón-Santomaro C, Sánchez-Nivicela JC, Mena-Valenzuela P, González-Romero D, Mena-Jaén JL (Eds) Anfibios, reptiles y aves de la provincia de El Oro. GADPEO–INABIO, Quito, 45–86.

- Guzmán-Caldas A (2016) Repartición de recursos entre Stenocercus puyango (Torres-Carvajal, 2005) y Microlophus occipitalis (Peters, 1871) (Sauria: Tropiduridae) en el Parque Nacional Cerros de Amotape, Tumbes, Perú. BSc thesis, Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, 81 pp.

- Dávila M, Cisneros-Heredia DF (2017) Use of human-made buildings by Stenocercus lizards (Iguania, Tropiduridae). Herpetology Notes 10: 517–519.

- Venegas P (2005) Herpetofauna del bosque seco ecuatorial de Perú: taxonomía, ecología y biogeografía. Zonas Áridas 9: 9–24. DOI: 10.21704/ZA.V9I1.565

- Armijos Ojeda D, Valarezo K (2010) Diversidad de anfibios y reptiles de un bosque seco en el sur occidente del Ecuador. Ecología Forestal 1: 30–36.

- Acosta Vásconez AN (2014) Diversidad y composición de la comunidad de reptiles del Bosque Protector Puyango. BSc thesis, Universidad San Francisco de Quito, 157 pp.

- Photo by Jorge Castillo.

- Orihuela-Torres A, Ordóñez-Delgado L, Verdezoto-Celi A, Brito J (2018) Diet of the Spectacled Owl (Pulsatrix perspicillata) in Zapotillo, southwestern Ecuador. Revista Brasileira de Ornitologia 26: 52–56. DOI: 10.1007/BF03544415

- Yánez-Muñoz M, Venegas P, Cisneros-Heredia DF, Perez J (2016) Stenocercus puyango. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org. DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T50950699A50950702.en

- Reyes-Puig C (2015) Un método integrativo para evaluar el estado de conservación de las especies y su aplicación a los reptiles del Ecuador. MSc thesis, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador, 73 pp.

- MAE (2012) Línea base de deforestación del Ecuador continental. Ministerio del Ambiente del Ecuador, Quito, 30 pp.

- Duméril AMC, Bibron G (1837) Erpétologie générale ou Histoire Naturelle complète des Reptiles. Librairie Encyclopédique de Roret, Paris, 571 pp. DOI: 10.5962/bhl.title.45973

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Stenocercus puyango in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used. Asterisk (*) indicates type locality.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Ecuador | El Oro | Alamor, 19 km N of | Torres-Carvajal 2007 |

| Ecuador | El Oro | Bosque Petrificado de Puyango* | Torres-Carvajal 2005 |

| Ecuador | El Oro | Marcabelí | Garzón-Santomaro et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | El Oro | Progreso | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | El Oro | Puyango | Torres-Carvajal 2005 |

| Ecuador | El Oro | Quinta Vacacional El Paraíso | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | El Oro | Reserva Ecológica Arenillas I | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | El Oro | Reserva Ecológica Arenillas II | Garzón-Santomaro et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | El Oro | Reserva Ecológica Arenillas, casa guardaparques | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Loja | Cabeza de Toro | MZUA.RE.0442; examined |

| Ecuador | Loja | Chililique | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Loja | Cruzpamba, 3.3 km W of | MZUTI 4209; examined |

| Ecuador | Loja | Garza Real | Armijos & Valarezo 2010 |

| Ecuador | Loja | Jorupe Biological Reserve | Yánez-Muñoz et al. 2008 |

| Ecuador | Loja | Larama | MZUTI 4207; examined |

| Ecuador | Loja | Mangahurquillo | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Loja | Mangurquillo | Torres-Carvajal 2007 |

| Ecuador | Loja | Mirador Cazaderos | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Loja | Progreso | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Loja | Puyango, 4 km S of | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Loja | Quebrada El Ñioco | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Loja | Reserva La Ceiba | MZUTI 4206; examined |

| Ecuador | Loja | Reserva Mangahurco | Photo by Fausto Siavichay |

| Ecuador | Loja | Río Casanga | Cadle 1991 |

| Ecuador | Loja | Tuda | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Loja | Zapallal | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Loja | Zapotillo | Orihuela-Torres et al. 2018 |

| Perú | Lambayeque | Olmos, 21 km E and 7 km N of | Torres-Carvajal 2005 |

| Perú | Piura | Huarmaca | Venegas 2005 |

| Perú | Piura | Limón de Porcuya | Venegas et al. 2013 |

| Perú | Piura | Overal | Venegas et al. 2013 |

| Perú | Piura | Serran | Venegas 2005 |

| Perú | Tumbes | Cerros de Amotape National Park | Guzmán Caldas 2016 |

| Perú | Tumbes | Quebrada Faical | Torres-Carvajal 2005 |

| Perú | Tumbes | Rica Playa | Torres-Carvajal 2005 |