Published February 12, 2022. Updated January 27, 2024. Open access. | Purchase book ❯ |

Angular Whorltail-Iguana (Stenocercus angulifer)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Sauria | Tropiduridae | Stenocercus angulifer

English common name: Angular Whorltail-Iguana.

Spanish common names: Guagsa cornuda angular, guagsa cornuda de Pastaza.

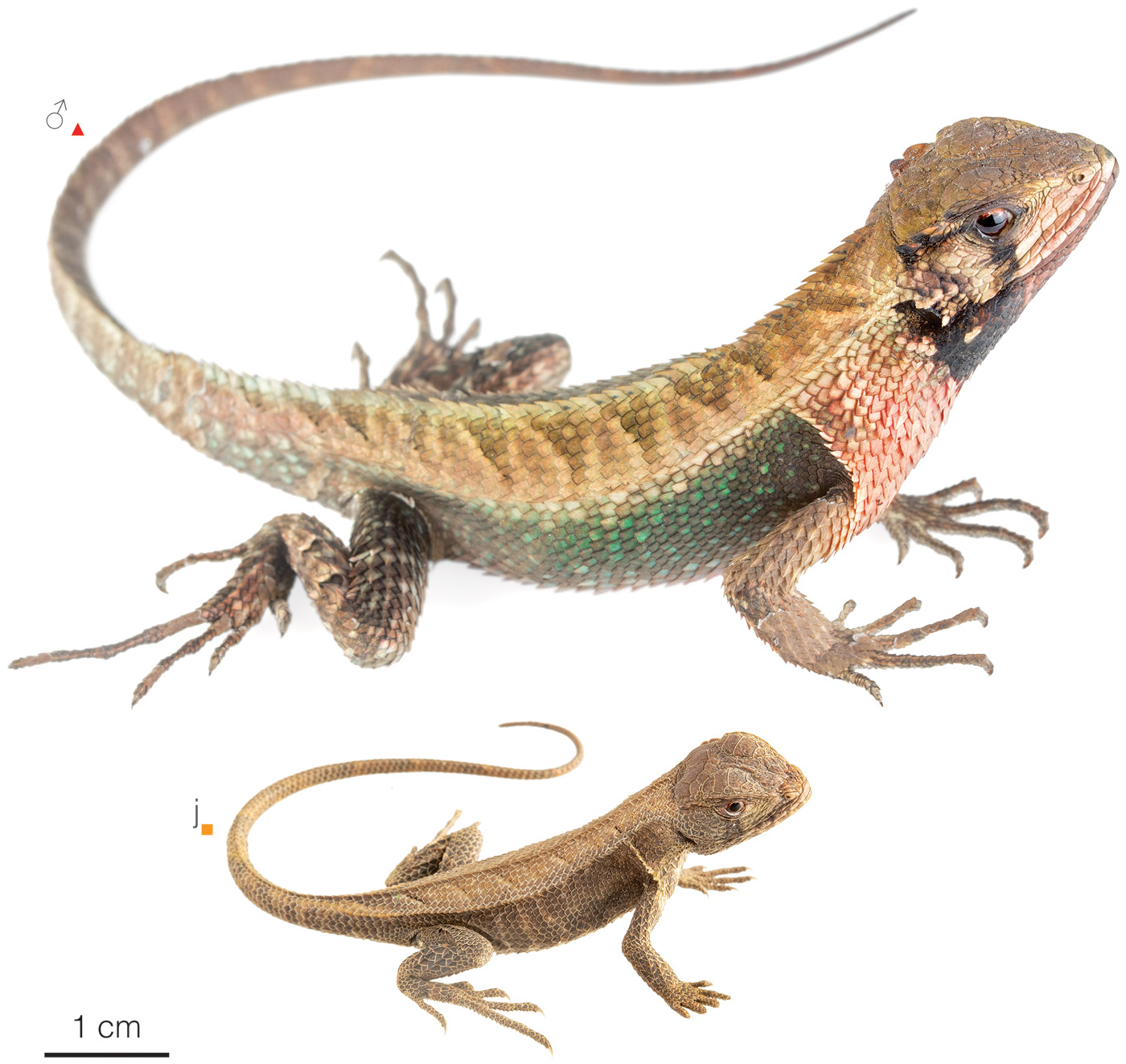

Recognition: ♂♂ 28.8 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=9.6 cm. ♀♀ 24.6 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=8.2 cm..1 The Angular Whorltail-Iguana (Stenocercus angulifer) differs from other lizards in its area of distribution by having keeled overlapping dorsal scales with pointed ends.2 This species is not known to co-occur with other member of its genus. Its closest relative, S. aculeatus, occurs in extreme southeastern Ecuador.1 Males of S. angulifer are larger, more robust, and more brightly colored than females. They also have a raised mid-dorsal crest and enlarged horn-like scales on the parietal region (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Individuals of Stenocercus angulifer from Pastaza province, Ecuador: Río Pastaza (); Tzarentza (). j=juvenile.

Natural history: Stenocercus angulifer is a rarely seen diurnal lizard that inhabits relatively open environments (such as rocky slopes, forest borders, or river edges) in the evergreen foothill forest ecosystem.3 Angular Whorltail-Iguanas are only active during strongly sunny days. Individuals are usually seen basking on rocks or foraging at ground level at the edge of rivers or streams.4 They also have been seen foraging on rock walls or basking on tree-trunks in forest clearings.4 At night and during cloudy days, Angular Whorltail-Iguanas remain hidden in crevices.4 When threatened, these lizards run up or down tree-trunks away from the threat or retreat in holes and crevices.4 If captured, they may shed the tail and bite as a method of defense and escape. Females lay two eggs per clutch.1

Conservation: Least Concern Believed to be safe from extinction given current circumstances..5 Stenocercus angulifer is listed in this category because the species is considered to be facing no major immediate extinction threats.5 Currently, its populations appears to be stable, and although it is not a widely-distributed species, it does occur over an area that retains the majority (~81%) of its original forest cover.6 Although, S. angulifer is considered rare, it is found regularly in some localities.5 It also occurs within the limits of Sangay and Llanganates National parks.

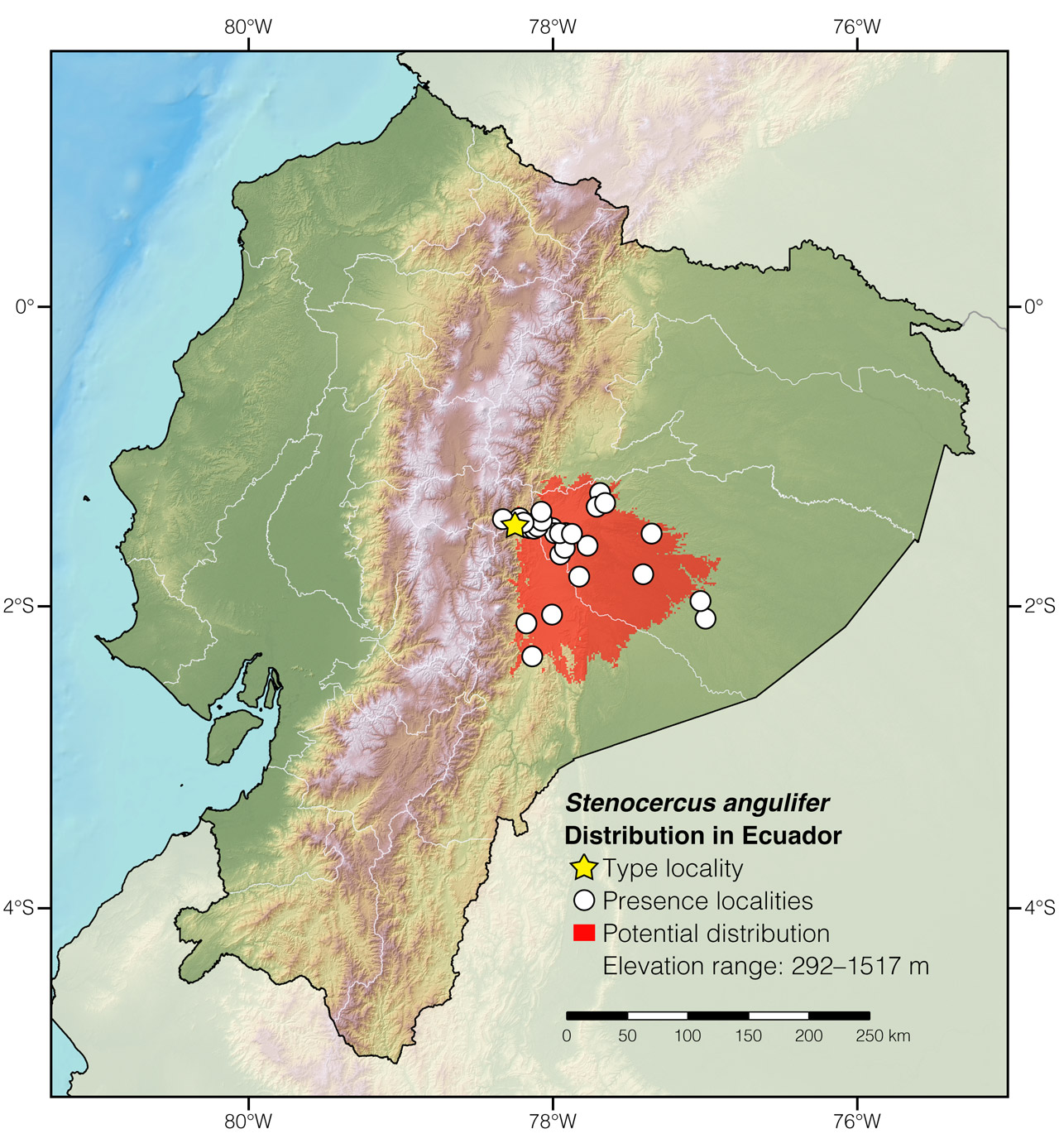

Distribution: Stenocercus angulifer is endemic to an area of approximately 15,853 km2 along the upper Amazon basin and adjacent foothills of the Andes in provinces Morona Santiago, Pastaza, and Tungurahua in Ecuador (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Distribution of Stenocercus angulifer in Ecuador. The star corresponds to the type locality. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The generic name Stenocercus, which comes from the Greek words stenos (=narrow) and kerkos (=tail), refers to the laterally-compressed tail in some members of this genus, which contrasts with the dorsally flattened tail of other Tropiduridae.7 The specific epithet angulifer, which comes from the Latin word angulus (=angle),8 probably refers to the way the dorsal keels form longitudinal lines which converge posteriorly, a characteristic mentioned in the original description of the species.2

See it in the wild: Angular Whorltail-Iguanas are rare and not easily observed in the wild. Even in protected areas like Sangay and Llanganates National Parks, individuals appear to be restricted to the most steep rocky river slopes, which are hard to access. Individuals are seldom seen in closed-canopy forest areas. The easiest way to increase the opportunities of observing lizards of this species is during hot sunny hours along open areas, which is when individuals move and bask in on large stones near rivers and streams.

Author: Amanda QuezadaaAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,bAffiliation: Laboratorio de Herpetología, Universidad del Azuay, Cuenca, Ecuador.

Editor: Alejandro ArteagabAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

Photographer: Jose VieiraaAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,cAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Quezada A (2024) Angular Whorltail-Iguana (Stenocercus angulifer). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/UJOI1892

Literature cited:

- Torres-Carvajal O (2007) A taxonomic revision of South American Stenocercus (Squamata: iguania) lizards. Herpetological Monographs 21: 76–178. DOI: 10.1655/06-001.1

- Werner F (1901) Ueber Reptilien und Batrachier aus Ecuador und Neu-Guinea. Verhandlungen der Kaiserlich-Königlichen Zoologisch-Botanischen Gesellschaft in Wien 51: 593–614. DOI: 10.5962/bhl.part.4586

- Torres-Carvajal O, Pazmiño-Otamendi G, Salazar-Valenzuela D (2019) Reptiles of Ecuador: a resource-rich online portal, with dynamic checklists and photographic guides. Amphibian & Reptile Conservation 13: 209–229.

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- Cisneros-Heredia DF, Reyes-Puig C, Yánez-Muñoz M (2014) Stenocercus angulifer. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org. DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-2.RLTS.T50950618A50950625.en

- MAE (2012) Línea base de deforestación del Ecuador continental. Ministerio del Ambiente del Ecuador, Quito, 30 pp.

- Duméril AMC, Bibron G (1837) Erpétologie générale ou Histoire Naturelle complète des Reptiles. Librairie Encyclopédique de Roret, Paris, 571 pp. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.45973

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington D.C., 882 pp.

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Stenocercus angulifer in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Chiguaza | Torres-Carvajal 2007 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Macas | Torres-Carvajal 2007 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Sardinayacu | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Abitagua | Torres-Carvajal 2007 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Arajuno | Torres-Carvajal 2007 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Arutam Field Station | SMF 91064 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Cabeceras del Río Bobonaza | Torres-Carvajal 2007 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Canelos | Torres-Carvajal 2007 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Estación Científica Amazónica Juri Juri | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Mera | Torres-Carvajal 2007 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Montalvo | Torres-Carvajal 2007 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Palanda | Torres-Carvajal 2007 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Puyo | Torres-Carvajal 2007 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Puyo, 3 km S of | Torres-Carvajal 2007 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Alpayacu | Torres-Carvajal 2007 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Oglán Alto | Torres-Carvajal 2007 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Pindo | This work |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Pucuyacu | Torres-Carvajal 2007 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Villano | Torres-Carvajal 2007 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Santana Research Station | SMF 91065 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Sumak Kawsay | Bentley et al. 2021 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Tinajas del Río Anzu | This work |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Tzarentza | This work |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Veracruz | Torres-Carvajal 2007 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Veracruz, 10 km E of | Torres-Carvajal 2007 |

| Ecuador | Tunguragua | Río Negro | Torres-Carvajal 2007 |

| Ecuador | Tungurahua | El Placer | This work |

| Ecuador | Tungurahua | Pastaza river | This work |