Published February 3, 2021. Updated November 30, 2023. Open access. Peer-reviewed. | Purchase book ❯ |

Pug-nosed Lightbulb-Lizard (Riama simotera)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Sauria | Gymnophthalmidae | Riama simotera

English common names: Pug-nosed Lightbulb-Lizard, O’Shaughnessy’s Lightbulb Lizard.

Spanish common names: Lagartija minadora del frailejón, lagartija bombillo de páramo.

Recognition: ♂♂ 14.9 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=7.5 cm. ♀♀ 14.1 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=7.5 cm.. Lightbulb-lizards are easily distinguishable from other lizards by their fossorial habits and extremities so short that the front and hind limbs cannot reach each other.1,2 Riama simotera is the only member of its genus that inhabits the páramos of northern Ecuador,2 occurring at elevations above any other Ecuadorian lightbulb lizard. Other congeneric lizards that occur near R. simotera are R. raneyi, R. colomaromani, and R. unicolor, but these species have striated or keeled dorsal scales and an incomplete series of superciliary scales.2 Riama simotera has smooth dorsal scales and a complete series of superciliary scales (Fig. 1).2 Adult males differ from females by having broader heads.

Figure 1: Individuals of Riama simotera from El Frailejón, Carchi province, Ecuador. j=juvenile

Natural history: Riama simotera is a rarely seen fossorial lizard especially adapted to life in the páramo (the Andean ecosystem above the continuous forest line). The species also occurs in areas containing a mixture of pastures, crops, rural houses, and remnants of native vegetation. Pug-nosed Lightbulb-Lizards are usually found under rocks, logs, dirt clods, or dead plants in areas dominated by frailejones (shrubs of the genus Espeletia) or terrestrial bromeliads (genus Puya).3–5 Females lay eggs in holes and crevices 5–20 cm under the ground.3 When dug up or otherwise exposed, individuals of R. simotera will quickly flee underground.3 If captured, they may bite or readily shed the tail. Pug-nosed Lightbulb-Lizards are susceptible to high temperatures, dying if exposed to the sun or even if handled for longer than just a few seconds.

Conservation: Endangered Considered to be facing a high risk of extinction in the near future..6,7 Riama simotera meets the IUCN criteria to be listed as Endangered: the species has an extent of occurrence estimated to be around 3,334 km2 (5,378 km2 total minus unsuitable habitat), and available evidence suggests that there is continuing decline in the extent and quality of its habitat due to the expansion of the agricultural frontier6 and wildfires in the páramos.3 Additionally, the species occurs as fragmented populations mostly outside protected areas,4,7 with the exception of El Ángel Ecological Reserve and Bosque Protector Huayrapungo.

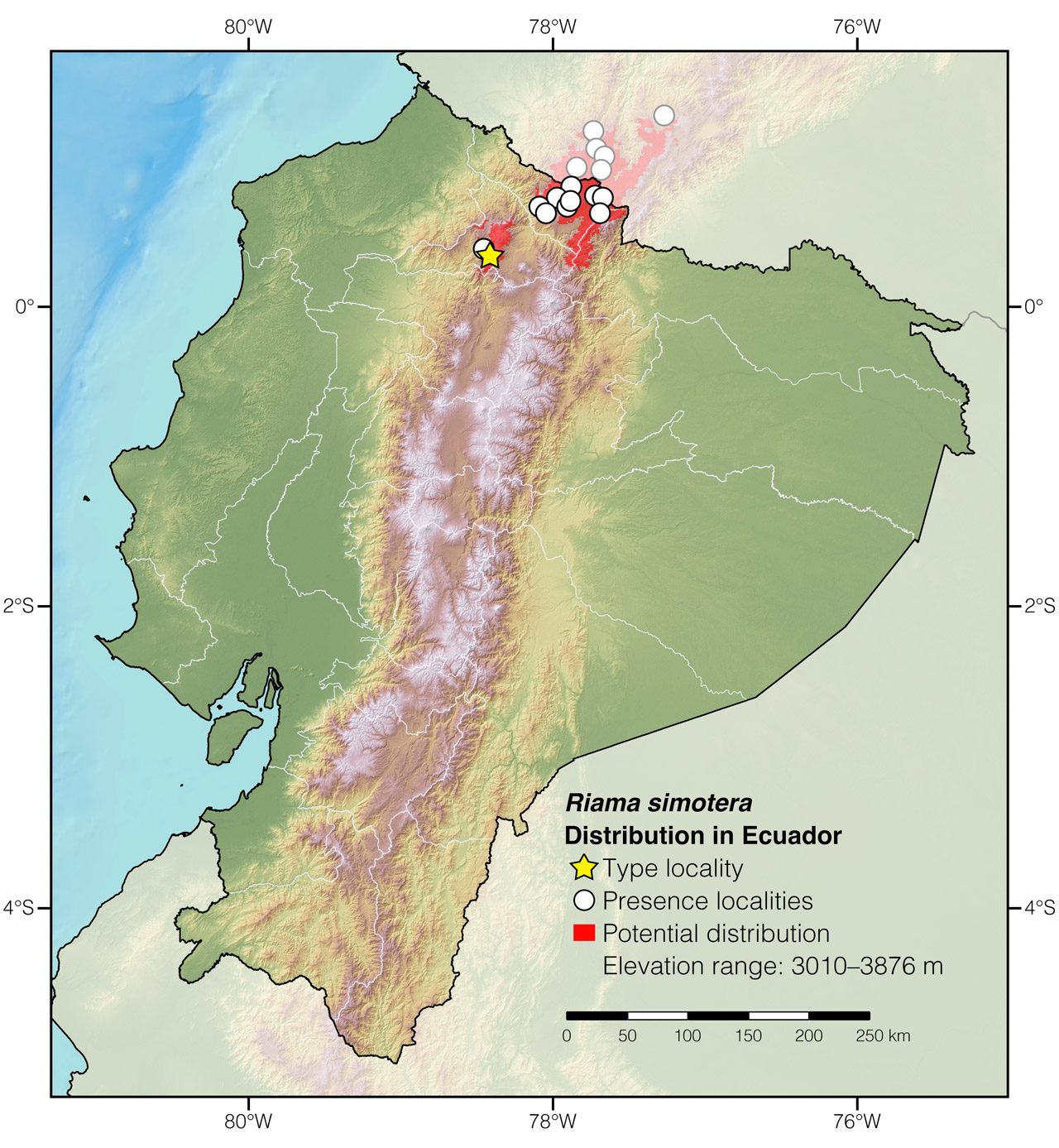

Distribution: Riama simotera is the only Ecuadorian Riama species that is not endemic to the country, as it occurs in Colombia as well.2,5 The species is native to an area of approximately 5,378 km2 in the high Andes of northern Ecuador and southern Colombia (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Distribution of Riama simotera in Ecuador. The star corresponds to the type locality: Intag, Imbabura province. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The generic name Riama does not appear to be a reference to any feature of this group of lizards, but a matter of personal taste. John Edward Gray usually selected girls’ names to use on reptiles.8–11 The specific epithet simotera comes from the Greek simos (=pug-nosed) and the Latin teres (=cylindrical),12 and probably refers to the overall the shape of the lizard.2

See it in the wild: Pug-nosed Lightbulb-Lizards are recorded rarely unless they are actively searched for by digging in areas of soft soil or by turning over rocks in the high páramo ecosystem. Prime locations for finding these shy lizards are El Ángel Ecological Reserve and El Frailejón.

Acknowledgments: Special thanks to Amanda Quezada, Harry Turner, and Frank Pichardo for finding some of the specimens of Riama simotera pictured in this account. Thanks to Frank Pichardo for providing natural history data of R. simotera. Thanks to Amanda Quezada and Andres Perez Salerno for the post-processing of images. This account was published with the support of Secretaría Nacional de Educación Superior Ciencia y Tecnología (programa INEDITA; project: Respuestas a la crisis de biodiversidad: la descripción de especies como herramienta de conservación; No 00110378), Programa de las Naciones Unidas (PNUD), and Universidad San Francisco de Quito (USFQ).

Authors: Miguel Ángel Méndez-GaleanoaAffiliation: Grupo de Biodiversidad y Sistemática Molecular, Instituto de Ciencias Naturales, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá, Colombia. and Alejandro ArteagabAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.

Academic reviewer: Jeffrey D CampercAffiliation: Department of Biology, Francis Marion University, Florence, USA.

Photographer: Jose VieiradAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,eAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Méndez-Galeano MA, Arteaga A (2023) Pug-nosed Lightbulb-Lizard (Riama simotera). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/TOIW7851

Literature cited:

- Doan TM, Castoe TA (2005) Phylogenetic taxonomy of the Cercosaurini (Squamata: Gymnophthalmidae), with new genera for species of Neusticurus and Proctoporus. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 143: 405–416. DOI: 10.1111/j.1096-3642.2005.00145.x

- Kizirian DA (1996) A review of Ecuadorian Proctoporus (Squamata: Gymnophthalmidae) with descriptions of nine new species. Herpetological Monographs 10: 85–155. DOI: 10.2307/1466981

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- Torres-Carvajal O, Pazmiño-Otamendi G, Salazar-Valenzuela D (2019) Reptiles of Ecuador: a resource-rich online portal, with dynamic checklists and photographic guides. Amphibian & Reptile Conservation 13: 209–229.

- Sanchez-Pacheco SJ, Rueda-Almonacid JV, Rada M (2010) Notes on the occurrence of Riama simotera (Squamata, Gymnophthalmidae) in Colombia. Herpetological Bulletin 113: 11–13.

- Cisneros-Heredia DF, Caicedo J (2017) Riama simotera. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org. DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-2.RLTS.T44578813A44578822.en

- Morales-Betancourt MA, Lasso CA, Páez VP, Bock BC (2005) Libro rojo de reptiles de Colombia. Instituto de Investigación de Recursos Biológicos Alexander von Humboldt, Bogotá, 257 pp.

- Gray JE (1831) Description of a new genus of ophisaurean animal, discovered by the late James Hunter in New Holland. Treuttel, Würtz & Co., London, 40 pp.

- Gray JE (1831) A synopsis of the species of the class Reptilia. In: Griffith E, Pidgeon E (Eds) The animal kingdom arranged in conformity with its organization. Whittaker, Treacher, & Co., London, 1–110.

- Gray JE (1838) Catalogue of the slender-tongued saurians, with descriptions of many new genera and species. Annals and Magazine of Natural History 1: 274–283.

- Gray JE (1845) Catalogue of the specimens of lizards in the collection of the British Museum. Trustees of the British Museum, London, 289 pp.

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington D.C., 882 pp.

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Riama simotera in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used. Asterisk (*) indicates type locality.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Colombia | Nariño | Cumbal, 4 km NW of | Sánchez-Pacheco et al. 2012 |

| Colombia | Nariño | Guachucal | Calderon et al. 2023 |

| Colombia | Nariño | Hacienda Alsacia | Sánchez-Pacheco et al. 2012 |

| Colombia | Nariño | Pasto, 8 km NE of | Doan 2003 |

| Colombia | Nariño | Pupiales | Sánchez-Pacheco et al. 2012 |

| Ecuador | Carchi | Bosque Protector Huayrapungo | Suárez Duque 2010 |

| Ecuador | Carchi | Carretera El Ángel–Tulcán | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Carchi | El Ángel, 13 km NE of | Sánchez-Pacheco et al. 2012 |

| Ecuador | Carchi | El Carmelo, 14.6 km NW of | Sánchez-Pacheco et al. 2012 |

| Ecuador | Carchi | El Frailejón | This work; Fig. 1 |

| Ecuador | Carchi | El Frailejón, 4 km S of | Kizirian 1996 |

| Ecuador | Carchi | La Estrellita | Sánchez-Pacheco et al. 2012 |

| Ecuador | Carchi | Palo Blanco | Hernández Gaón 2012 |

| Ecuador | Carchi | Páramo del Infiernillo | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Carchi | Reserva Ecológica El Ángel | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Carchi | Tufiño | Kizirian 1996 |

| Ecuador | Imbabura | Intag, environs of* | O’Shaughnessy 1879 |

| Ecuador | Imbabura | La Delicia | Kizirian 1996 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Laguna Negra | GEOCOL S.A. 2017 |