Published June 4, 2020. Updated November 29, 2023. Open access. Peer-reviewed. | Purchase book ❯ |

Turniptail Lightbulb-Lizard (Riama cashcaensis)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Sauria | Gymnophthalmidae | Riama cashcaensis

English common names: Turniptail Lightbulb-Lizard, Kizirian’s Lightbulb-Lizard.

Spanish common names: Lagartija minadora cola de nabo, lagartija minadora de Cashca Totoras.

Recognition: ♂♂ 14.3 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=6.8 cm. ♀♀ 14.1 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=6.4 cm..1–3 Lightbulb-lizards are easily distinguishable from other lizards by their fossorial habits and extremities so short that the front and hind limbs cannot reach each other.1,2 The Turniptail Lightbulb-Lizard (Riama cashcaensis) is the only member of its genus known from its area of distribution. It is easy to recognize by its stocky body, orangish flanks, and single superciliary scale.1–3 Other fossorial lizards that may occur near R. cashcaensis are R. labionis, a more slender reptile that lacks blotches on the flanks, and Andinosaura crypta, a longer-limbed saurian with light dorsolateral stripes.2 Adult males of R. cashcaensis differ from females by being larger, having broader heads, and bright reddish flanks (Fig. 1).1–3

Figure 1: Individuals of Riama cashcaensis from La Moya, Bolívar province, Ecuador. j=juvenile.

Natural history: Riama cashcaensis is a rarely seen fossorial lizard that inhabits old-growth to heavily disturbed high evergreen montane forests, cloud forests, forest borders, corn fields, pastures, and rural gardens.1–4 It also occurs in areas containing a mixture of pastures, rural houses, and remnants of native vegetation. Lizards of this species spend most of their lives in tunnels they excavate in areas of soft soil or under rocks, logs, and leaf-litter.1–4 Their burrows are often shared by individuals of Pholidobolus prefrontalis.3 The diet in R. cashcaensis includes beetles and their larvae, hemipterans, leafhoppers, ants, moth larvae, and grasshoppers.1–3 When dug up or otherwise exposed, individuals of R. cashcaensis will quickly flee underground. If captured, they may bite or readily shed the tail. Turniptail Lightbulb-Lizards are susceptible to high temperatures, dying if exposed to the sun or even if handled for longer than just a few seconds.3

Conservation: Endangered Considered to be facing a high risk of extinction in the near future..5 Riama cashcaensis is listed in this category because only about 693 km2 of its area of distribution holds remnants of native vegetation. The species occurs as fragmented populations and there is continuing decline in the extent and quality of its habitat,4 mostly from encroaching human activities such as agriculture, cattle grazing, and the replacement of native vegetation with eucalyptus and pine trees.4 Another threat faced by the species is direct killing: Turniptail Lightbulb-Lizards are usually killed on sight by humans alleging precautionary reasons.3 Riama cashcaensis occurs in one protected area: Cashca Totoras Protected Forest.4

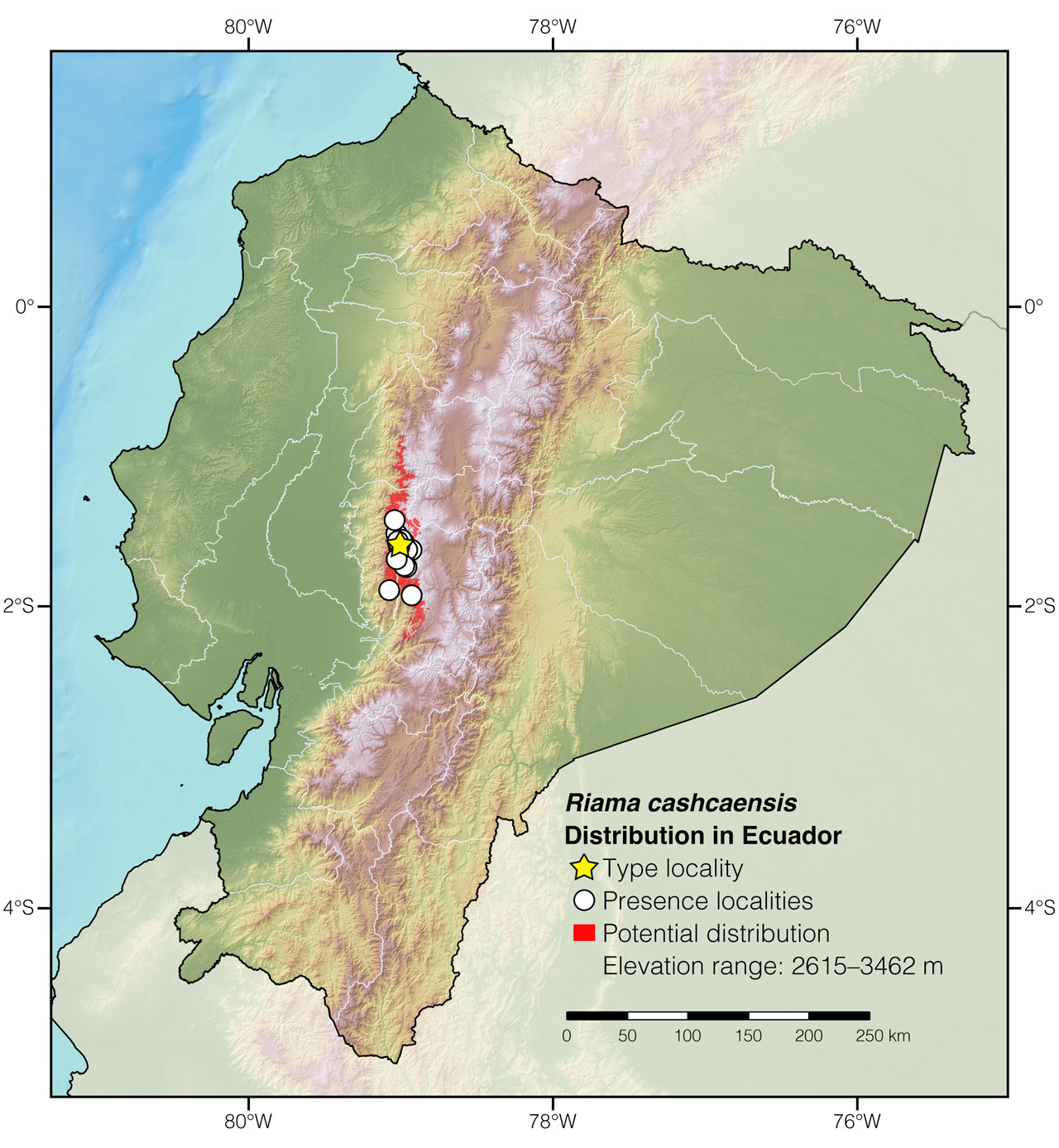

Distribution: Riama cashcaensis is endemic to an area of approximately 1,658 km2 in the western slopes of the Andes in central Ecuador (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Distribution of Riama cashcaensis in Ecuador. The star corresponds to the type locality: Guaranda, Bolívar province. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The generic name Riama does not appear to be a reference to any feature of this group of lizards, but a matter of personal taste. John Edward Gray usually selected girls’ names to use on reptiles.6–9 The specific epithet cashcaensis is an adjective derived from the Quechua word cashca, a species of tree of the genus Weinmannia that occurs in the habitat of R. cashcaensis.1

See it in the wild: Turniptail Lightbulb-Lizards are recorded rarely unless they are actively searched for by turning over boulders and rotten logs in areas with adequate forest cover. They are particularly abundant along the border between agricultural fields and remnants of native forest in the outskirts of cities and towns such as Guaranda, Guanujo, and Salinas.

Special thanks to James Baker for symbolically adopting the Turniptail Lightbulb-Lizard and helping bring the Reptiles of Ecuador book project to life.

Click here to adopt a species.

Acknowledgments: Special thanks to Eric Osterman and Grace Reyes for finding some of the individuals of Riama cashcaensis pictured here.

Author and photographer: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

Academic reviewer: Jeffrey D CamperbAffiliation: Department of Biology, Francis Marion University, Florence, USA.

How to cite? Arteaga A (2023) Turniptail Lightbulb-Lizard (Riama cashcaensis). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/QNPH8146

Literature cited:

- Kizirian DA, Coloma LA (1991) A new species of Proctoporus (Squamata: Gymnophthalmidae) from Ecuador. Herpetologica 47: 420–429.

- Kizirian DA (1996) A review of Ecuadorian Proctoporus (Squamata: Gymnophthalmidae) with descriptions of nine new species. Herpetological Monographs 10: 85–155. DOI: 10.2307/1466981

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- Lewis TR (2002) Threats facing endemic herpetofauna in the cloud forest reserves of Ecuador. Herpetological Bulletin 79: 18–26. DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.3744655

- Cisneros-Heredia DF, Yánez-Muñoz M, Brito J (2019) Riama cashcaensis. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org. DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-3.RLTS.T50950469A50950478.en

- Gray JE (1831) Description of a new genus of ophisaurean animal, discovered by the late James Hunter in New Holland. Treuttel, Würtz & Co., London, 40 pp.

- Gray JE (1831) A synopsis of the species of the class Reptilia. In: Griffith E, Pidgeon E (Eds) The animal kingdom arranged in conformity with its organization. Whittaker, Treacher, & Co., London, 1–110.

- Gray JE (1838) Catalogue of the slender-tongued saurians, with descriptions of many new genera and species. Annals and Magazine of Natural History 1: 274–283.

- Gray JE (1845) Catalogue of the specimens of lizards in the collection of the British Museum. Trustees of the British Museum, London, 289 pp.

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Riama cashcaensis in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used. Asterisk (*) indicates type locality.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Ecuador | Bolívar | Guanujo, 4 km E of | Arredondo & Sánchez-Pacheco 2010 |

| Ecuador | Bolívar | Guaranda, 14.1 km E of | Kizirian & Coloma 1991 |

| Ecuador | Bolívar | Guaranda, 9.4 km E of | Doan 2003 |

| Ecuador | Bolívar | Guaranda* | Kizirian & Coloma 1991 |

| Ecuador | Bolívar | La Moya | This work; Fig. 1 |

| Ecuador | Bolívar | Las Cochas | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Bolívar | Río Tatahuazo | Kizirian & Coloma 1991 |

| Ecuador | Bolívar | Road to Santa Rosa de Totoras | Kizirian & Coloma 1991 |

| Ecuador | Bolívar | Salinas de Guaranda | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Bolívar | Salinas, 30 km S of | Kizirian & Coloma 1991 |

| Ecuador | Bolívar | San Pablo–Chillanes | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Bolívar | Vía a Guanujo | Kizirian & Coloma 1991 |

| Ecuador | Chimborazo | Cajabamba, 35 km SE of | Sánchez-Pacheco et al. 2012 |