Published May 3, 2022. Updated October 29, 2023. Open access. | Purchase book ❯ |

Long-nosed Wood-Turtle (Rhinoclemmys nasuta)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Testudines | Geoemydidae | Rhinoclemmys nasuta

English common names: Long-nosed Wood-Turtle, Large-nosed Wood-Turtle, Chocoan River Turtle.

Spanish common names: Sabalatera, sabaleta, zabeletera (Ecuador); tortuga de río chocoana, sabalatera, tortuga blanca, hicotea blanca (Colombia).

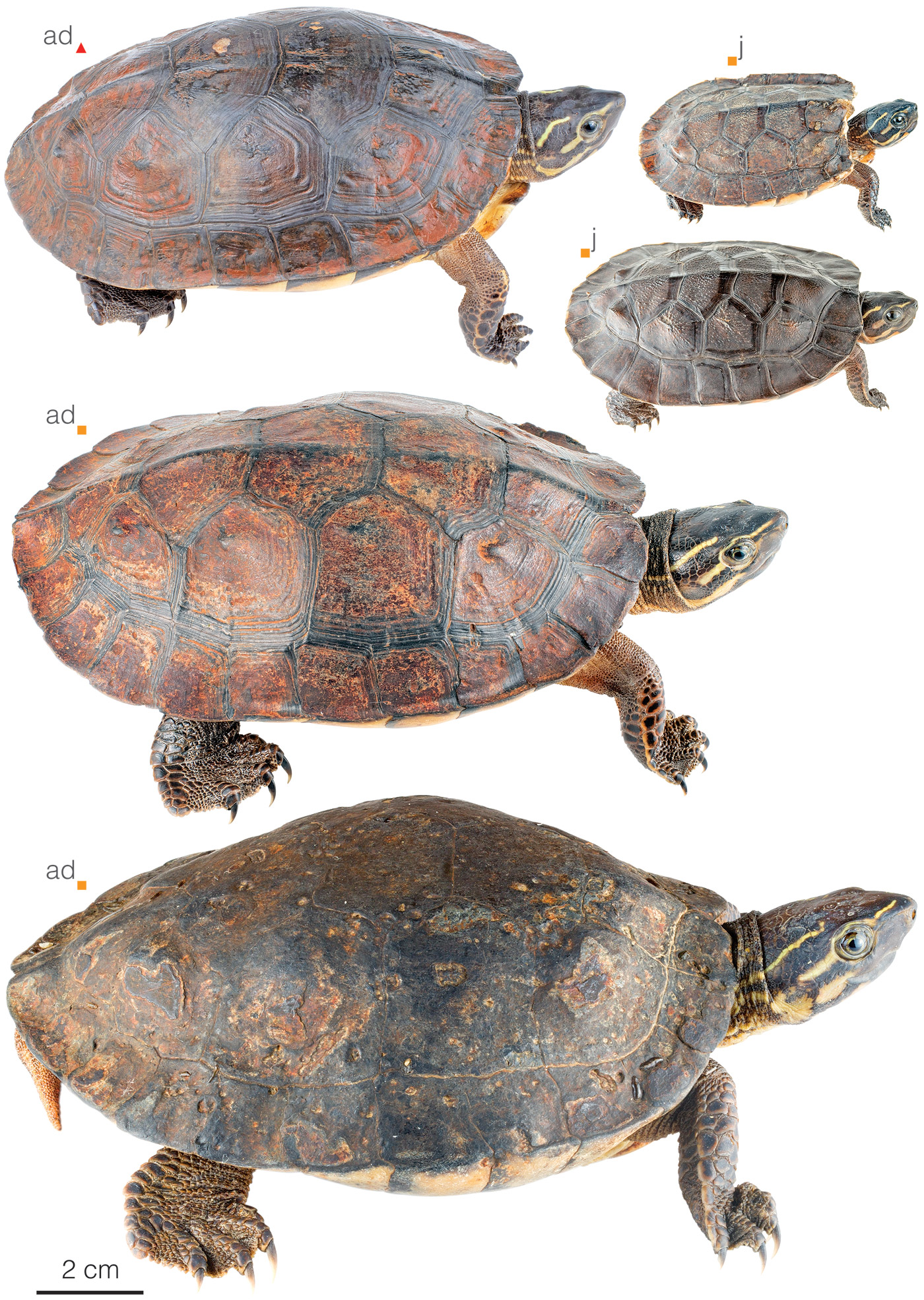

Recognition: ♂♂ 19.6 cmMaximum straight length of the carapace. ♀♀ 22.9 cmMaximum straight length of the carapace..1–3 The Long-nosed Wood-Turtle (Rhinoclemmys nasuta) can be identified from other Chocoan freshwater turtles mainly on the basis of coloration. The head is dark brown with a series of pale yellow longitudinal lines: one running from the top of the snout, over the orbit, to the cheek; another one on the parietal region; and a third one along the chin.2–5 The carapace is ovoid and has a deep chocolate brown coloration.5,6 The plastron is cream or pale yellow with a large black blotch on each plate.4,6 Rhinoclemmys nasuta can be separated from R. annulata and R. melanosterna by having a flattened (rather than domed) carapace, a prominent snout, yellowish brown iris, and an cryptic, rather than ornate yellow, skin coloration.5,6 Males of R. nasuta are smaller, have a more concave plastron, and a longer tail than females.2,7,8

Figure 1: Individuals of Rhinoclemmys nasuta from Durango () and Canandé Reserve (), Esmeraldas province, Ecuador. j=juvenile.

Natural history: RareTotal average number of reported observations per locality less than ten. (up to 4.6 individuals per hectare9) in Ecuador,10 but commonRecorded weekly in densities above five individuals per locality. (up to 1,560 individuals per hectare) in some areas of Colombia.2 Rhinoclemmys nasuta is a primarily aquatic turtle that inhabits bodies of water in evergreen lowland forests. Long-nosed Wood-Turtles are the most aquatic of the Rhinoclemmys genus, spending almost the entirety of their life in large rivers, streams, ponds, lagoons, and swamps.2,7 However, individuals occasionally dwell on the forest floor and may enter brackish water7 as well as inhabit temporary water bodies.2 The home range size of in this species is small. In a locality in Colombia, males of this species spent 80% of the time within a 17 m radius; females spent 70% of the time within a 3 m radius.3 However, males moved up to 120 m along a stream.3 Long-nosed Wood-Turtles are active during the day or at night, with an activity peak at 6:00–8:00 pm and 8:00–9:00 am.3 When not active, they sleep while floating still on shallow water10 or they may hide in caves, under dense leaf-litter, logs,9 or retreat in underwater shelters formed by roots of riparian vegetation.2

Long-nosed Wood-Turtles are mainly herbivorous,9 feeding on aquatic plants, leaves, seeds, and fruits.2 Occasionally, they may consume small insects, spiders, frog eggs, and carrion.2,7,9 There are records of crocodilians (Crocodylus acutus and Caiman fuscus), snakes (Drymarchon melanurus), and marsupials preying upon individuals of this species.2,7 Parasites of Rhinoclemmys nasuta include nematodes, trematodes, ticks, and leeches.2 The breeding season occurs throughout the year2,7 and is closely correlated with precipitation.11 Females deposit 1–2 (usually only one) eggs that weigh 41–62 g and measure 6.2–7.5 cm long and 3.1–3.9 cm wide.7,11 These are not laid inside nests, but simple on depressions in the ground.2 The females sometimes cover them with leaf-litter,7 but no additional care is provided to the clutch.2 The incubation period is 133–135 days (about 4.4. months) and the hatchlings measure 5.6–6.1 cm in carapace length.11 The lifespan for wild turtles of this species has been estimated to be at least 27.4 years.3 In captivity, one individual lived for 19 years.2

Conservation: Near Threatened Not currently at risk of extinction, but requires some level of management to maintain healthy populations..12,13 Rhinoclemmys nasuta is listed in this category given its wide distribution over areas that have not been heavily affected by deforestation, including the entire Colombian Pacific coast and major national parks in Ecuador: Awá Ethnic and Forest Reserve, Cotacachi Cayapas Ecological Reserve, and Cayapas Mataje Ecological Reserve. Therefore, the species is considered to be facing no major immediate extinction threats. Although some isolated populations in Colombia are stable,8 those outside protected areas in Ecuador and some parts of Colombia are declining due to habitat loss and indiscriminate harvesting.2,8,12 Adult turtles are hunted for medicinal use, carving of ornaments, consumption, or to be sold as pets.8,14 These threats, in combination with the species’ natural low fecundity,2 may result in R. nasuta being included in a threatened category in the future.2

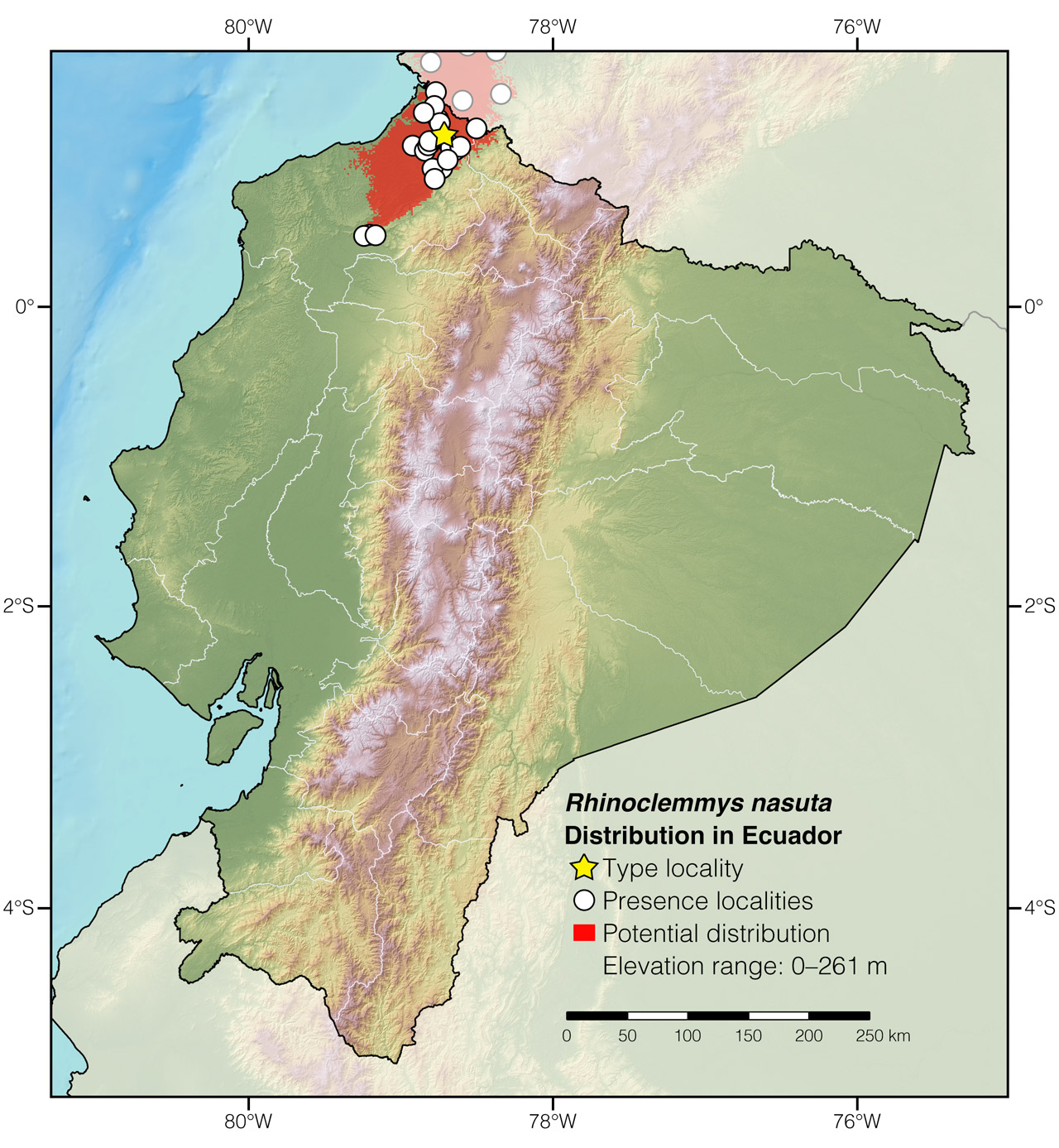

Distribution: Rhinoclemmys nasuta is native to an estimated 84,784 km2 area in the Chocó biogeographic region, from northwestern Colombia to extreme northwestern Ecuador.1,5 In Ecuador, R. nasuta has been recorded at elevations between 0 and 261 m (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Distribution of Rhinoclemmys nasuta in Ecuador. The star corresponds to the type locality: Pulún, Esmeraldas province. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The generic name Rhinoclemmys, which comes from the Greek words rhinos (meaning “nose”) and klemmys (meaning “tortoise”),15 refers to the protuberant snout of some species of the genus.16 The specific epithet nasuta is a Latin word meaning “large-nosed.”15

See it in the wild: Long-nosed Wood-Turtles are rarely encountered in the wild in Ecuador. Most recent observations come from towns along the Santiago river, or in forested areas along tributaries of the Canandé and Bogotá rivers. In these areas, the turtles are most easily found by walking along slow-moving rivers, medium-sized streams, and ponds right after sunset or by setting up pitfall traps with fruit bait in marshy areas.

Special thanks to David Smith for symbolically adopting the Long-nosed Wood-Turtle and helping bring the Reptiles of Ecuador book project to life.

Click here to adopt a species.

Author: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

Photographer: Jose VieirabAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,cAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Arteaga A (2022) Long-nosed Wood-Turtle (Rhinoclemmys nasuta). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/IDGS1450

Literature cited:

- Rhodin AGJ, Iverson JB, Bour R, Fritz U, Georges A, Shaffer HB, van Dijk PP (2021) Turtles of the world: annotated checklist and atlas of taxonomy, synonymy, distribution, and conservation status. Chelonian Research Monographs 8: 1–472. DOI: 10.3854/crm.8.checklist.atlas.v9.2021

- Carr JL, Giraldo A, Garcés-Restrepo MF (2012) Rhinoclemmys nasuta. In: Páez VP, Morales-Betancourt MA, Lasso CA, Castaño-Mora OV, Bock BC (Eds) Biología y conservación de las tortugas continentales de Colombia. Serie Editorial Recursos Hidrobiológicos y Pesqueros Continentales de Colombia, Instituto de Investigación de Recursos Biológicos Alexander von Humboldt (IAvH), Bogotá, 314–322.

- Pérez JV (2007) Tasa de crecimiento y rango habitacional de Rhinoclemmys nasuta en isla Palma, Pacífico colombiano. BSc thesis, Universidad del Valle, 40 pp.

- Carr JL, Almendáriz A (1989) Contribución al conocimiento de la distribución geográfica de los quelonios del Ecuador occidental. Revista Politécnica 14: 75–103.

- Rueda-Almonacid JV, Carr JL, Mittermeier RA, Rodríguez-Mahecha JV, Mast RB, Vogt RC, Rhodin AGJ, de la Ossa-Velásquez J, Rueda JN, Mittermeier CG (2007) Las tortugas y los cocodrilianos de los países andinos del trópico. Conservación Internacional, Bogotá, 538 pp.

- MECN (2010) Serie herpetofauna del Ecuador: El Chocó esmeraldeño. Museo Ecuatoriano de Ciencias Naturales, Quito, 232 pp.

- Medem F (1962) La distribución geográfica y ecología de los Crocodylia y Testudinata en el Departamento del Chocó. Revista de la Academia Colombiana de Ciencias Exactas, Físicas, y Naturales 11: 279–303.

- Carr JL, Giraldo A, Garcés-Restrepo MF (2017) Rhinoclemmys nasuta (Boulenger 1902) Tortuga de río chocoana, sabaletera. Catálogo de Anfibios y Reptiles de Colombia 3: 43–49.

- Calero Herrera WA (2015) Densidad, estructura poblacional y dieta de Rhinoclemmys nasuta (Testudines: Cryptodira) en la reserva Río Canandé, Noroccidente Ecuatoriano. BSc thesis, Quito, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador, 82 pp.

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- Garcés-Restrepo MF, Rivera-Domínguez N, Giraldo A, Carr JL (2017) Reproductive aspects of the Chocoan River Turtle (Rhinoclemmys nasuta, Geoemydidae) along the Colombian Pacific coast. Amphibia-Reptilia 38: 351–361. DOI: 10.1163/15685381-00003115

- Tortoise & Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group (1996) Rhinoclemmys nasuta. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org. DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.1996.RLTS.T19505A8944337.en

- Morales-Betancourt MA, Lasso CA, Páez VP, Bock BC (2005) Libro rojo de reptiles de Colombia. Instituto de Investigación de Recursos Biológicos Alexander von Humboldt, Bogotá, 257 pp.

- Carr JL, Almendáriz A, Simmons JE, Nielsen MT (2014) Subsistence hunting for turtles in northwestern Ecuador. Acta Biológica Colombiana 19: 401–413. DOI: 10.15446/abc.v19n3.42886

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington D.C., 882 pp.

- Ernst C (1981) Rhinoclemmys Fitzinger, Neotropical forest terrapins. Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles 274: 1–2.

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Rhinoclemmys nasuta in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used. Asterisk (*) indicates type locality.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Colombia | Nariño | Playa del Mira | Carr et al. 2012 |

| Colombia | Nariño | Río Curay | ICN 7750 |

| Colombia | Nariño | Río Güiza | Carr et al. 2012 |

| Colombia | Nariño | Río Panambi | Carr et al. 2012 |

| Colombia | Nariño | Río Patía | Carr et al. 2012 |

| Colombia | Nariño | Tumaco | Carr et al. 2012 |

| Ecuador | Carchi | Tobar Donoso | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Bosque Protector La Chiquita | Carr & Almendáriz 1990 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Casa del Medio | This work |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Cómo hacemos | Carr & Almendáriz 1990 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Concepción | Carr et al. 2014 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Durango | This work |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Estero El Ceibo | Carr & Almendáriz 1990 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Estero El Placer | Carr & Almendáriz 1990 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Guembi | Carr & Almendáriz 1990 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | La Boca | Carr & Almendáriz 1990 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Nueva Esperanza | Carr et al. 2014 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Pulún* | Boulenger 1902 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Quebrada Chiquita | Carr & Almendáriz 1990 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Río Achiote | This work |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Río Durango | GBIF |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Río Tulubí | Ítalo Tapia, pers. comm. |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Salto del Bravo, 2 km N of | Carr & Almendáriz 1990 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | San José de Cachabí | Carr & Almendáriz 1990 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | San Lorenzo | Carr & Almendáriz 1990 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Sarria | Carr & Almendáriz 1990 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Tributary of the Río Canandé | Calero Herrera 2015 |