Published October 10, 2019. Updated May 29, 2024. Open access. Peer-reviewed.

Pinzón Island Racer (Pseudalsophis slevini)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Serpentes | Colubridae | Pseudalsophis slevini

English common name: Pinzón Island Racer.

Spanish common names: Culebra corredora de Pinzón, culebra corredora de Slevin.

Recognition: ♂♂ 52.6 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=37.5 cm. ♀♀ 50.7 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=35.8 cm..1 Pseudalsophis slevini is the only snake known to occur on Pinzón Island, and is one of two species of snakes in Galápagos having a black banded pattern (Fig. 1).1,2 The background color of the dorsal surfaces is golden yellow or pale yellowish gray with a brownish olive head cap and a faint dark brown postocular streak.3,4 The only other banded snake in Galápagos is P. darwini, which is endemic to Isabela and Fernandina islands.1,2

Figure 1: Individuals of Pseudalsophis slevini from Bahía Pinzón, Pinzón Island, Galápagos, Ecuador.

Natural history: Pseudalsophis slevini is a diurnal snake that inhabits the coastal volcanic rock areas, seasonally dry forests, and grasslands of Pinzón Island.2,3 Pinzón Island Racers are active throughout the day, but usually not during hot midday hours. Their activity occurs primarily at ground level on bare soil, lava blocks, and leaf-litter, but semi-arboreal foraging on branches has also been observed.2 Snakes of this species are mildly venomous, which means they are dangerous to small prey, but not to humans.4 They are foraging predators and their diet includes geckos (Phyllodactylus duncanensis), lizards (Microlophus duncanensis), smaller snakes of the same species, and insects.3,5,6 There are recorded instances of predation on members of this species by hawks.7

Conservation: Vulnerable Considered to be facing a high risk of extinction in the mid-term future..8 Pseudalsophis slevini is listed in this category because the species is restricted to an island of only 18 km2 and, therefore, is susceptible to extreme population fluctuations caused by random climatic or biological (for example, invasive species) events. Rats invaded Pinzón Island for nearly 200 years,9 depleting the population of snakes by preying on its eggs and juveniles. Thanks to efforts led by the Galápagos National Park, rats were finally eradicated from the island in 2012.2

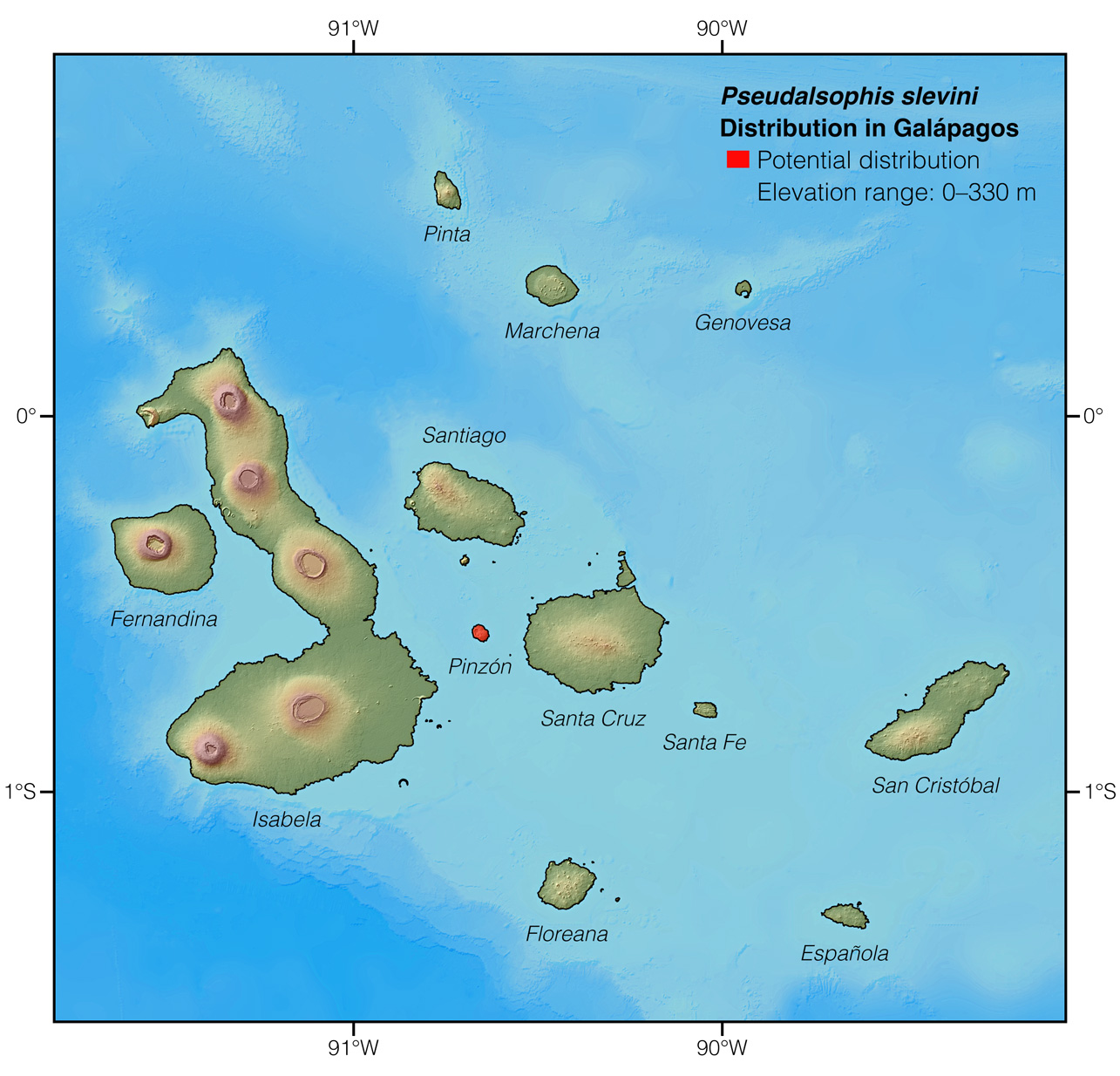

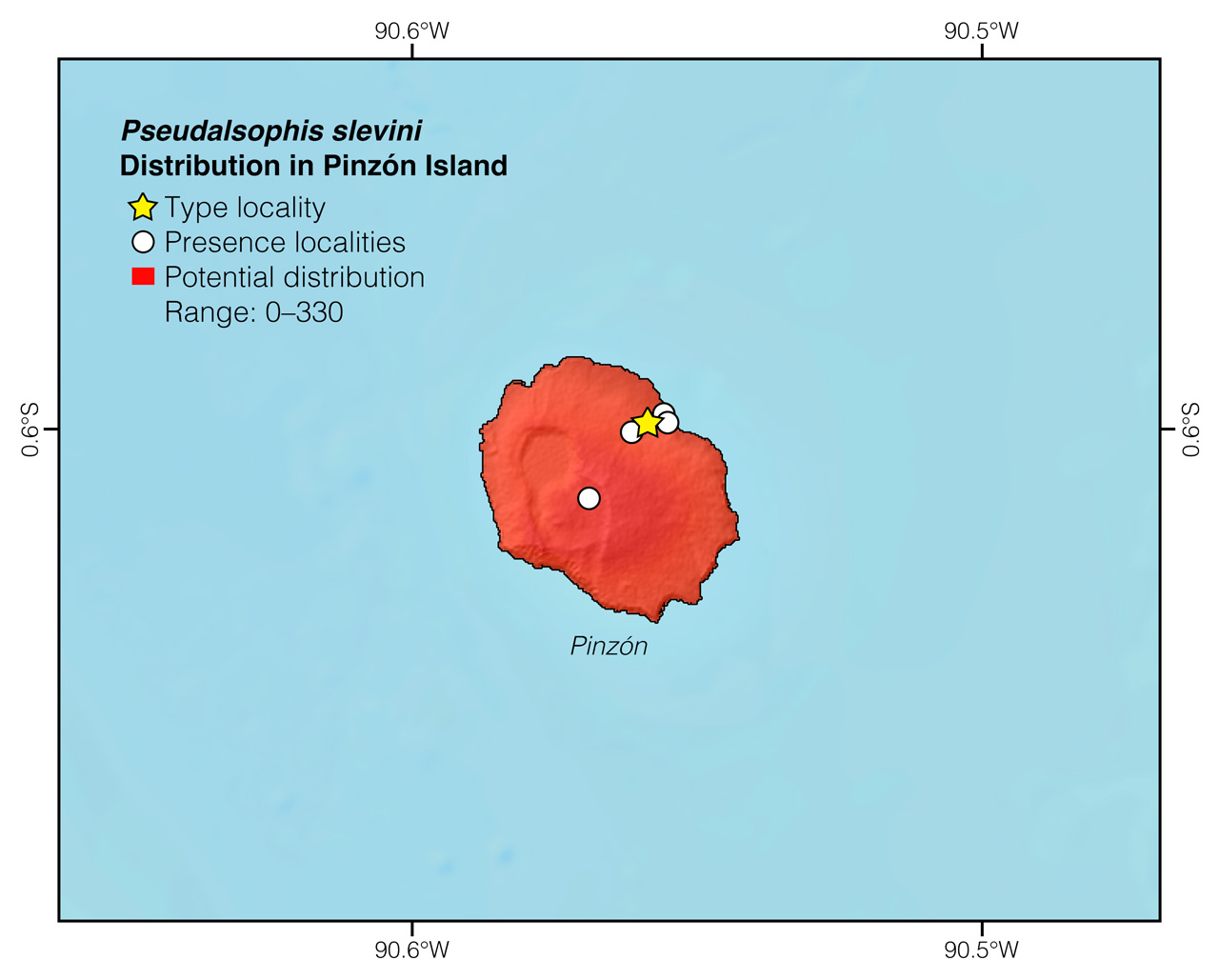

Distribution: Pseudalsophis slevini is endemic to Pinzón, an 18 km2 island in central Galápagos, Ecuador (Figs 2, 3).

Figure 2: Distribution of Pseudalsophis slevini in Galápagos. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Figure 3: Distribution of Pseudalsophis slevini in Pinzón Island. The star corresponds to the type locality: NE slope of Isla Pinzón. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The generic name Pseudalsophis comes from the Greek words pseudo (=false) and Alsophis (a genus of Caribbean snakes), referring to the similarity between snakes of the two genera.1 The specific epithet slevini honors Joseph Richard Slevin (1881–1957), an American scientist that worked as the curator of herpetology at the California Academy of Sciences (CAS) and was part of the research expedition conducted by this institution to the Galápagos Islands in 1905–1906. Slevin collected the holotype of the species.4 During the CAS expedition, nearly 4,000 reptiles were collected.3

See it in the wild: Racer snakes can be seen almost daily at Pinzón Island, especially during sunny mornings along the main trail leading to the crater. However, access to the island is restricted by the Galápagos National Park.

Special thanks to Ron Smith for symbolically adopting the Pinzón Island Racer and helping bring the Reptiles of Ecuador book project to life.

Click here to adopt a species.

Authors: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador. and Juan M GuayasaminbAffiliation: Universidad San Francisco de Quito, Quito, Ecuador.

Academic reviewers: Robert A ThomascAffiliation: Loyola University, New Orleans, United States. and Luis Ortiz-CatedraldAffiliation: Massey University, Palmerston North, New Zealand.

Photographer: Jose VieiraeAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,fAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Arteaga A, Guayasamin JM (2024) Pinzón Island Racer (Pseudalsophis slevini). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/HINU7350

Literature cited:

- Zaher H, Yánez-Muñoz MH, Rodrigues MT, Graboski R, Machado FA, Altamirano-Benavides M, Bonatto SL, Grazziotin FG (2018) Origin and hidden diversity within the poorly known Galápagos snake radiation (Serpentes: Dipsadidae). Systematics and Biodiversity 16: 614–642. DOI: 10.1080/14772000.2018.1478910

- Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J, Tapia W, Guayasamin JM (2019) Reptiles of the Galápagos: life on the Enchanted Islands. Tropical Herping, Quito, 208 pp. DOI: 10.47051/AQJU7348

- Van Denburgh J (1912) Expedition of the California Academy of Sciences to the Galápagos Islands, 1905-1906. IV. The snakes of the Galápagos Islands. Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences 1: 323–374.

- Thomas RA (1997) Galápagos terrestrial snakes: biogeography and systematics. Herpetological Natural History 5: 19–40.

- Ortiz-Catedral L, Christian E, Skirrow MJA, Rueda D, Sevilla C, Kumar K, Reyes EMR, Daltry JC (2019) Diet of six species of Galapagos terrestrial snakes (Pseudalsophis spp.) inferred from faecal samples. Herpetology Notes 12: 701–704.

- Cisneros-Heredia DF, Reyes-Puig C (2023) Natural history and conservation of the Galápagos snake radiation. In: Lillywhite HB, Martins M (Eds) Islands and snakes. Oxford University Press, 158–182. DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780197641521.003.0009

- Wood GC (1939) Zoological results of the George Vanderbilt South Pacific Expedition of 1937. Part IV. Galápagos reptiles. Notulae Naturae 16: 1–2.

- Márquez C, Cisneros-Heredia DF (2019) Pseudalsophis slevini. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org. DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-3.RLTS.T190543A54447674.en

- Clark DA (1981) Foraging patterns of black rats across a desert-montane forest gradient in the Galápagos Islands. Biotropica 13: 182–194.

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Pseudalsophis slevini in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used. Asterisk (*) indicates type locality.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Bahía Pinzón | Arteaga et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | El Estadio | Arteaga et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | NE slope of Isla Pinzón* | Van Denburgh 1912 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Slope of main crater at 400 feet | Fritts and Fritts 1982 |