Published October 10, 2019. Updated May 27, 2024. Open access. Peer-reviewed.

Santiago Island Racer (Pseudalsophis hephaestus)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Serpentes | Colubridae | Pseudalsophis hephaestus

English common name: Santiago Island Racer.

Spanish common names: Culebra corredora de Santiago, culebra del dios del fuego.

Recognition: ♂♂ 51.5 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=36.8 cm. ♀♀ 53.6 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=36.8 cm..1 Pseudalsophis hephaestus is one of two snake species occurring on Santiago and Rábida islands, and probably the only one occurring on Sombrero Chino Islet.1,2 It is characterized by having a black dorsum with a series of paired pale goldenrod yellow dorsolateral bands and dark lateral bands (Fig. 1). This pattern differentiates it from the predominantly light gray P. thomasi, a larger snake that does not have goldenrod yellow dorsolateral stripes.1,2 Pseudalsophis hephaestus further differs from P. thomasi by having the supralabial scales conspicuously edged with black pigment.

Figure 1: Individuals of Pseudalsophis hephaestus from Playa Dorada, Santiago Island, Galápagos, Ecuador.

Natural history: Pseudalsophis hephaestus is considered an uncommon species, about 10% as abundant as the co-occurring P. thomasi. Santiago Island Racers are diurnal and terrestrial snakes that inhabit coastal volcanic rock areas, dry grasslands, and seasonally dry forests.1–3 During daytime, they are typically seen swiftly moving on soil or on lava blocks, but they can also climb onto low shrubs during their foraging.1,2 Their activity occurs throughout most of the day, but usually not during hot midday hours.2 Galápagos racer snakes in general are mildly venomous, which means they are dangerous to small prey, but not to humans.1 The diet in P. hephaestus is probably varied, but so far only the lizard Microlophus jacobii has been confirmed as prey item.3 There are recorded instances of predation on members of this species, including by rats4 and hawks.5

Conservation: Near Threatened Not currently at risk of extinction, but requires some level of management to maintain healthy populations..2 Pseudalsophis hephaestus is listed in this category because although the species is not undergoing a decline in the extent and quality of its habitat, it is known from less than 10 localities and is facing the threat of predation by introduced rodents.3 Santiago Island has a long history of introduced species, but the island’s conditions are improving. Pigs were eradicated from Santiago in 1999, followed by goats in 2003, and donkeys in 2005.2

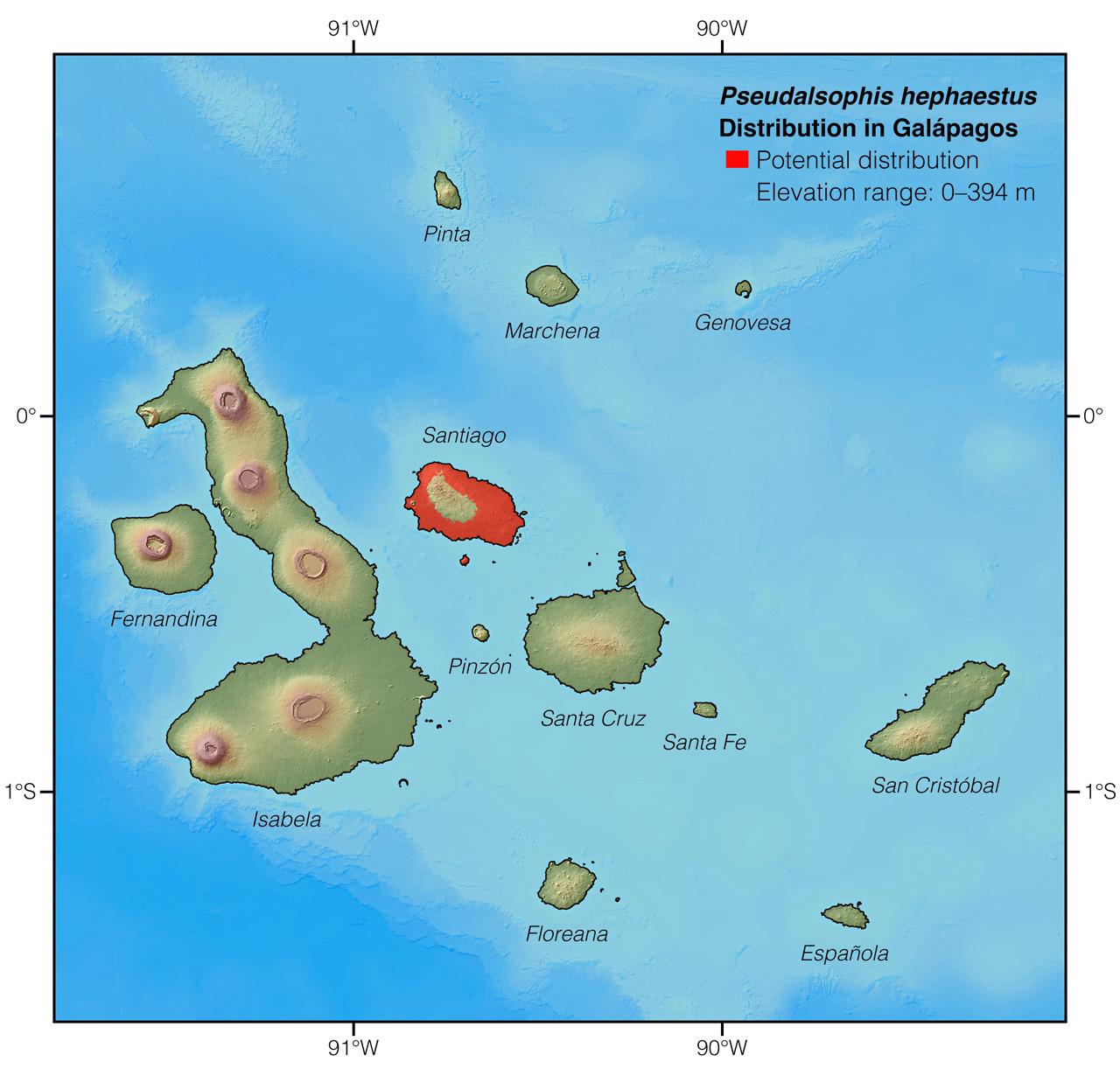

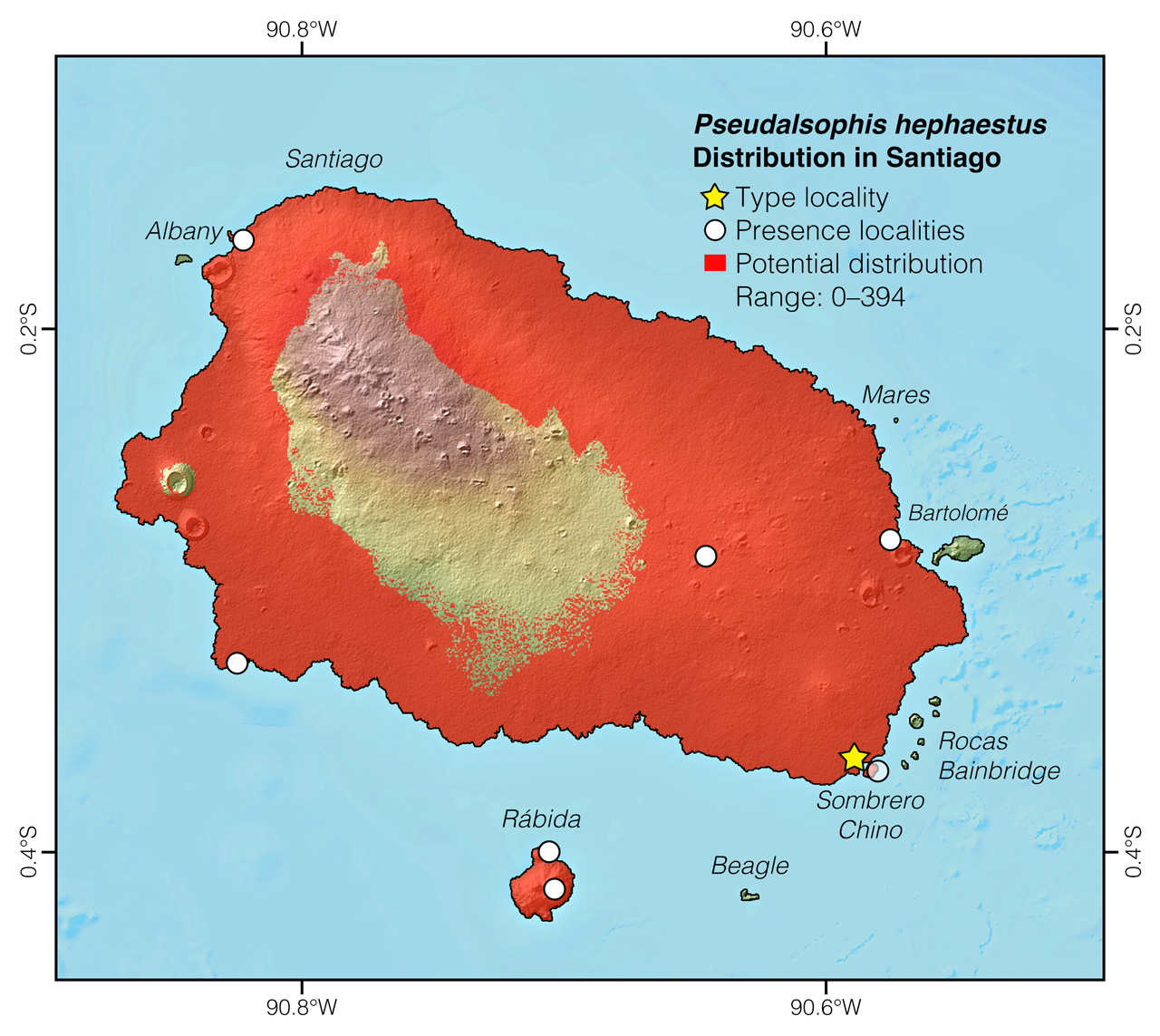

Distribution: Pseudalsophis hephaestus is endemic to an area or approximately 522 km2 in Galápagos, including Santiago Island, Rábida Island, and Sombrero Chino Islet (Figs 2, 3).

Figure 2: Distribution of Pseudalsophis hephaestus in Galápagos. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Figure 3: Distribution of Pseudalsophis hephaestus in Santiago Island. The star corresponds to the type locality: Across Sombrero Chino Islet, Santiago Island. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The generic name Pseudalsophis comes from the Greek words pseudo (=false) and Alsophis (a genus of Caribbean snakes), referring to the similarity between snakes of the two genera.1 The specific epithet hephaestus is the name of the Greek god of fire and volcanoes, and refers to the volcanic environment where this species inhabits.1

See it in the wild: Pseudalsophis hephaestus is the second rarest terrestrial snake in the Galápagos, recorded by tourists at a rate of about once a year. Prime locations for this species include Sombrero Chino Islet and Rábida Island. The best time to look for the racers is during the first hours after sunrise or right before sunset.

Authors: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador. and Juan M GuayasaminbAffiliation: Universidad San Francisco de Quito, Quito, Ecuador.

Academic reviewers: Robert A ThomascAffiliation: Loyola University, New Orleans, United States. and Luis Ortiz-CatedraldAffiliation: Massey University, Palmerston North, New Zealand.

Photographer: Jose VieiraeAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,fAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Arteaga A, Guayasamin JM (2024) Santiago Island Racer (Pseudalsophis hephaestus). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/KNAL2106

Literature cited:

- Zaher H, Yánez-Muñoz MH, Rodrigues MT, Graboski R, Machado FA, Altamirano-Benavides M, Bonatto SL, Grazziotin FG (2018) Origin and hidden diversity within the poorly known Galápagos snake radiation (Serpentes: Dipsadidae). Systematics and Biodiversity 16: 614–642. DOI: 10.1080/14772000.2018.1478910

- Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J, Tapia W, Guayasamin JM (2019) Reptiles of the Galápagos: life on the Enchanted Islands. Tropical Herping, Quito, 208 pp. DOI: 10.47051/AQJU7348

- Cisneros-Heredia DF, Reyes-Puig C (2023) Natural history and conservation of the Galápagos snake radiation. In: Lillywhite HB, Martins M (Eds) Islands and snakes. Oxford University Press, 158–182. DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780197641521.003.0009

- Fritts TH, Fritts PR (1982) Race with extinction: herpetological notes of J. R. Slevin’s journey to the Galápagos 1905–1906. Herpetological Monographs 1: 1–98.

- Jaramillo M, Donaghy-Cannon M, Vargas FH, Parker PG (2016) The diet of the Galapagos hawk (Buteo galapagoensis) before and after goat eradication. Journal of Raptor Research 50: 33–44.

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Pseudalsophis hephaestus in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used. Asterisk (*) indicates type locality.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Crab point | Thomas 1997 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Cumpleaños | Arteaga et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Ensenada Buccaneer | Arteaga et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Highlands of Rábida Island | Cisneros-Heredia & Reyes-Puig 2023 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Highlands of Santiago Island | Cisneros-Heredia & Reyes-Puig 2023 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | In front of Sombrero Chino* | Zaher et al. 2018 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Playa Dorada (in Santiago) | Arteaga et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Rábida | Thomas 1997 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Sombrero Chino | Arteaga et al. 2019 |