Rainforest Hognosed-Pitviper |

Reptiles of Ecuador | Serpentes | Viperidae | Porthidium nasutum

English common names: Rainforest Hognosed-Pitviper, Hog-nosed Viper, .

Spanish common names: Guardacaminos, equis 24, tamagá, víbora pajonera, patoquilla, nariz de hoja.

Recognition: ♂♂ 65.3 cm ♀♀ 63.5 cm. In northwestern Ecuador, the Rainforest Hognosed-Pitviper (Porthidium nasutum) may be recognized by its stout body, triangular-shaped head, heat-sensing pits in the loreal region, upturned snout, and pattern of alternating cream and dark brown rectangular marks on the dorsum. Larger individuals, especially adult females, may lack a discernible pattern, but they always have a sharply upturned snout.

Picture: Adult from Canandé Reserve, Esmeraldas, Ecuador. | |

| |

Picture: Subadult from Canandé Reserve, Esmeraldas, Ecuador. | |

| |

Picture: Juvenile from Canandé Reserve, Esmeraldas, Ecuador. | |

| |

Picture: Juvenile from Canandé Reserve, Esmeraldas, Ecuador. | |

| |

Picture: Juvenile from Canandé Reserve, Esmeraldas, Ecuador. | |

| |

Natural history: Uncommon to locally frequent. Porthidium nasutum is a primarily nocturnal snake that inhabits old-growth to heavily disturbed evergreen lowland forests, marshy areas, plantations (cacao, banana, and cassava), and rural gardens.1–3 Rainforest Hognosed-Pitvipers are mostly active at night, but individuals may also occasionally be seen during the daytime, coiled in the forest floor or crossing paths and roads.4–6 Usually, they hide during the day, sleeping coiled under ground debris, leaf-litter, rocks, logs, or within trunks and roots.6,7 Snakes of this species are mostly terrestrial,3,6,8, but may at times perch on low vegetation or tree trunks 10–150 cm above the ground.3,7 Individuals of P. nasutum are ambush predators. Juveniles feed on earthworms, frogs, toads, and lizards.1,7,9 The young snakes presumably attract prey by means of moving their bright yellow tails as a lure.10 Adults feed on frogs, lizards, snakes (even members of their own species), rodents, and birds.2,6,11 Some prey items are larger than the snakes themselves, accounting for up to 120% of their mass.1 Members of this species are preyed upon by other snakes (such as Clelia clelia)12 and by hawks.13

Porthidium nasutum is a venomous species (LD50 4.6 mg/kg).14 Its venom is hemotoxic, and, in humans, causes intense pain, inflammation, motor impairment, edema, necrosis (death of cells), hemorrhage, and even death.15–17 Critically envenomated victims die from intracranial hemorrhage or from acute renal failure.16–18 However, most bites delivered by members of this species involve only mild to moderate envenomation,19 and in some cases, no envenomation at all (“dry bites”).4 Some compounds of the venom may even have positive therapeutic effects agains leucemia in humans.20 In some parts of the range of P. nasutum, 15–30% of snakebites are attributed to this species.21 Unfortuntaly, the antivenom available in Ecuador does not effectively neutralize the venom of P. nasutum.21 Rainforest Hognosed-Pitvipers rely on their camouflage as a primary defense mechanism,1 but may readily bite if attacked or harassed. Males fight with, and bite, each other over access to females.22 Females “give birth” (the eggs hatch within the mother) to 4–36 (usually 8–18)1,8 young that are 12–20 cm in total length.1 In captivity, individuals can live up to 10 years.1

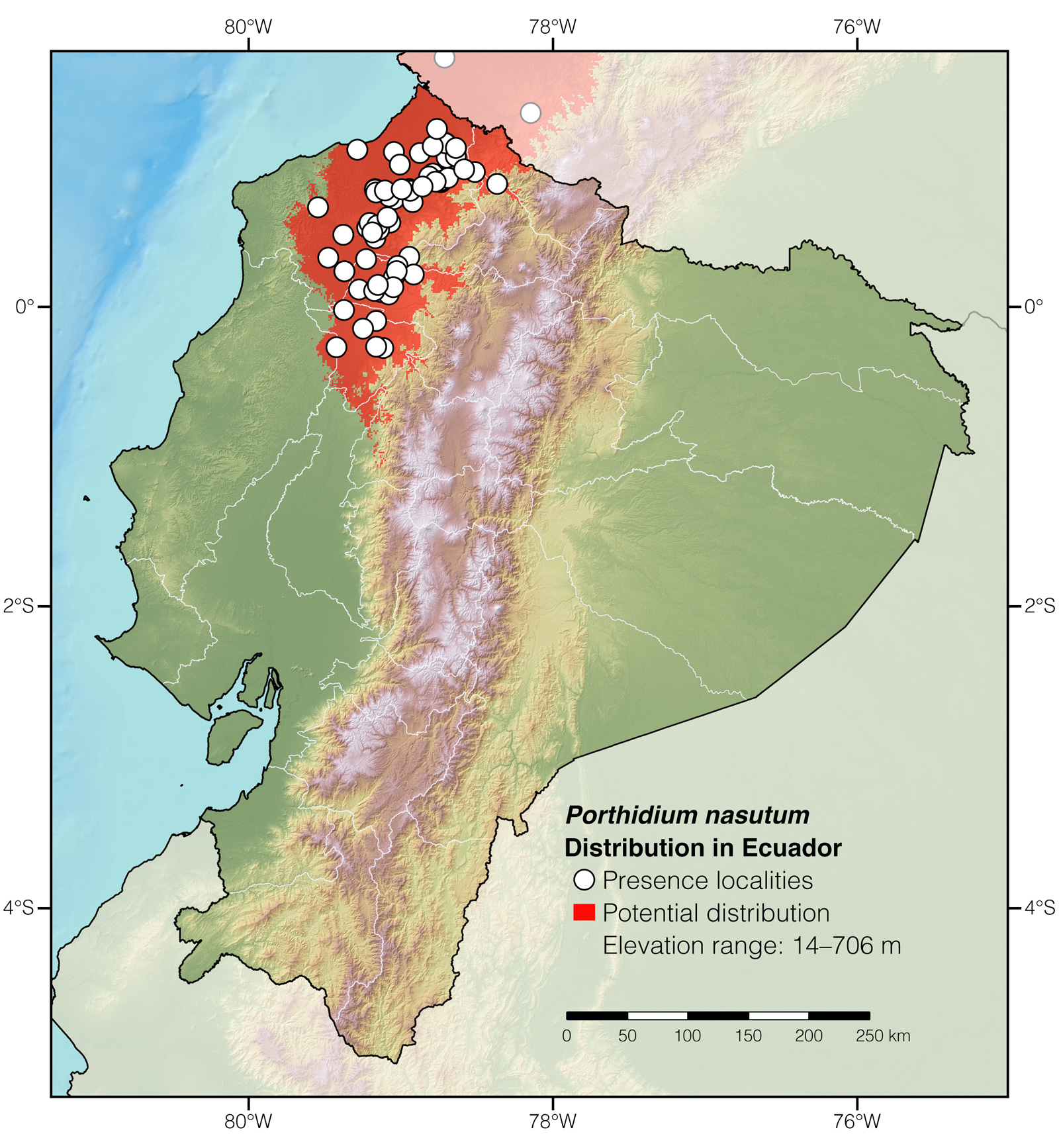

Conservation: Least Concern.23 Porthidium nasutum is listed in this category because the species is widely distributed, frequently encountered in some parts of its range, and is considered to be facing no major immediate extinction threats.23 Despite being listed as Least Concern, P. nasutum faces the threat of habitat loss and direct killing.3

Distribution: Porthidium nasutum is native to the Mesoamerican and Chocoan lowlands from southeastern Mexico to northwestern Ecuador.

Etymology: The generic name Porthidium, which is derived from the Greek word portheo (meaning “destroy”) and the Latin suffix -idus (meaning “having the nature of”), apparently refers to the characteristics of the venom.4 The specific epithet nasutum is a Latin word meaning “large-nosed.”24

See it in the wild: Rainforest Hognosed-Pitvipers can be located with ~2–10% certainty in forested areas throughout the species' area of distribution in Ecuador. Some of the best localities to find Rainforest Hognosed-Pitvipers are Canandé Reserve, Itapoa Rainforest Reserve, and Tesoro Escondido Reserve. The snakes may be located by walking along trails at night.

Special thanks to Gabriela Jaramillo for symbolically adopting the Rainforest Hognosed-Pitviper and helping bring the Reptiles of Ecuador book project to life.

Click here to adopt a species.

Author: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

Photographers: Frank Pichardo,aAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador. Jose Vieira,aAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,bAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador. and Sebastián Di Doménico.

How to cite? Arteaga A (2020) Porthidium nasutum. In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com

Literature cited:

- Valencia JH, Garzón-Tello K, Barragán-Paladines ME (2016) Serpientes venenosas del Ecuador: sistemática, taxonomía, historial natural, conservación, envenenamiento y aspectos antropológicos. Fundación Herpetológica Gustavo Orcés, Quito, 653 pp.

- Álvarez del Toro M (1983) Los reptiles de Chiapas. Instituto de Historia Natural, Tuxtla Gutiérrez, 248 pp.

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- Campbell JA, Lamar WW (2004) The venomous reptiles of the western hemisphere. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, 774 pp.

- McCranie JR (2011) The snakes of Honduras: systematics, distribution, and conservation. Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles, Ithaca, 714 pp.

- Porras L, McCranie JR, Wilson LD (1981) The systematics and distribution of the hognose viper Bothrops nasuta Bocourt (Serpentes: Viperidae). Tulane Studies in Zoology and Botany 22: 85–107.

- Savage JM (2002) The amphibians and reptiles of Costa Rica, a herpetofauna between two continents, between two seas. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 934 pp.

- Heimes P (2016) Snakes of Mexico. Chimaira, Frankfurt, 572 pp.

- Picado C (1931) Serpientes venenosas de Costa Rica. Sección Salud Pública Costa Rica, San José, 219 pp.

- Neill WT (1960) Noteworthy snakes from British Honduras. Herpetologica 16: 146–162.

- Paredes-Montesinos R, García-Padilla E, Mata-Silva V (2015) Porthidium nasutum. Diet. Mesoamerican Herpetology 2: 350–351.

- Delia J (2009) Another crotaline snake prey item of the Neotropical snake Clelia clelia (Daudin 1983). Herpetology Notes 2: 21–22.

- Gerhardt RP, Harris PM, Vásquez MA (1993) Food habits of nesting great black hawks in Tikal National Park, Guatemala. Biotropica 25: 349–352.

- Steinhoff S (2018) LD50 of venomous snakes. Available from: http://snakedatabase.org

- Sittenfeld A, Raventos H, Cruz R, Gutiérrez JM (1991) DNase activity in Costa Rican crotaline snake venoms: quantification of activity and identification of electrophoretic variants. Toxicon 29: 1213–1224.

- Otero R, Gutiérrez J, Mesa MB, Duque E, Rodrı́guez O, Arango JL, Gómez F, Toro A, Cano F, Rodrı́guez LM, Caro E, Martı́nez J, Cornejo W, Gómez LM, Uribe FL, Cárdenas S, Núñez V, Dı́az A (2002) Complications of Bothrops, Porthidium, and Bothriechis snakebites in Colombia. A clinical and epidemiological study of 39 cases attended in a university hospital. Toxicon 40: 1107–1114.

- Schier JG, Wiener SW, Touger M, Nelson LS, Hoffman RS (2003) Efficacy of crotalidae polyvalent antivenin for the treatment of hognosed viper (Porthidium nasutum) envenomation. Annals of Emergency Medicine 41: 391–395.

- Russell FE, Walter FG, Bey TA, Fernandez MC (1997) Snakes and snakebite in Central America. Toxicon 35: 1469–1522.

- Bolaños RA (1983) Serpientes venenosas de Centro América: distribución, características y patrones cardiológicos. Memórias do Instituto Butantan 46: 275–291.

- Bonilla-Porras AR, Jiménez-Ramírez SL, Nuñez-Rangel V, Jiménez Del Rio M, Vélez-Pardo C (2012) Efecto inductor de apoptosis de proteínas obtenidas de veneno de Porthidium nasutum y de extractos etanólicos de Persea americana en líneas celulares de leucemia linfoide aguda (Jurkat Clone E6-1) y mieloide crónica (K-562): estrategias anticancerígenas. Actualidades Biológicas 34: 133–176.

- Otero R, Núñez V, Barona J, Díaz A, Saldarriaga M (2002) Características bioquímicas y capacidad neutralizante de cuatro antivenenos polivalentes frente a los efectos farmacológicos y enzimáticos del veneno de Bothrops asper y Porthidium nasutum de Antioquia y Chocó. Iatreia 15: 5–15.

- Shine R (1994) Sexual size dimorphism in snakes revisited. Copeia 1994: 326–346.

- Lee J, Calderón Mandujano R (2007) Porthidium nasutum. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington D.C., 882 pp.

- Valencia JH, Vaca-Guerrero GV, Garzón K (2011) Natural history, potential distribution and conservation status of the Manabi Hognose Pitviper Porthidium arcosae (Schätti & Kramer, 1993), in Ecuador. Herpetozoa 23: 31–43.