Published August 11, 2021. Updated November 24, 2023. Open access. Peer-reviewed. | Purchase book ❯ |

Forked Sticklizard (Pholidobolus dicrus)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Sauria | Gymnophthalmidae | Pholidobolus dicrus

English common name: Forked Sticklizard.

Spanish common name: Cuilanpalo de franja bifurcada.

Recognition: ♂♂ 16.5 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=5.5 cm. ♀♀ 15.9 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=5.3 cm..1,2 Sticklizards differ from other lizards by having short but well-developed limbs, overlapping striated sub-hexagonal dorsal scales, and a brownish dorsal pattern with longitudinal stripes.3,4 The presence of six-sided finely wrinkled dorsal scales distinguishes Pholidobolus from other co-occurring small brownish lizards such as those in the genera Alopoglossus, Anadia, Andinosaura, Macropholidus, and Riama.5,6 The Forked Sticklizard (P. dicrus) differs from other species of Pholidobolus by having two bright orangish yellow dorsolateral stripes on the first half of the body that merge into a single grayish line.1 Males of P. dicrus differ from females by having more (20–25 versus 7–11) femoral pores and a brighter reddish coloration with ocelli along the flanks.1

Figure 1: Individuals of Pholidobolus dicrus from San Pedro, Tungurahua province, Ecuador. j=juvenile.

Natural history: Pholidobolus dicrus is an uncommonly seen lizard that occurs in the interior, border, and clearings of evergreen montane forests and cloud forests, as well as in tomato and naranjilla plantations.2,7 It is a species of terrestrial habits that spends most of its time foraging on leaf-litter.2 Individuals have only been seen active during sunny days, foraging at ground level, on trees, or on rocky walls covered with tangled vegetation and roots up 3 m above the ground.2 During cloudy days or at night, they remain hidden under rocks, leaf-litter, thick mats of rotten vegetation, moss at the base of trees, or in leaf-litter.2 Pholidobolus dicrus is an oviparous species. Females lay clutches of two eggs under rocks, debris, or in crevices in dirt walls.2 When threatened, Forked Sticklizards take refuge under vegetation or in leaf-litter; if handled, they may shed the tail or bite.2

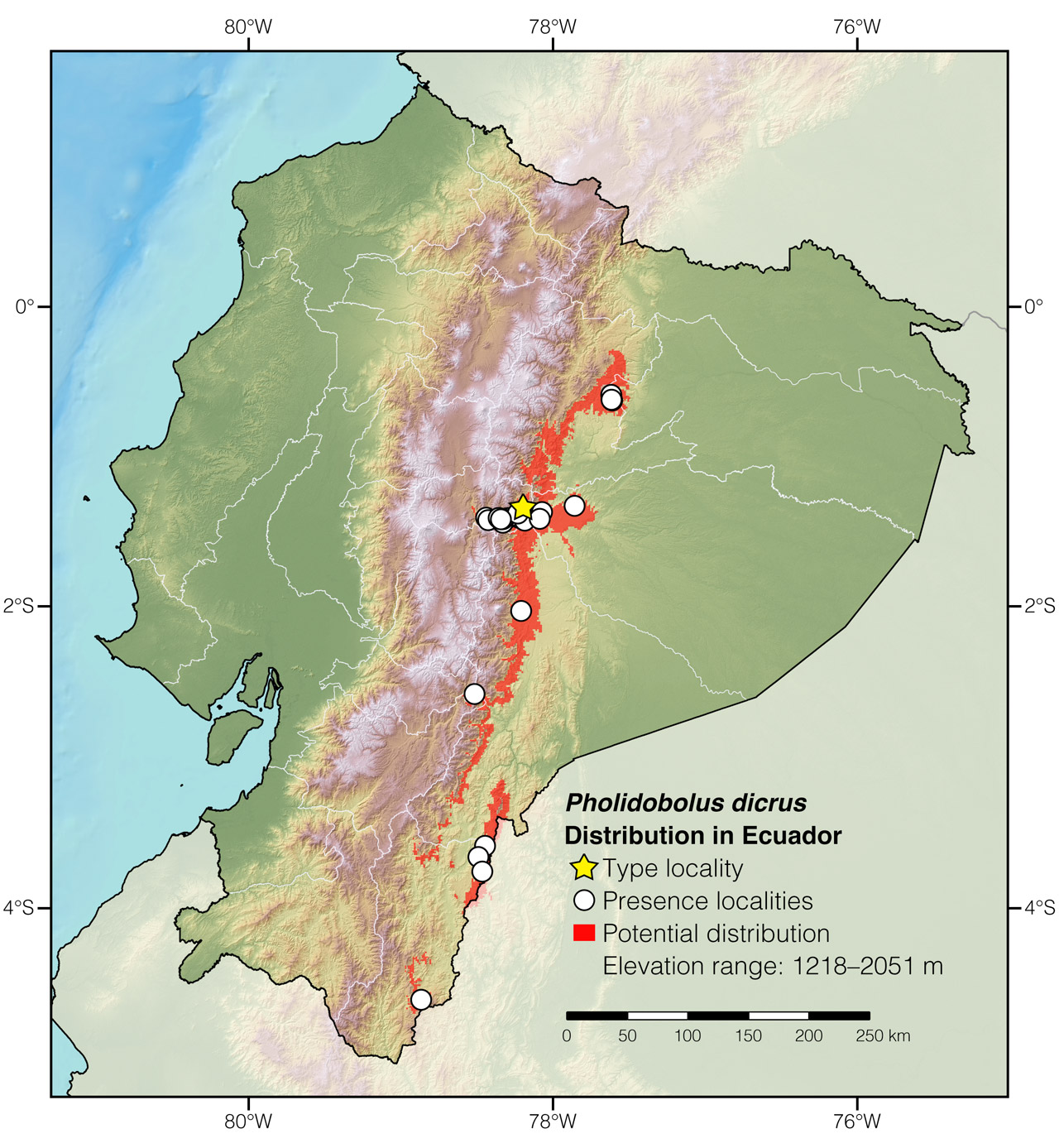

Conservation: Near Threatened Not currently at risk of extinction, but requires some level of management to maintain healthy populations.. Pholidobolus dicrus is proposed to be included in this category, instead of Data Deficient,7 because there is now an adequate number of recent observations (listed in Appendix 1) to make an assessment of the species’ extinction risk. Although P. dicrus has a limited (~7,515 km2; Fig. 2) extent of occurrence, the majority of threats to the long-term survival of the species, such as large-scale mining and agricultural development, are believed to be localized in the southern part of the range. Based on maps of Ecuador’s vegetation cover published in 2012,8 the majority (~82%) of the species’ potential distribution holds continuous areas of pristine forest and ~44% of this area is inside four national parks and five ecological reserves. The most important threat to the long-term survival of P. dicrus is forest destruction due to mining and the expansion of the agricultural frontier. Therefore, the species may qualify for a threatened category in the near future if these threats are not addressed. However, there is no current information on the population trend of the species to determine whether its numbers are declining.

Distribution: Pholidobolus dicrus is endemic to an area of approximately 7,515 km2 along the Amazonian slopes of the Andes in Ecuador (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Distribution of Pholidobolus dicrus in Ecuador. The star corresponds to the type locality: Mapoto, Tungurahua province. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The generic name Pholidobolus comes from the Greek words pholidos (meaning “scale”) and bolos (meaning “lump”),9 and probably refers to the imbricated or mounted scales. The specific epithet dicrus comes from the Greek dikros (=forked) and refers to the dorsal pattern of a forked stripe.1

See it in the wild: Forked Sticklizards can be observed reliably in protected areas such as La Zarza and La Candelaria. They are also particularly common around the town Río Verde, Tungurahua province. Probably the best way to find lizards of this species is to walk along forest borders during sunny mornings as individuals are usually out moving and basking on leaf-litter or on top of vegetation.

Authors: Amanda QuezadaaAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,bAffiliation: Laboratorio de Herpetología, Universidad del Azuay, Cuenca, Ecuador. and Alejandro ArteagacAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

Academic reviewer: Jeffrey D CamperdAffiliation: Department of Biology, Francis Marion University, Florence, USA.

Photographers: Jose VieiraeAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,fAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador. and Alejandro ArteagacAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

How to cite? Quezada A, Arteaga A (2023) Forked Sticklizard (Pholidobolus dicrus). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/VGIP2505

Literature cited:

- Uzzell T (1973) A revision of the genus Prionodactylus with a new genus for P. leucostictus and notes on the genus Euspondylus (Sauria, Teiidae). Postilla 159: 1–67.

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- Montanucci RR (1973) Systematics and evolution of the Andean lizard genus Pholidobolus (Sauria: Teiidae). Miscellaneous Publications of the Museum of Natural History, University of Kansas 59: 1–52.

- Torres-Carvajal O, Venegas P, Lobos SE, Mafla-Endara P, Sales Nunes PM (2014) A new species of Pholidobolus (Squamata: Gymnophthalmidae) from the Andes of southern Ecuador. Amphibian & Reptile Conservation 8: 76–88.

- Peters JA, Donoso-Barros R (1970) Catalogue of the Neotropical Squamata: part II, lizards and amphisbaenians. Bulletin of the United States National Museum, Washington, D.C., 293 pp.

- Doan TM (2003) A new phylogenetic classification for the gymnophthalmid genera Cercosaura, Pantodactylus, and Prionodactylus (Reptilia: Squamata). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 137: 101–115. DOI: 10.1046/j.1096-3642.2003.00043.x

- Cisneros-Heredia DF, Almendáriz A, Yánez-Muñoz M, Brito J (2019) Pholidobolus dicrus. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org. DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-3.RLTS.T44578476A44578482.en

- MAE (2012) Línea base de deforestación del Ecuador continental. Ministerio del Ambiente del Ecuador, Quito, 30 pp.

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington D.C., 882 pp.

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Pholidobolus dicrus in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used. Asterisk (*) indicates type locality.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Guarumales | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2015 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Sardinayacu | Cisneros-Heredia et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Baños and Puyo, between | Uzzell 1973 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Pacto Sumaco, 5.5 km N of | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Napo | Pacto Sumaco, 9.5 km N of | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Napo | Sumaco Camp 1 | This work |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Arajuno, headwaters of | Uzzell 1973 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Tzarentza | This work |

| Ecuador | Tungurahua | Abitagua | Uzzell 1973 |

| Ecuador | Tungurahua | Baños | Uzzell 1973 |

| Ecuador | Tungurahua | El Pailón del Diablo | Photo by Christian Langner |

| Ecuador | Tungurahua | Machay | Albers 2016 |

| Ecuador | Tungurahua | Mera, 7.9 km NE of | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Tungurahua | Puntzan | This work |

| Ecuador | Tungurahua | Reserva La Candelaria | This work |

| Ecuador | Tungurahua | Río Blanco | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2015 |

| Ecuador | Tungurahua | Río Verde, 1 km W of | This work |

| Ecuador | Tungurahua | San Francisco de Mapoto* | Uzzell 1973 |

| Ecuador | Tungurahua | San Pedro | This work |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Alto Machinaza | Almendáriz et al. 2014 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Campamento Las Peñas | Cisneros-Heredia et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Reserva Biológica Cerro Plateado | Photo by Darwin Núñez |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Valle del Río Quimi | Betancourt et al. 2018 |