Published April 20, 2021. Updated May 18, 2024. Open access. | Purchase book ❯ |

Teresita’s Coffee-Snake (Ninia teresitae)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Serpentes | Colubridae | Ninia teresitae

English common names: Teresita’s Coffee-Snake, Chocoan Coffee-Snake.

Spanish common names: Culebra cafetera de Teresita, culebra viejita del Chocó.

Recognition: ♂♂ 49.4 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=38.2 cm. ♀♀ 43.4 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=34.6 cm..1,2 Ninia teresitae can be distinguished from other snakes by having strongly keeled scales arranged in 19 rows at mid-body, two prefrontal scales, dark grayish brown dorsum (Fig. 1), and ventral surfaces of head and body dingy white with various degrees of brown dusting.1,2 This species differs from snakes in the genera Diaphorolepis, Emmochliophis, and Synophis by having paired, instead of fused, prefrontal scales.3,4 Juveniles of N. teresitae have a withish nuchal band that becomes fainter with age.

Figure 1: Individuals of Ninia teresitae: Morromico, Chocó department, Colombia (); Canandé Reserve, Esmeraldas province, Ecuador (). sa=subadult, j=juvenile.

Natural history: Ninia teresitae is a terrestrial, semi-fossorial, nocturnal, and crepuscular snake that inhabits old-growth evergreen forests. The species appears to be more common in human-modified environments such as cattle pastures, plantations,5 rural gardens, and peri-urban areas.1–3 Teresita’s Coffee-Snakes are typically seen foraging on the forest floor at night, but they also have been seen on vegetation 25 cm above the ground.6 During the daytime, individuals hide under bricks, logs, or fallen bromeliads.6 They are harmless and docile snakes; however, during handling, individuals can exhibit anti-predator displays such as hiding the head under body coils, crouching, and cloacal discharges. There are records of Teresita’s Coffee-Snakes being preyed upon by coral snakes (Micrurus transandinus).6 It is expected that, like its congeners, N. teresitae probably feeds on snails, slugs, earthworms, and leeches.3,7

Conservation: Least Concern Believed to be safe from extinction given current circumstances.. Given the recent description of Ninia teresitae,1 this snake has not been formally evaluated by the IUCN Red List. Notwithstanding, the species meets the criteria8 for being included in the Least Concern category. Ninia teresitae is widely distributed throughout the Chocoan lowlands, especially in areas that have not been heavily affected by deforestation, like the Colombian Pacific coast. The species thrives in human-modified habitats and occurs in protected areas. Therefore, it is considered to be facing no major immediate extinction threats.

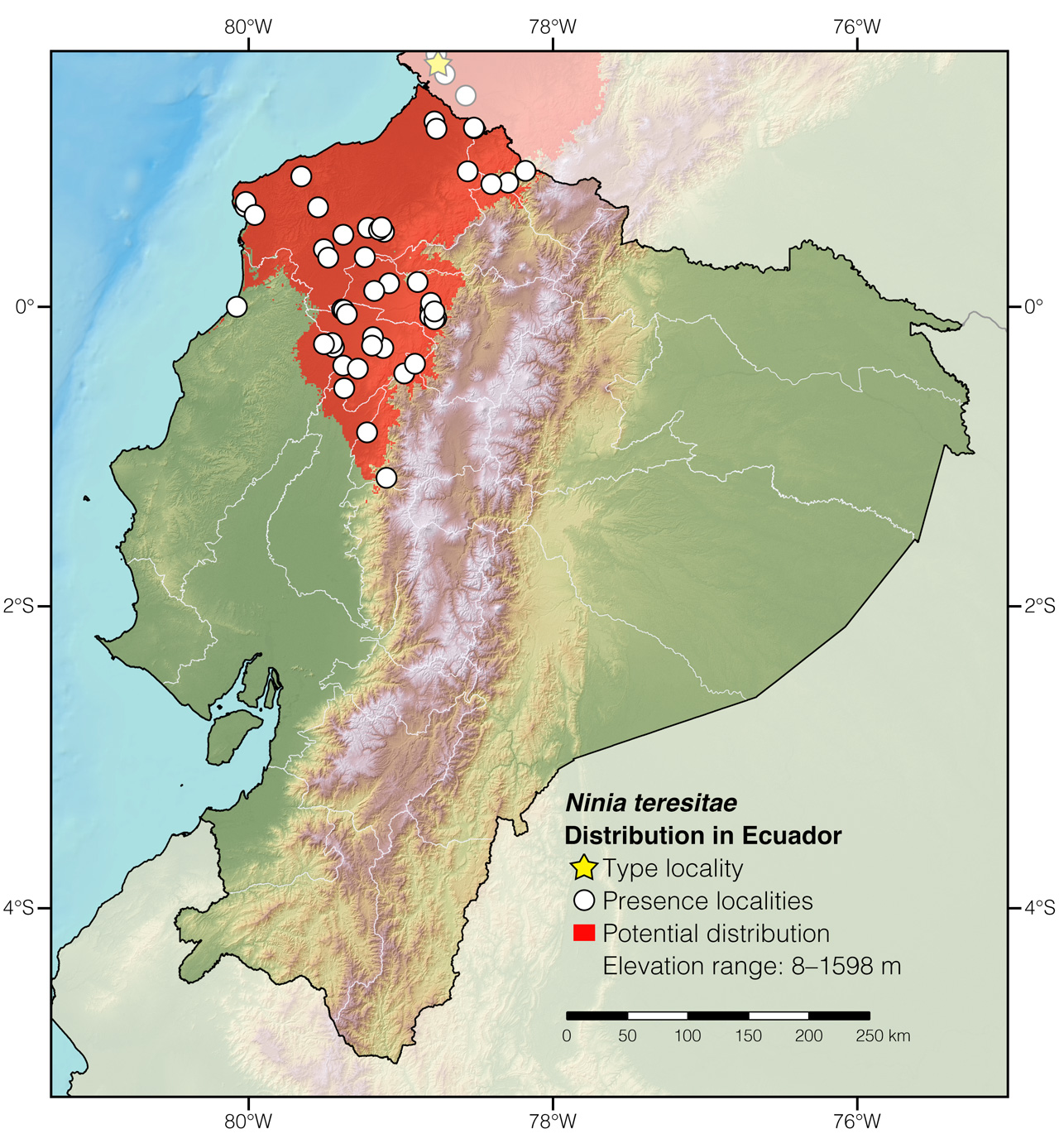

Distribution: Ninia teresitae has a broad distribution range across the Chocó-Magdalena biogeographic region, from northwestern Ecuador (Fig. 2) through the Pacific coast of Colombia, to the basins of the Cauca and Magdalena rivers in northern Colombia.

Figure 2: Distribution of Ninia teresitae in Ecuador. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The generic name Ninia was coined by Baird and Girard in 1853 without any reference regarding its Greek or Latin root. However, Ninia was one of the many names in Greek mythology used to refer to Eurydice, wife of Orpheus, a legendary musician, poet, and prophet. According to the myth, Eurydice dies after her wedding by stepping on a viper. Orpheus goes mad by losing his only love and travels to the underworld to retrieve her. He plays his softened music so extraordinarily that Hades (God of death) and Persephone (Queen of death) allow him to take Eurydice back to the world of the living.9 As far as is known, Ninia does not have Latin roots. The specific epithet teresitae is the Latin translation of the Spanish nickname “Teresita,” given in honor of the grandmother of the first author who described the species.1

See it in the wild: Individuals of Ninia teresitae can be seen active at night in forested or agricultural areas throughout the species’ area of distribution. They are also likely to be found during the daytime by actively removing leaf-litter, piles of leaves, or fallen objects in agricultural areas, especially in African palm plantations. In Ecuador, the area having the greatest number of observations of Teresita’s Coffee-Snake is Mindo, a valley and town in Pichincha province.

Authors: Teddy Angarita-SierraaAffiliation: Yoluka ONG, Fundación de Investigación en Biodiversidad y Conservación, Bogotá, Colombia.,bAffiliation: Vicerrectoría de Investigación, Universidad Manuela Beltrán, Bogotá, Colombia. and Alejandro ArteagacAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.

Photographer: Jose VieiracAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,dAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Angarita-Sierra T, Arteaga A (2021) Teresita’s Coffee-Snake (Ninia teresitae). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/PUID3000

Literature cited:

- Angarita-Sierra T, Lynch JD (2017) A new species of Ninia (Serpentes: Dipsadidae) from Chocó-Magdalena biogeographical province, western Colombia. Zootaxa 4244: 478–492. DOI: 10.11646/zootaxa.4244.4.2

- Angarita-Sierra T (2018) Range expansion in the geographic distribution of Ninia teresitae (Serpentes: Dipsadidae): new localities from northwestern Ecuador. Herpetology Notes 11: 357–360.

- Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Guayasamin JM (2013) The amphibians and reptiles of Mindo. Universidad Tecnológica Indoamérica, Quito, 257 pp.

- Pyron RA, Guayasamin JM, Peñafiel N, Bustamante L, Arteaga A (2015) Systematics of Nothopsini (Serpentes, Dipsadidae), with a new species of Synophis from the Pacific Andean slopes of southwestern Ecuador. ZooKeys 541: 109–147. DOI: 10.3897/zookeys.541.6058

- Lynch JD (2015) The role of plantations of the African palm (Elaeis guineensis Jacq.) in the conservation of snakes in Colombia. Caldasia 37: 169–182.

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- Angarita-Sierra T, Lozano-Daza SA (2019) Life is uncertain, eat dessert first: feeding ecology and prey-predator interactions of the coffee snake Ninia atrata. Journal of Natural History 53: 1401–1420. DOI: 10.1080/00222933.2019.1655105

- IUCN (2001) IUCN Red List categories and criteria: Version 3.1. IUCN Species Survival Commission, Gland and Cambridge, 30 pp.

- Bowra CM (1952) Orpheus and Eurydice. Dancing Times 2: 113–126.

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Ninia teresitae in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used. Asterisk (*) indicates type locality.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Colombia | Nariño | CORPOICA | Pinto-Erazo et al. 2020 |

| Colombia | Nariño | Estación Mar Agrícola | Pinto-Erazo et al. 2020 |

| Colombia | Nariño | Plantación Santa Fe | Angarita-Sierra & Lynch 2017 |

| Colombia | Nariño | Plantación Santa Helena* | Angarita-Sierra & Lynch 2017 |

| Colombia | Nariño | Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Sede Nariño | Pinto-Erazo et al. 2020 |

| Ecuador | Carchi | Chical | Arteaga & Harris 2023 |

| Ecuador | Carchi | Rancho San Marcos | Arteaga & Harris 2023 |

| Ecuador | Carchi | Río San Juan | Arteaga & Harris 2023 |

| Ecuador | Carchi | Tobar Donoso | Arteaga & Harris 2023 |

| Ecuador | Cotopaxi | Bosque Privado El Jardín de los Sueños | Arteaga & Harris 2023 |

| Ecuador | Cotopaxi | Corazón | Angarita-Sierra 2018 |

| Ecuador | Cotopaxi | Las Pampas | Angarita-Sierra 2018 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Alto Tambo | Arteaga & Harris 2023 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Bosque Protector La Perla | Arteaga & Harris 2023 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Calle Mansa | Morales 2004 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Canandé Biological Reserve | Arteaga & Harris 2023 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Centro de Fauna Silvestre James Brown | Arteaga & Harris 2023 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Cerro Ceibo | Arteaga & Harris 2023 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Cresta San Francisco | Arteaga & Harris 2023 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Cupa | Arteaga & Harris 2023 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Finca de Carlos Vásquez | Arteaga & Harris 2023 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Hacienda Equinox | Arteaga & Harris 2023 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Jevon Forest Biological Station | Maynard et al. 2021 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | La Esperanza | Arteaga & Harris 2023 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Las Mareas | Arteaga & Harris 2023 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Quinindé | Angarita-Sierra 2018 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Reserva Itapoa | Arteaga & Harris 2023 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Reserva Tesoro Escondido | Arteaga & Harris 2023 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Tundaloma Lodge | Angarita-Sierra 2018 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Viche | Arteaga et al. 2013 |

| Ecuador | Imbabura | El Tigre | Arteaga & Harris 2023 |

| Ecuador | Imbabura | Lita | Arteaga & Harris 2023 |

| Ecuador | Manabí | El Carmen | Arteaga & Harris 2023 |

| Ecuador | Manabí | El Carmen, 3.6 km N of | Angarita-Sierra 2018 |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Quinta Los Helechos | Angarita-Sierra 2018 |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Río Coaque | Angarita-Sierra & Lynch 2017 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Finca Elenita | Arteaga & Harris 2023 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Hacienda San Vicente | Arteaga & Harris 2023 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | La Celica | Arteaga & Harris 2023 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Mashpi Lodge | Arteaga & Harris 2023 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Mindo | Arteaga & Harris 2023 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Mindo Garden Lodge | Arteaga & Harris 2023 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Mindo–El Cinto | Arteaga & Harris 2023 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Pachijal | Arteaga & Harris 2023 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Pampas Argentinas | Arteaga et al. 2013 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Rancho Suamox | Arteaga & Harris 2023 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Reserva Las Tangaras | Arteaga & Harris 2023 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Séptimo Paraíso Lodge | Arteaga & Harris 2023 |

| Ecuador | Santo Domingo de los Tsáchilas | Finca la Esperanza | Arteaga & Harris 2023 |

| Ecuador | Santo Domingo de los Tsáchilas | Finca Victoria | Arteaga & Harris 2023 |

| Ecuador | Santo Domingo de los Tsáchilas | Puerto Limón | Arteaga & Harris 2023 |

| Ecuador | Santo Domingo de los Tsáchilas | Río Baba | Arteaga & Harris 2023 |

| Ecuador | Santo Domingo de los Tsáchilas | Río Toachi | Arteaga & Harris 2023 |

| Ecuador | Santo Domingo de los Tsáchilas | Santo Domingo | Arteaga & Harris 2023 |