Published March 14, 2022. Updated January 25, 2024. Open access. | Purchase book ❯ |

Peruvian Lava-Lizard (Microlophus peruvianus)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Sauria | Tropiduridae | Microlophus peruvianus

English common names: Peruvian Lava-Lizard, Perú Pacific Iguana.

Spanish common names: Lagartija de lava Peruana, capón de Perú, lagartija de las playas, lagartija de la costa, chucos, qalaywa.

Recognition: ♂♂ 30 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=11.6 cm. ♀♀ 22.1 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=9.7 cm..1,2 In continental Ecuador, lava lizards differ from other lizards by having keeled scales on the tail, a skin fold above the shoulder, and a conspicuously enlarged interparietal scale.1–4 These characteristics differentiates them from lizards in the genera Anolis, Holcosus, Polychrus, and Stenocercus. The Peruvian Lava-Lizard (Microlophus peruvianus) can be easily differentiated from the only other lava lizard in continental Ecuador (M. occipitalis) by having smooth granular dorsal scales, lateral folds, and a black band on the throat (instead of keeled imbricate dorsal scales, no lateral folds, and no black throat patch in M. occipitalis).1,5 Juveniles have a bright yellow spot on the groin, which disappears in adult males and remains in adult females.6 Males have well-defined black bands in the form of chevrons across the base of the throat; while in females the bands are pale.1

Figure 1: Individuals of Microlophus peruvianus from Playa Ballenita, Santa Elena province, Ecuador.

Natural history: Microlophus peruvianus is less abundant (3.75–6.4 vs 8 individuals/hectare)7,8 than the co-occurring M. occipitalis. It inhabits coastal areas with xeric vegetation,1,9,10 either in pristine habitats or near human-modified environments.11,12 This species is usually found within 100 m of seawater,13 but it also occurs in other habitats inland, in the desert and river valleys.14 It occupies sandy beaches, salt crust beaches, sand dunes, the marine intertidal zone, rocky areas, mud cliffs, rocky riversides, rock walls, and houses.11–15 Peruvian Lava-Lizards are diurnal, apparently with unimodal activity16 during the sunniest hours of the day. During the summer they come out of their burrows earlier. When the sky is overcast, they reduce their activity and their body temperature, which remains between 33 and 36°C.9,10 Individuals actively forage and bask on sand, rocks, logs, and bushes.10–12 When not active, Peruvian Lava-Lizards hide inside crevices, under rocks, logs, or in caves dug by themselves or abandoned by other animals.2,12 Microlophus peruvianus has a generalist and opportunistic diet. These lizards consume a wide variety of arthropods,1,2,16,17 and have been used by humans for the control of ectoparasites in seabirds16 and mice.15 They feed on fauna associated with the coastal zone and intertidal zone, including animal remains such as pieces of mollusks. They take advantage of the decomposition of animals to hunt scavenging arthropods.18 Peruvian Lava-Lizards also practice saurophagy, preying upon geckos of the genus Phyllodactylus,19 or even members of their own species, where adults cannibalize live20 or dead21 juveniles. Their diet is complemented with algae and plant remains such as flowers, leaves, and fruits.9,21 Members of this species are preyed upon by birds of prey such as the Barn Owl (Tyto alba) and the American Kestrel (Falco sparverius),22,23 and parasitized by nematodes.24–26 Males are territorial and aggressive towards intruders.2 In the presence of a disturbance, these fast and agile lizards usually try to flee or take refuge in crevices, among large rocks, under logs, construction materials, vegetation, or in the sand.8,9,17 On occasion, they may adopt bipedal posture when running.2 If captured, they may readily shed the tail.6 Microlophus peruvianus is an oviparous species2 with a reproductive period that goes from July to December. Females lay up to 6 eggs per clutch.1,15

Conservation: Least Concern Believed to be safe from extinction given current circumstances..14 Microlophus peruvianus is listed in this category because the species has a wide distribution along the Pacific coast of South America and current knowledge indicates that there are no widespread threats affecting its long-term survival.14 In Peru, this species is found in the Paracas National Reserve and San Fernando National Reserve; however, it has not been recorded in any protected area in Ecuador.14 It is presumed that M. peruvianus has been introduced to several islands within its distribution.13,14

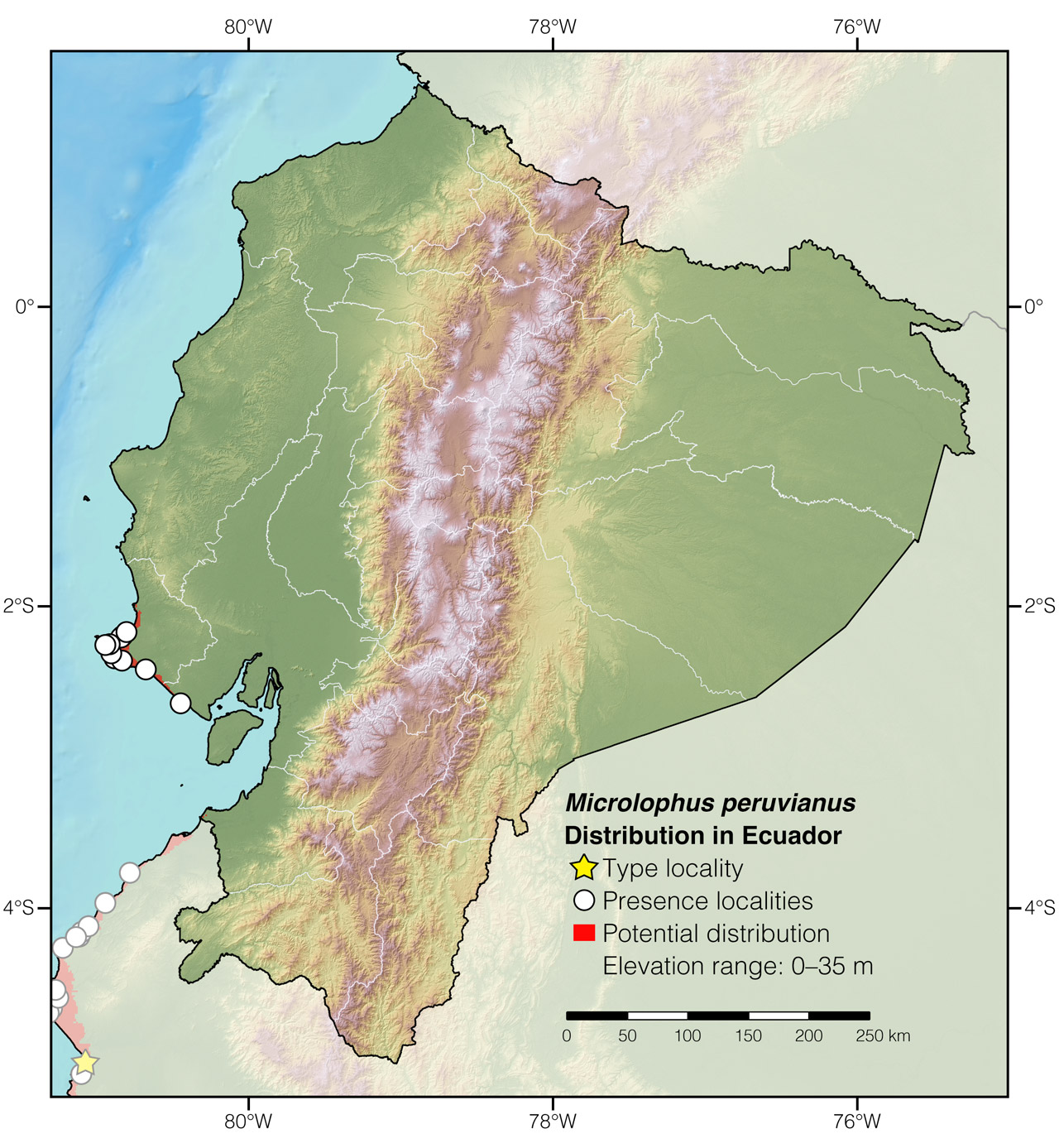

Distribution: Microlophus peruvianus is widely distributed over a ~2000 km stretch of coastline along the Pacific from southwestern Ecuador to southwestern Perú (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Distribution of Microlophus peruvianus in Ecuador. The star corresponds to the type locality: Paita, Piura department, Peru. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The generic name Microlophus comes from the Greek words mikros (=small) and lophos (=crest),27 and refers to the reduced dorsal crest in this species.28 The specific epithet peruvianus refers to Peru, the country of origin of the holotype of this species.29

See it in the wild: Peruvian Lava-Lizards can be observed with almost complete certainty along the coast and beaches of the Santa Elena peninsula in western Ecuador. The localities having the greatest number of observations are La Chocolatera and Playa de Ballenita. The lizards can be easily observed during sunny hours, basking or moving, especially on large rocks on the sand.

Author: Amanda QuezadaaAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,bAffiliation: Laboratorio de Herpetología, Universidad del Azuay, Cuenca, Ecuador.

Editor: Alejandro ArteagacAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

Photographer: Alejandro ArteagacAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

How to cite? Quezada A (2024) Peruvian Lava-Lizard (Microlophus peruvianus). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/GFGV8184

Literature cited:

- Dixon JR, Wright JW (1975) A review of the lizards of the iguanid genus Tropidurus in Perú. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County Contributions in Science 271: 1–39.

- Péfaur JE, Núñez A, López E, Dávila J (1978) Distribución y clasificación de los reptiles del departamento de Arequipa. Bulletin de l’Institut Français d’Études Andines 7: 129–139.

- Duméril AMC, Bibron G (1837) Erpétologie générale ou Histoire Naturelle complète des Reptiles. Librairie Encyclopédique de Roret, Paris, 571 pp. DOI: 10.5962/bhl.title.45973

- Peters JA, Donoso-Barros R (1970) Catalogue of the Neotropical Squamata: part II, lizards and amphisbaenians. Bulletin of the United States National Museum, Washington, D.C., 293 pp.

- Boulenger GA (1885) Catalogue of the lizards in the British Museum. Taylor & Francis, London, 497 pp.

- Novoa JC, Hooker Mantilla Y, García Olaechea A (2010) Isla Foca: Guía de fauna silvestre. CONCYTEC – NCI, Lima, 112 pp.

- Gálvez M, Barrionuevo R, Charcape M (2006) El Desierto de Sechura: Flora, fauna y relaciones ccológicas. Universalia 11: 33–43.

- Tello-Albarado BM (2017) Estructura poblacional de Microlophus peruvianus en el supralitoral del distrito de Huanchaco. BSc thesis, Universidad Nacional de Trujillo, 48 pp.

- Catenazzi A, Carrillo J, Donnelly MA (2005) Seasonal and geographic eurythermy in a coastal Peruvian lizard. Copeia 2005: 713–723. DOI: 10.1643/0045-8511(2005)005[0713:SAGEIA]2.0.CO;2

- Huey RB (1974) Winter thermal ecology of the iguanid lizard Tropidurus peruvianus. Copeia 1974: 149. DOI: 10.2307/1443017

- Paniura-Palma GA (2016) Preferencia de campos vitales, zonas de actividad y refugio de la herpetofauna presente en la localidad de Nuevo Perú, Valle de Majes, Arequipa. BSc thesis, Universidad Nacional de San Agustín de Arequipa, 205 pp.

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- Pérez J, Lleellish M (2015) Terrestrial reptiles from San Lorenzo Island, Lima, Peru. Revista Peruana de Biología 22: 119–122. DOI: 10.15381/rpb.v22i1.11130

- Venegas P, Yánez-Muñoz M, Sánchez J (2017) Microlophus peruvianus. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org. DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-2.RLTS.T178311A68973390.en

- Péfaur JE, López-Tejeda E (1983) Ecological notes on the lizard Tropidurus peruvianus in southern Peru. Journal of Arid Environments 6: 155–160. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-1963(18)31528-3

- Pérez J, Balta K (2007) Ecología de la comunidad de saurios diurnos de la Reserva Nacional de Paracas, Ica, Perú. Revista Peruana de Biología 13: 169–176.

- Quispitúpac E, Pérez J (2008) Dieta de la lagartija de las playas Microlophus peruvianus (Reptilia: Tropiduridae) en la playa Santo Domingo, Ica, Perú. Revista Peruana de Biología 15: 129–130. DOI: 10.15381/rpb.v15i2.1739

- Murrugarra-Bringas VY (2016) Sucesión de artropofauna en cadáveres de cerdos (Sus scrofa L., 1758), en Pantanos de Villa, Chorrillos, Lima, Perú. MSc thesis, Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, 123 pp.

- Catenazzi A (2006) Microlophus peruvianus: saurophagy. Herpetological Review 37: 90.

- Pérez J (2005) Microlophus peruvianus: cannibalism. Herpetological Review 36: 63.

- Donoso-Barros R (1948) Alimentación de Tropidurus peruviensis (Lesson). Boletín del Museo Nacional de Historia Natural (Chile) 24: 213–216.

- Ramírez O, Béarez P, Arana M (2000) Observaciones sobre la dieta de la Lechuza de los Campanarios en la quebrada de Los Burros (Dpto. Tacna, Perú). Bulletin de l’Institut Français d’Études Andines 29: 233–240.

- Online multimedia.

- Pérez J, Balta K, Salizar P, Sánchez L (2007) Nematofauna de tres especies de lagartijas (Sauria: Tropiduridae y Gekkonidae) de La Reserva Nacional de Paracas, Ica, Perú. Revista Peruana de Biología 14: 43–45. DOI: 10.15381/rpb.v14i1.1755

- Goldberg SR, Burse CR (2009) Helminths from seven species of Microlophus (Squamata: Tropiduridae) from Peru. Salamandra 45: 125–128.

- Calisaya JL, Cordova E (1997) Tres nuevas especies de Parapharyngodon (Nematoda, Oxiuroidea) parásitas de Tropidurus peruvianus del sur del Perú. Rebiol 17: 45–54.

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington D.C., 882 pp.

- Frost DR (1992) Phylogenetic analysis and taxonomy of the Tropidurus group of lizards (Iguania: Tropidurudae). American Museum Novitates 3033: 1–68.

- Lesson RP (1830) Description de quelques reptiles nouveaux ou peu connus. In: Duperrey MLI (Ed) Voyage autour du monde: exécuté par ordre du roi, sur la corvette de Sa Majesté, la Coquille, pendant les années 1822, 1823, 1824, et 1825. Arthur Bertrand, Paris, 1–65.

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Microlophus peruvianus in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used. Asterisk (*) indicates type locality.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Playa el Pelado | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Santa Elena | Anconcito | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Santa Elena | Atahualpa | Mármol-Guijarro & Galarza-Verkovitch 2020 |

| Ecuador | Santa Elena | Ballenita | This work; Fig. 1 |

| Ecuador | Santa Elena | Capaes | Amanda Quezada, pers. obs. |

| Ecuador | Santa Elena | Chanduy | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Santa Elena | Punta Blanca | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Santa Elena | Punta Carnero | USNM 201387; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Santa Elena | Salinas | USNM 201374; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Santa Elena | Salinas, 3 km SE of | USNM 201379; VertNet |

| Perú | Piura | Cabo Blanco | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Perú | Piura | Los Órganos | MCZ R-160800; VertNet |

| Perú | Piura | Los Organos, 3.7 km NE of | Dixon and Wright 1975 |

| Perú | Piura | Negritos | CAS 8785; VertNet |

| Perú | Piura | Paita* | Dixon and Wright 1975 |

| Perú | Piura | Punta Aguja | Catenazzi 2006 |

| Perú | Piura | Punta Balcones | Online multimedia |

| Perú | Piura | Punta Ballenas | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Perú | Piura | Punta Veleros | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Perú | Piura | Talara | Van Leeuwen et al. 2011 |

| Perú | Piura | Talara, 4 km N of | Dixon and Wright 1975 |

| Perú | Tumbes | Cancas, 1.2 km S of | Dixon and Wright 1975 |

| Perú | Tumbes | Cardalito | SDNHM 30844; VertNet |