Published March 19, 2021. Updated January 8, 2024. Open access. | Purchase book ❯ |

Spiny Dwarf-Gecko (Lepidoblepharis conolepis)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Sauria | Sphaerodactylidae | Lepidoblepharis conolepis

English common names: Spiny Dwarf-Gecko, Spiky Dwarf-Gecko, Tandapi Scaly-eyed Gecko.

Spanish common names: Hojarito pinchudo, salamanquesa de Tandapi.

Recognition: ♂♂ 8.7 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=4.2 cm. ♀♀ 9.0 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=4.4 cm..1 Dwarf geckos differ from other lizards based on their small size, lack of movable eyelids, presence of a scaly supraciliary flap, and their leaf-litter-dwelling habits.2,3 The Spiny Dwarf-Gecko (Lepidoblepharis conolepis) is the only member of its genus occurring in the cloud forests of northwestern Ecuador.4 It has a brownish dorsum with (usually) a light-cream arc connecting both eyes on top of the head.4 This species is one of two Ecuadorian Lepidoblepharis having sub-equal (mostly homogeneous) conical dorsal scales.1,5 The other is L. grandis, a species that occurs below the known elevation range of L. conolepis, in the Chocó rainforest. Males of L. conolepis differ from females by being more brightly colored and by having a silver escutcheon, a characteristic concentration of holocrine secretory glands, on the belly.1

Figure 1: Individuals of Lepidoblepharis conolepis from Ecuador: Otonga Reserve, Cotopaxi province (), Santa Lucía Cloud Forest Reserve, Pichincha province (). sa=subadult, j=juvenile.

Natural history: Lepidoblepharis conolepis is a rarely seen6 cryptozoic (preferring moist, shaded microhabitats), terrestrial, and diurnal gecko that inhabits old-growth cloud forests.4 Spiny Dwarf-Geckos spend most of their lives in thick accumulations of leaf-litter,4–7 especially along streams. However, they have been found in walls and roofs of field stations in the forest.4 When not active, geckos of this species hide under logs, rocks, or piles of leaf-litter,6,8 but some individuals have been seen sleeping on leaves up to 60 cm above the ground.4 Spiny Dwarf-Geckos are insectivorous, but the specific insects consumed are not known.8 There are records of snakes (Erythrolamprus albiventris) preying upon geckos of this species.4 In the presence of a disturbance, individuals of L. conolepis will quickly flee under leaf-litter. If captured, they can readily shed the tail as well as portions of their skin.4 Spiny Dwarf-Geckos are susceptible to high temperatures, dying if exposed to the sun or even if handled for longer than just a few seconds.4 Females lay eggs under leaf-litter, soft-soil, and in crevices in dirt walls.8

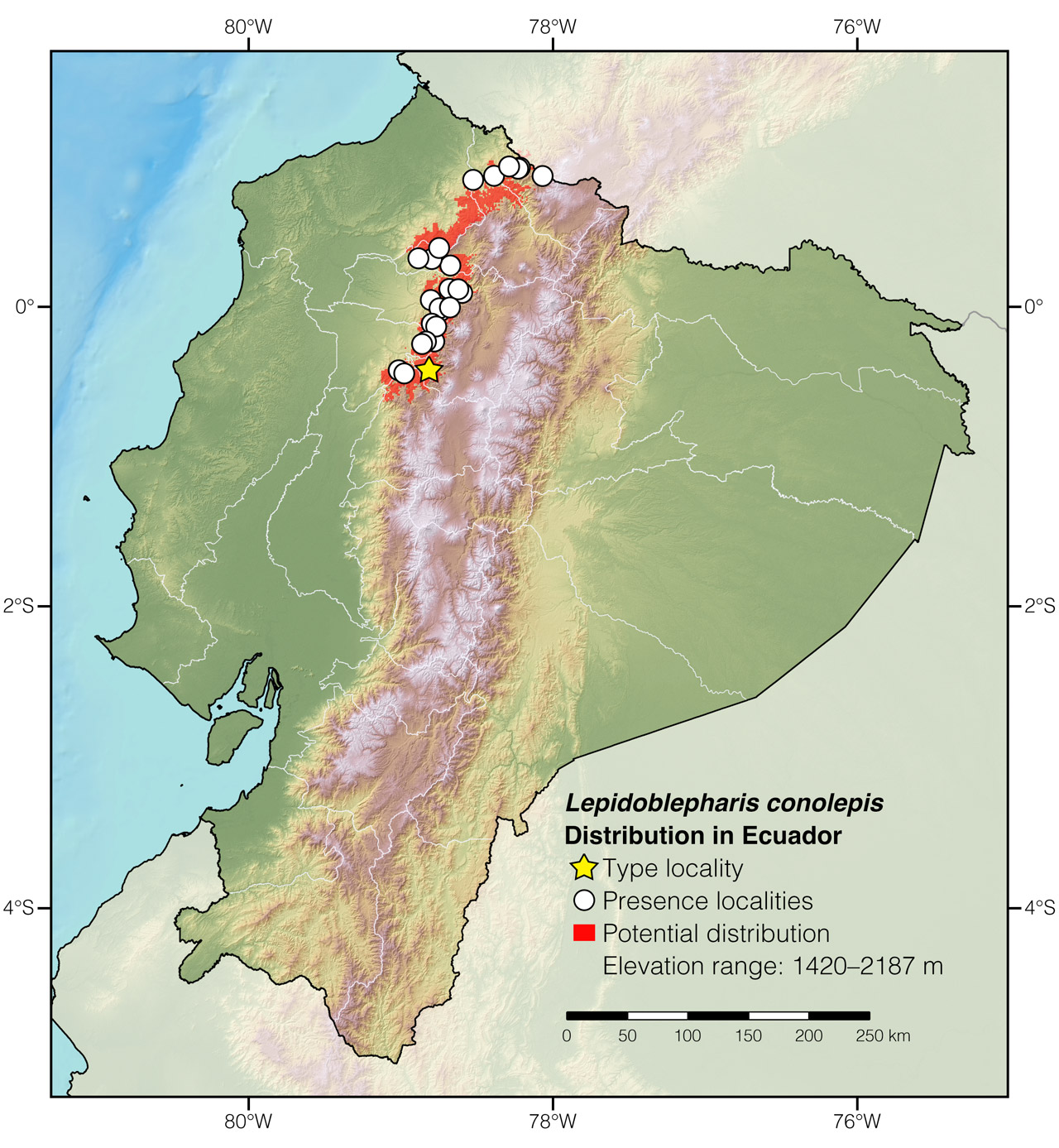

Conservation: Near Threatened Not currently at risk of extinction, but requires some level of management to maintain healthy populations.. Lepidoblepharis conolepis is proposed to be assigned in this category, instead of Endangered,9 because there is novel information that suggests that the species is more widely distributed (4,695 km2; Fig. 2) than previously thought (170 km2).9 Lepidoblepharis conolepis does not meet the IUCN criteria10 for qualifying as Vulnerable11 or Endangered9 because the species has been recorded at 25 localities (including 7 privately protected areas; see Appendix 1) and it is distributed over an area that retains most (~73.7%) of its forest cover.12 However, some populations of L. conolepis are likely to be declining due to deforestation by logging13 and large-scale mining,14 especially in the provinces Carchi and Imbabura, where only eight populations (Appendix 1) are known. Therefore, the species may qualify for a threatened category in the near future if these threats are not addressed.

Distribution: Lepidoblepharis conolepis is endemic to an area of approximately 4,695 km2 in the Pacific slopes of the Andes in northwestern Ecuador (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Distribution of Lepidoblepharis conolepis in Ecuador. The star corresponds to the type locality: Tandapi, Pichincha province. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The generic name Lepidoblepharis comes from the Greek words lepidos (=scale) and blepharis (=eyelash),15 and refers to the scaly supraciliary flaps.16 The specific epithet conolepis is derived from the Greek words konikos (=cone-like) and lepis (=scale).15 It refers to the conical dorsal scales.1

See it in the wild: Spiny Dwarf-Geckos are recorded rarely, no more than once every few months, probably due to their small size and secretive habits. At Santa Lucía Cloud Forest Reserve and at Otonga Reserve, however, lizards of this species may be recorded at a rate of about 1–4 individuals per day when sampling leaf-litter.

Acknowledgments: Special thanks to Amanda Quezada, Frank Pichardo, and Harry Turner for helping locate some of the specimens of Lepidoblepharis conolepis photographed in this account. This account was published with the support of Secretaría Nacional de Educación Superior Ciencia y Tecnología (programa INEDITA; project: Respuestas a la crisis de biodiversidad: la descripción de especies como herramienta de conservación; No 00110378), Programa de las Naciones Unidas (PNUD), and Universidad San Francisco de Quito (USFQ).

Author: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

Photographer: Jose VieiraaAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,bAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Arteaga A (2024) Spiny Dwarf-Gecko (Lepidoblepharis conolepis). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/YYHK4884

Literature cited:

- Avila-Pires TCS (2001) A new species of Lepidoblepharis (Reptilia: Squamata: Gekkonidae) from Ecuador, with a redescription of L. grandis Miyata, 1985. Occasional Paper of the Sam Noble Oklahoma Museum of Natural History 11: 1–11.

- Peters JA, Donoso-Barros R (1970) Catalogue of the Neotropical Squamata: part II, lizards and amphisbaenians. Bulletin of the United States National Museum, Washington, D.C., 293 pp.

- Batista A, Ponce M, Vesely M, Mebert K, Hertz A, Köhler G, Carrizo A, Lotzkat S (2015) Revision of the genus Lepidoblepharis (Reptilia: Squamata: Sphaerodactylidae) in Central America, with the description of three new species. Zootaxa 3994: 187–221. DOI: 10.11646/zootaxa.3994.2.2

- Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Guayasamin JM (2013) The amphibians and reptiles of Mindo. Universidad Tecnológica Indoamérica, Quito, 257 pp.

- Miyata K (1985) A new Lepidoblepharis from the Pacific slope of the Ecuadorian Andes (Sauria: Gekkonidae). Herpetologica 41: 121–127.

- Carrillo Ponce EO (2015) Caracterización de la herpetofauna presente en la Reserva Ecológica Bosque Nublado “Santa Lucía.” BSc thesis, Quito, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador, 133 pp.

- Ríos Alvear G, Reyes-Puig C (2016) Reptilia, Sauria, Sphaerodactylidae, Lepidoblepharis conolepis Avila-Pires, 2001: distribution extension in northern Ecuador. Check List 12: 1–3. DOI: 10.15560/12.5.1983

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- Cisneros-Heredia DF, Yánez-Muñoz M (2017) Lepidoblepharis conolepis. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org. DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-2.RLTS.T44579339A44579343.en

- IUCN (2001) IUCN Red List categories and criteria: Version 3.1. IUCN Species Survival Commission, Gland and Cambridge, 30 pp.

- Reyes-Puig C (2015) Un método integrativo para evaluar el estado de conservación de las especies y su aplicación a los reptiles del Ecuador. MSc thesis, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador, 73 pp.

- MAE (2012) Línea base de deforestación del Ecuador continental. Ministerio del Ambiente del Ecuador, Quito, 30 pp.

- Tolhurst BA, Aguirre Peñafiel V, Mafla-Endara P, Berg MJ, Peck MR, Maddock ST (2016) Lizard diversity in response to human-induced disturbance in Andean Ecuador. Herpetological Journal 26: 33–39.

- Guayasamin JM, Cisneros-Heredia DF, Vieira J, Kohn S, Gavilanes G, Lynch RL, Hamilton PS, Maynard RJ (2019) A new glassfrog (Centrolenidae) from the Chocó-Andean Río Manduriacu Reserve, Ecuador, endangered by mining. PeerJ 7: e6400. DOI: 10.7717/peerj.6400

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington D.C., 882 pp.

- Peracca MG (1897) Viaggio del Dr. Enrico Festa nell'Ecuador e regioni vicine. Bolletino dei Musei di Zoologia ed Anatomia Comparata della Università di Torino 12: 1–20. DOI: 10.5962/bhl.part.4563

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Lepidoblepharis conolepis in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used. Asterisk (*) indicates type locality.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Ecuador | Carchi | Chical, 1.7 km SW of | Arteaga et al. 2013 |

| Ecuador | Carchi | Chilma Bajo | Arteaga et al. 2013 |

| Ecuador | Carchi | Dracula Reserve | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Carchi | El Cielito | Ríos Alvear & Reyes Puig 2016 |

| Ecuador | Carchi | Río Tigre | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Cotopaxi | Bosque Integral Otonga | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Cotopaxi | Las Pampas | Arteaga et al. 2013 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | El Cristal | Crump & Lynch 1995 |

| Ecuador | Imbabura | Junín | Arteaga et al. 2013 |

| Ecuador | Imbabura | Los Cedros Reserve | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Imbabura | Río Manduriacu Reserve | Lynch et al. 2014 |

| Ecuador | Imbabura | Toisán | Andy Proaño, pers. comm. |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | 11.5 km N Mindo | Miyata 1985 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Birdwatcher’s House | Photo by Vinicio Pérez |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Chiriboga | EPN 7064; examined |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Curipogio | Ríos Alvear & Reyes Puig 2016 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | El Golán | Ríos Alvear & Reyes Puig 2016 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Las Gralarias Reserve | Krynak pers. comm. |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Mindo, 4 mi S of | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Santa Lucía Cloud Forest Reserve | MZUTI 4160; examined |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Saragoza–Río Cinto | Ríos Alvear & Reyes Puig 2016 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Tandapi* | Avila-Pires 2001 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Tandayapa, 2 km SE of | Miyata 1985 |

| Ecuador | Santo Domingo de los Tsáchilas | Estación Científica Río Guajalito | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Santo Domingo de los Tsáchilas | Las Palmeras | Ríos Alvear & Reyes Puig 2016 |