Yellow-bellied Sea-Snake |

Reptiles of Ecuador | Serpentes | Elapidae | Hydrophis | Hydrophis platurus

English common names: Yellow-bellied Sea-Snake, Yellowbelly Sea-Snake, Pelagic Sea-Snake.

Spanish common names: Serpiente marina de vientre amarillo, serpiente marina barriga amarilla, serpiente marina pelágica, serpiente de mar.

Recognition: ♂♂ 72 cm ♀♀ 114.3 cm. In Ecuador, the Yellow-bellied Sea-Snake (Hydrophis platurus) is the only snake having a paddle-shaped tail adapted to swimming and a sharply demarcated bicolored longitudinal yellow and dark-blue to black pattern.

Picture: Adult. Tonsupa. Esmeraldas, Ecuador. | |

| |

Picture: Adult. Parque Nacional Natural Utría. Chocó, Colombia. | |

| |

Natural history: Extremely rare throughout much of its range, including Ecuador, but extremely common in certain feeding and breeding areas. Hydrophis platurus is mostly diurnal,1 but also nocturnal,2,3 and is the world's most pelagic snake, living its entire life cycle at sea.4 Yellow-bellied Sea-Snakes are usually found drifting 1–20 km offshore4 in areas having mean monthly water temperatures of 28–32°C.5 Here, thousands of snakes (up to 12 snakes per m2)6 may congregate where lines of debris 3–6 m wide4 and several kilometers long are maintained by convergence of oceanic currents.7,8

Occasionally, individuals of Hydrophis platurus enter mangrove swamps9 and even tidal waters of rivers up to 5 km from the river mouth.10 Some individuals are washed ashore during rough weather.11,12 Once on the beach, Yellow-bellied Sea-Snakes are comparatively helpless, and soon die from heat or exhaustion.11 Despite being entirely marine, individuals of H. platurus can survive in freshwater for at least nine months.13 They do not drink undiluted seawater14, but freshwater that accumulates on the sea surface during heavy rainfall.14 As a result, Pelagic Sea-Snakes in regions of seasonal drought can spend much of their life dehydrated.15

Special thanks to Ellen Smith, our official protector of the Yellow-bellied Sea-Snake, for symbolically adopting this species and helping bring the Reptiles of Galápagos project to life.

At sea, Yellow-bellied Sea-Snakes swim at a speed of 0.3–7.1 km/h, and do so either forward or backward by sideward undulations aided by the laterally compressed body and tail.11,16 Individuals of Hydrophis platurus spend the majority (51–99.9%) of the time diving1 to an average maximum depth of 15 m, although they can dive down to 50 m.1 Pelagic Sea-Snakes can survive submerged for up to 24 h, but single dives last for up to about four hours.1,8 During dives, individuals of H. platurus are able to satisfy 33% of their total oxygen requirement and release 94% of their carbon dioxide by means of gas exchange across their semi-permeable skin.17 Dives are thought to help the snakes regulate their body temperature,8 escape predators,8 avoid sea surface turbulence,18 and possibly detect surface drift lines to join.19 When not diving, the sea snakes float motionless on the surface,20 basking, ambush foraging on pelagic fishes, and drifting passively with surface currents along with floating debris.8,21

When the water temperature is optimal (>25°C),22 the sea snakes can feed. They are specialist float-and-wait predators of small or juvenile surface dwelling fish that seek refuge under the debris, or under the snakes themselves.23–27 Since Yellow-bellied Sea-Snakes are presumed to have poor eyesight,26 they probably use small tactile mechanosensory organs located around their mouth28 to locate fish by the vibrations they produce while moving.29 They seize prey with a laterally directed strike23 and consume it usually without envenomating it.30

Hydrophis platurus is, however, extremely venomous,7 and its neurotoxic venom immobilizes, and is lethal to, fish.4 Despite having the most potent venom (LD50 0.055 mg/kg) among Ecuadorian snakes,31 reports of deaths following bites of H. platurus are rare.7 This is probably related to the snakes' reluctance to bite when in water,12,32 their small (~2 mm in length)33 fangs, and their low average venom yield (0.87–2.8 mg),34–35 which is lower than the estimated 5.9 mg needed to kill a 72 kg person.35 However, human deaths have been reported.7,32,36 Critically envenomated victims die from muscle paralysis that leads to respiratory failure33 within a period of 12–48 h.32,37

In addition to being venomous, individuals of H. platurus are also believed to be poisonous or at least distasteful.30 They have a “warning” coloration and few confirmed predators (pelicans,38 hawks,39 and storks40). They are entirely avoided by native fish,30 picked up and dropped by sea birds,41–43 and regurgitated if taken by marine fish30 and mammals.44 Stranded snakes are scavenged by crabs.45

In areas where mean monthly water temperatures exceed 25°C, Hydrophis platurus breeds throughout the year.5,46 Copulation takes place in water.4 After a gestation period of 6–8 months,4 females “give birth” (the eggs hatch within the mother) in the water to 1–10 young4,11 that are 22–26 cm in total length at birth.4 Females may surround and protect newborns during their first days of life.47

In some populations, as many as 18.9% of the individuals of H. platurus, especially large ones, are colonized by epibionts such as shrimps, crabs, snails, barnacles, hydroids, bryozoans, tunicates, and fish.48,49 As a response, Yellow-bellied Sea-Snakes engage in spontaneous "knotting,"50 a behavior that presumably helps eliminate this fauna as well as help the snake shed (every 9 to 43 days)22 in a substrate-less environment. Snakes of this species are host to a variety of internal parasitic worms.11,51 Captive individuals of the Yellow-bellied Sea-Snake have lived up to 3.5 years.52

Conservation: Least Concern.53 Hydrophis platurus is listed in this category because it is the world's most widely distributed snake species,54 it has presumed stable populations, and is not facing major immediate threats of extinction.53 Instead, with the recent arrival of the species in the Atlantic,55 Hydrophis platurus has the potential to increase its range.56 Minor but confirmed threats to the species include oil spills57 and bycatch in fisheries.53 Another threat faced by the Yellow-bellied Sea-Snake is climate change. Since the species relies on freshwater from rainfall, it could potentially be affected by changing rainfall patterns associated with climate change.

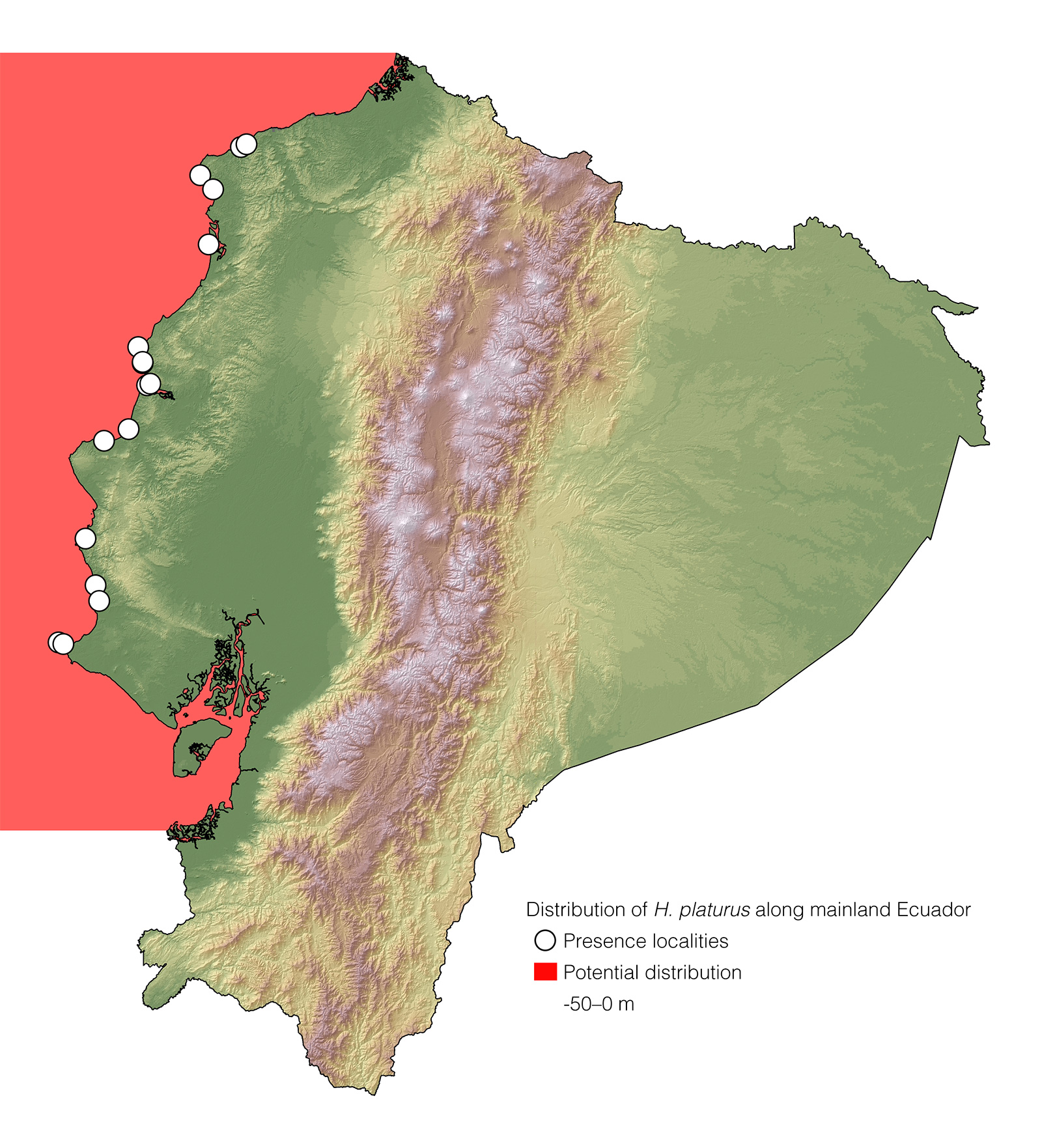

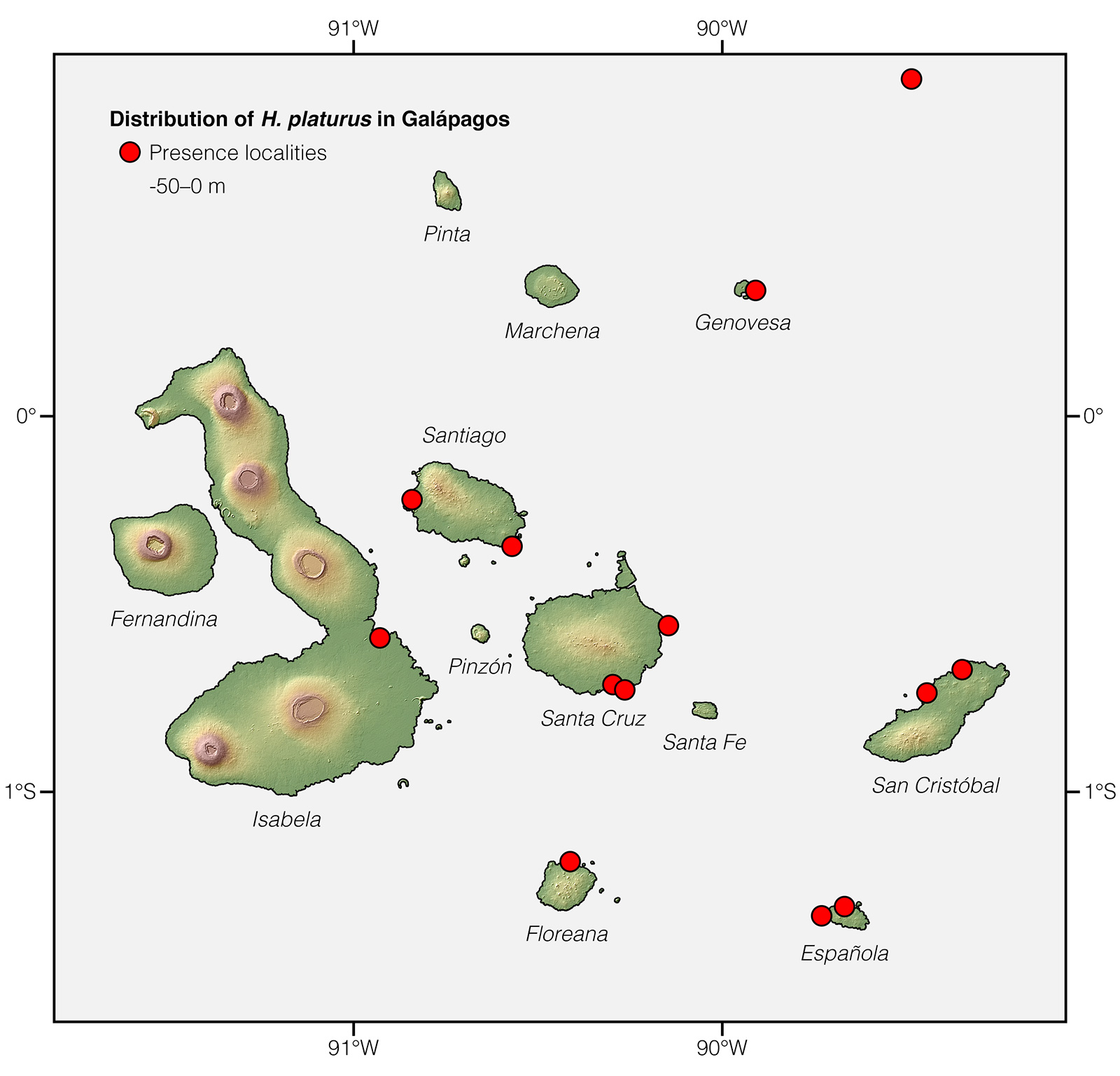

Distribution: The entire tropical Indian and Pacific oceans.7,21 Sightings of Yellow-bellied Sea-Snakes in the Atlantic55 may be the result of snakes passing through the Panama Canal. Records of Hydrophis platurus along the coast of mainland Ecuador and Galápagos are thought to be the result of waif dispersal.5

Etymology: The generic name Hydrophis, which comes from the Greek words hydros (meaning “water”) and ophis (meaning “serpent”),58 refers to the aquatic habits of this genus of snakes. The specific epithet platurus, which comes from the Greek words platys (meaning “flat”) and oura (meaning “tail”),58 refers to the distinctive paddle-shaped tail of the species.

See it in the wild: Pelagic Sea-Snakes cannot be expected to be seen reliably along the coast of mainland Ecuador, since individuals arrive as a result of waif dispersal and are recorded no more than once every few months.

FAQ

Do sea snakes breathe? Yes, much like terrestrial snakes do. Although in some species, like in Hydrophis platurus, the snakes can satisfy 33% of their total oxygen requirement and release 94% of their carbon dioxide by means of gas exchange across their skin.17

Do sea snakes camouflage? Most sea snakes, including the Yellow-bellied Sea-Snake, do the opposite. They have bright colors that act as a warning to potential predators.

Do sea snakes have gills? They don’t, but they can still obtain oxygen and release carbon dioxide while submerged.17

What happens when a Yellow-bellied Sea-Snake bites you? The consequences of being bitten by a Yellow-bellied Sea-Snake varies depending on, among other things, the amount of venom injected and the physical condition of the victim. Sometimes, there may be no noticeable effects at all. On rare occasions, critically envenomated victims may die from muscle paralysis that leads to respiratory failure.33

Where do sea snakes live? The majority of sea snake species are found throughout the Indian Ocean and western Pacific Ocean. Only the Yellow-bellied Sea-Snake occurs in the eastern Pacific and, recently, also in the Caribbean.

Why are sea snakes so venomous? Sea snakes are extremely venomous in order to be 100% efficient in quickly immobilizing fish in the water without risking the prey escaping or struggling.

Author: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

Academic reviewers: Harvey Lillywhite and Coleman Sheehy.

Photographers: Sebastián Di Doménico and Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Arteaga A (2020) Hydrophis platurus. In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com

Literature cited:

- Rubinoff I, Graham JB, Motta J (1986) Diving of the sea snake Pelamis platurus in the Gulf of Panama I. Dive depth and duration. Marine Biology 91: 181–191.

- Myers GS (1945) Nocturnal observations on sea snakes in Bahia Honda, Panama. Herpetologica 3: 22–23.

- Dunson WA, Minton S A (1978) Diversity, distribution, and ecology of Philippine marine snakes (Reptilia, Serpentes). Journal of Herpetology 12: 281–286.

- Savage JM (2002) The amphibians and reptiles of Costa Rica, a herpetofauna between two continents, between two seas. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 934 pp.

- Hecht MK, Kropach C, Hecht BM (1974) Distribution of the yellow-bellied sea snake, Pelamis platurus, and its significance in relation to the fossil record. Herpetologica 30: 387–396.

- Vallarino O, Weldon PJ (1996) Reproduction in the yellow-bellied sea snake (Pelamis platurus) from Panama: field and laboratory observations. Zoo Biology 15: 309–314.

- Campbell JA, Lamar WW (2004) The venomous reptiles of the Western Hemisphere. Cornell University Press, New York, 774 pp.

- Dunson WA, Ehlert GW (1971) Effects of temperature, salinity, and surface water flow on distribution of the sea-snake Pelamis. Limnology and Oceanography 16: 845–853.

- Minton SA (1966) A contribution to the herpetology of West Pakistan. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 134: 27–184.

- Palot MJ, Radhakrishnan C (2010) First record of Yellow-bellied Sea-Snake Pelamis platurus (Linnaeus, 1766) (Reptilia: Hydrophiidae) from a riverine tract in northern Kerala, India. Journal of Threatened Taxa 2: 1175–1176.

- Ernst CH, Ernst EM (2011) Venomous reptiles of the United States, Canada, and Northern Mexico. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 392 pp.

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- Kropach C (1973) A field study of the sea-snake Pelamis platurus (Linnaeus) in the Gulf of Panama. PhD thesis, New York, United States, City University of New York.

- Lillywhite HB, Brischoux F, Sheehy CM, Pfaller JB (2012) Dehydration and drinking responses in a pelagic sea snake. Integrative and Comparative Biology 52: 227–234.

- Lillywhite HB, Sheehy CM, Brischoux F, Grech A (2014) Pelagic sea snakes dehydrate at sea. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B 281: 20140119.

- Rubinoff I, Graham JB, Motta J (1988) Diving of the sea snake Pelamis platurus in the Gulf of Panama II. Horizontal movement patterns. Marine Biology 97: 157–163.

- Graham JB (1974) Aquatic respiration in the sea snake Pelamis platurus. Respiratory Physiology & Neurobiology 21: 1–7.

- Cook TR, Brischoux F (2014) Why does the only 'planktonic tetrapod' dive? Determinants of diving behaviour in a marine ectotherm. Animal Behavior 98: 113–123.

- Brischoux F, Lillywhite HB (2011) Light- and flotsam-dependent ‘float-and-wait’ foraging by pelagic sea snakes (Pelamis platurus). Marine Biology 158: 2343–2347.

- Klauber LM (1935) The feeding habits of a sea snake. Copeia 1935: 182.

- Sheehy III CM, Solórzano A., Pfaller JB, Lillywhite HB (2012) Preliminary insights into the phylogeography of the Yellow-bellied Sea-Snake, Pelamis platurus. Integrative and Comparative Biology 52: 321–330.

- Zeiller W (1969) Maintenance of the Yellowbellied Seasnake, Pelamis platurus, in Captivity. Copeia 1969: 407–408.

- Pickwell GV (1972) Amphibians and reptiles of the Pacific states. Dover Publications, New York, 234 pp.

- Voris HK (1972) The role of sea snakes (Hydrophiidae) in the trophic structure of coastal ocean communities. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of India 14: 429–442.

- Voris HK, Voris HH (1983) Feeding strategies in marine snakes: an analysis of evolutionary, morphological, behavioral, and ecological relationships. American Zoologist 23: 411–425.

- Hibbard E, Lavergne J (1972) Morphology of the retina of the sea-snake Pelamis platurus. Journal of Anatomy 112: 125–136.

- Coleman Sheehy, pers. comm.

- Crowe-Riddell JM, Snelling EP, Watson AP, Suh AK, Partridge JC, Sanders KL (2016) The evolution of scale sensilla in the transition from land to sea in elapid snakes. Open Biology 6: 160054.

- Heatwole H (1987) Sea snakes. Krieger Publishing, Malabar, 148 pp.

- Rubinoff I, Kropach C (1970) Differential reactions of Atlantic and Pacific predators to sea-snakes. Nature 228: 1288–1290.

- Steinhoff S (2018) LD50 of venomous snakes. Available from: http://snakedatabase.org

- Medem F (1969) El desarrollo de la herpetología en Colombia. Revista de la Academia Colombiana de Ciencias Exactas, Físicas y Naturales 13: 149–199.

- Vick JA, Pickwell GV, Shipman WH (1973) Collection, toxicity, and preliminary pharmacology of venom from the sea snake Pelamis platurus. Edgewood Arsenal Technical Report, San Diego, 39 pp.

- Bolaños R, Cerdas L, Taylor RT (1975) Color patterns and venom characteristics in Pelamis platurus. Copeia 1974: 909–912.

- Pickwell GV, Vick JA, Shipman WH, Grenan MM (1972) Production, toxicity, and preliminary pharmacology of venom from the sea snake, Pelamis platurus. In: Worthen LR (Ed) Food-drugs from the sea. Marine Technology Society, Washington, D.C., 247–265.

- Curran CH, Kauffeld C (1937) Snakes and their ways. Harper and Brothers, New York, 285 pp.

- Becke L (1909) Neath Austral Skies. John Milne, London, 315 pp.

- Álvarez-León R, Hernández-Camacho JI (1998) Notas sobre la ocurrencia de Pelamis platurus (Reptilia: Serpentes: Hydrophiidae) en el Pacífico Colombiano. Caldasia 20: 93–102.

- Solórzano A, Sasa M (2017) Hydrophis platura. Predation by a Common Black-Hawk (Buteogallus anthracinus). Mesoamerican Herpetology 4: 431–433.

- Solórzano A, Kastiel T (2015) Hydrophis platurus. Predation by a Wood Stork (Mycteria americana). Mesoamerican Herpetology 2: 121–123.

- Weldon PJ, Vallarino O (1988) Wounds on the Yellow-Bellied Sea Snake (Pelamis platurus) from Panama: evidence of would-be predators? Biotropica 20: 174.

- Reynolds RP, Pickwell GV (1984) Records of the yellow-bellied sea snake, Pelamis platurus, from the Galápagos Islands. Copeia 1984: 786–789.

- Sheehy III CM, Pfaller JB, Lillywhite HB, Heatwole HF (2011) Pelamis platurus. Predation. Herpetological Review 42: 443.

- Heatwole H, Finnie EP (1980) Seal predation on a sea snake. Herpetofauna 11: 24.

- Duellman WE (1961) The amphibians and reptiles of Michoacán, Mexico. Publications of the Museum of Natural History, University of Kansas 15: 205–249.

- Kropach C (1975) The yellow-bellied sea snake, Pelamis, in the eastern Pacific. In: Dunson WA (Ed) The biology of sea snakes. University Park Press, Baltimore, 185–213.

- Rose W (1950) The reptiles and amphibians of southern Africa. Maskew Miller, Cape Town, 388 pp.

- Pfaller JB, Frick MG, Brischoux F, Sheehy CM, Lillywhite HB (2012) Marine snake epibiosis: a review and first report of decapods associated with Pelamis platurus. Integrative and Comparative Biology 52: 296–310.

- Kropach C, Soule JD (1973) An unusual association between an ectoproct and a sea snake. Herpetologica 29: 17–19.

- Pickwell GV (1971) Knotting and coiling behavior in the pelagic sea snake Pelamis platurus (L.). Copeia 1971: 348–350.

- Sprent JFA (1988) Ascaridoid nematodes of amphibians and reptiles: Ophidascaris Baylis, 1920. Systematic Parasitology 11: 165–213.

- Snider AT, Bowler JK (1992) Longevity of reptiles and amphibians in North American collections. Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles, Herpetological Circular. 21: 1–40.

- Guinea M, Lukoschek V, Cogger H, Rasmussen A, Murphy J, Lane A, Sanders K, Lobo A, Gatus J, Limpus C, Milton D, Courtney T, Read M, Fletcher E, Marsh D, White MD, Heatwole H, Alcala A, Voris H, Karns D (2017) Hydrophis platurus. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org

- Pickwell GV, Culotta WA (1980) Pelamis, P. platurus. Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles 255: 1–4.

- Hernández-Camacho JI, Alvarez-León R, Renjifo-Rey JM (2006) Pelagic sea snake Pelamis platurus (Linnaeus, 1766) (Reptilia: Serpentes: Hydrophiidae) is found on the Caribbean coast of Colombia. Memoria de la Fundación La Salle de Ciencias Naturales 164: 7–16.

- Graham JB, Rubinoff I, Hecht MK (1971) Temperature physiology of the sea snake Pelamis platurus: an index of its colonization potential in the Atlantic Ocean. PNAS 68: 1360–1363.

- Jernelöv A, Linden O (1983) The effects of oil pollution on mangrove and fisheries in Ecuador and Colombia. In: Teas HJ (Ed) Biology and ecology of mangroves. Dr. W. Junk Publishers, The Hague, 185–188.

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington, 882 pp.