Published June 27, 2019. Updated January 7, 2024. Open access. Peer-reviewed. | Purchase book ❯ |

Shieldhead Gecko (Gonatodes caudiscutatus)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Sauria | Sphaerodactylidae | Gonatodes caudiscutatus

English common name: Shieldhead Gecko.

Spanish common names: Geco cabeciamarillo, salamanquesa cabeciamarilla.

Recognition: ♂♂ 9.4 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=4.4 cm. ♀♀ 9.6 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=4.5 cm..1,2 Geckos of the genus Gonatodes in Ecuador can be identified based on their diurnal habits, lack of movable eyelids, undilated digits having exposed claws, and absence of a scaly supraciliary flap (present in Lepidoblepharis).3,4 Shieldhead Geckos differ from the two other Gonatodes in Ecuador by having a posthumeral ocellus and lacking dorsal vermiculations (Fig. 1).1 Males of G. caudiscutatus can be identified based on their distinctive head coloration: bright yellow to orange with contrasting dark brown to black reticulations (Fig. 1).2 Females and juveniles are brownish overall and similar to other Ecuadorian dwarf geckos, but they are unique in lacking enlarged scales above the upper eyelid and a vertical white line above the shoulder.1,2

Figure 1: Individuals of Gonatodes caudiscutatus from Ecuador: Yankuam Lodge, Zamora Chinchipe province (); Reserva Las Balsas, Santa Elena province (); Huella Verde Lodge, Pastaza province (). j=juvenile.

Natural history: Gonatodes caudiscutatus is an opportunistic gecko that naturally occurs in areas of seasonally dry forest and rainforests, but also colonizes and occurs in high densities in human-modified environments such as crops, planted forests, and peri-urban areas.5–7 Shieldhead Geckos are diurnal and most active during the middle of the day.2 They are gregarious, being found in groups, basking or foraging on tree trunks, buttress roots, walls, and on timber.2,5 At night, they remain hidden within crevices or under piles of timber, trash, and debris.2 In the presence of a disturbance, these jittery lizards tend flee into crevices or under surface objects. If captured, they may shed the tail and lose portions of the skin.2 Shieldhead Geckos feed on termites, beetles, bees, and wasps.2 Females lay clutches of a single egg at intervals of about three weeks.2 These hatch after 90–110 days.2

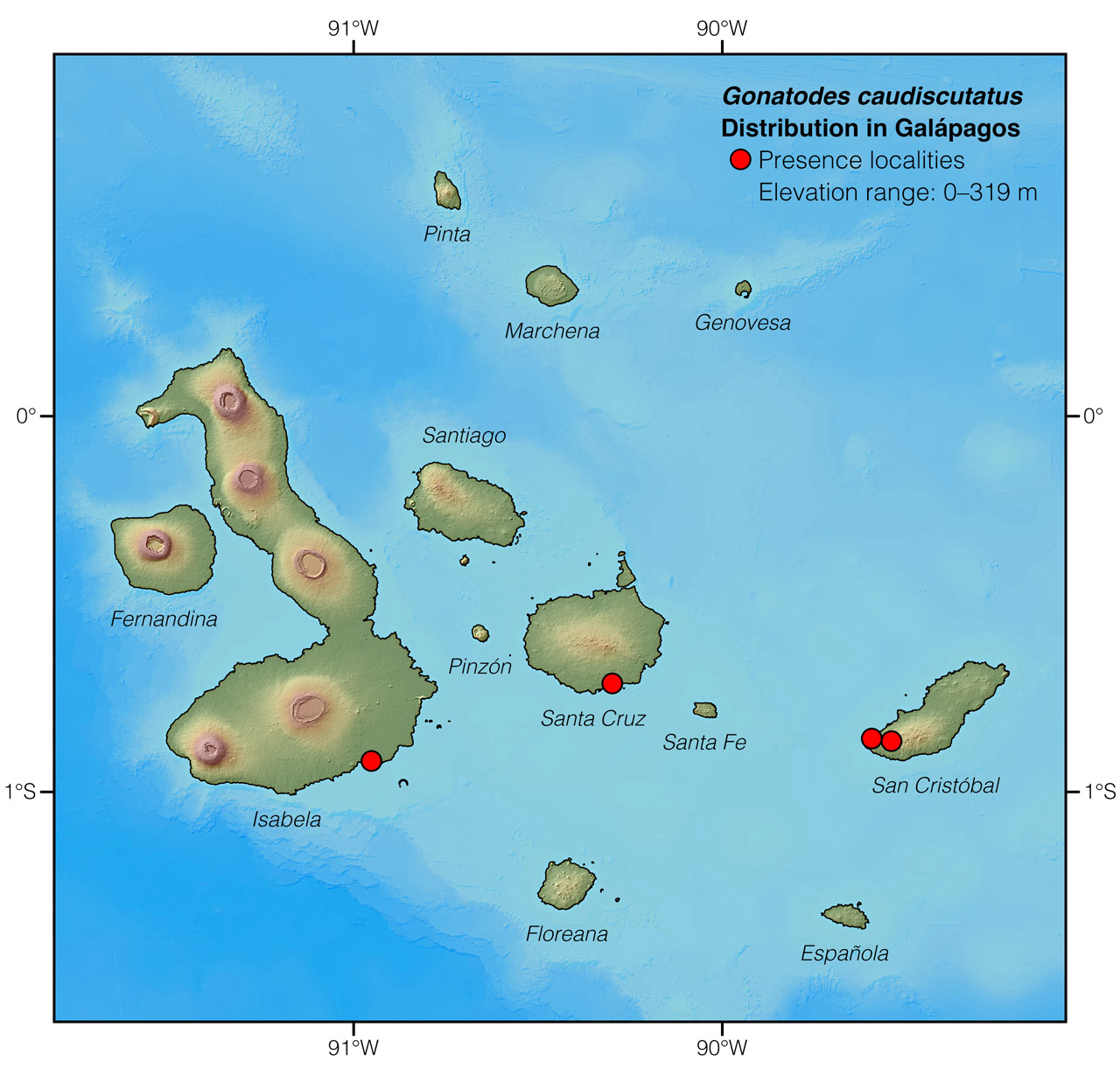

Conservation: Least Concern Believed to be safe from extinction given current circumstances..8 Gonatodes caudiscutatus is listed in this category because this species is widely distributed, thrives in human-modified environments, and is considered to be undergoing no obvious population declines nor facing major immediate threats of extinction.8 Conversely, G. caudiscutatus is an introduced species in the Galápagos Islands6 and the Amazonian slopes of the Andes in Ecuador.5 There is no information regarding how the introduced Shieldhead Gecko interacts with endemic species in Galápagos, but, since it seems to depend on human-modified environments, its impact might be limited.2

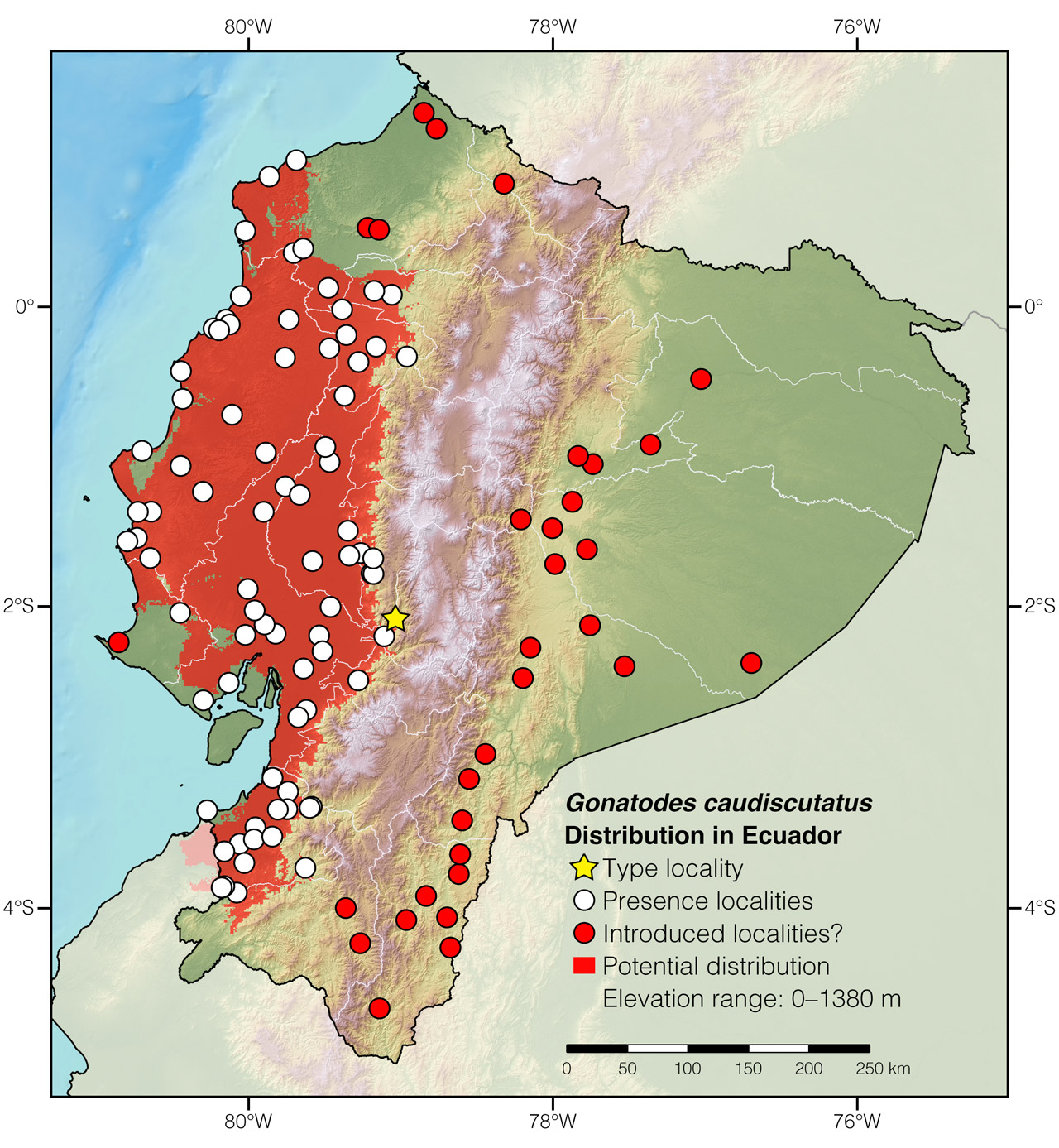

Distribution: Gonatodes caudiscutatus is native to the Pacific lowlands of Ecuador and northwestern Perú (Fig. 2), and has been introduced to Amazonian Ecuador and the Galápagos (Fig. 3).2

Figure 2: Distribution of Gonatodes caudiscutatus in Ecuador. The star corresponds to the type locality: Pallatanga, Chimborazo province. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Figure 3: Distribution of Gonatodes caudiscutatus in Galápagos. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The generic name Gonatodes comes from the Greek words gonatos (=node) and odes (=resembling),9 and probably refers to the form of the digits which are slender but in which the joints are prominent as swellings.10 The specific epithet caudiscutatus means “shielded tail” in Latin.9

See it in the wild: On mainland Ecuador, the easiest place to see individuals of Gonatodes caudiscutatus is the town of Puerto Quito, Pichincha province. In Galápagos, the town El Progreso, on San Cristóbal Island, is notable for having high densities of Shieldhead Geckos.

Special thanks to Anna Kay Smith for symbolically adopting the Shieldhead Gecko and helping bring the Reptiles of Ecuador book project to life.

Click here to adopt a species.

Authors: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador. and Juan M GuayasaminbAffiliation: Universidad San Francisco de Quito, Quito, Ecuador.

Academic reviewer: Anthony RussellcAffiliation: The University of Calgary, Canada.

Photographer: Jose VieiradAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,eAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Arteaga A, Guayasamin JM (2024) Shieldhead Gecko (Gonatodes caudiscutatus). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/EOMY5868

Literature cited:

- Sturaro MJ, Avila-Pires TCS (2013) Redescription of the gecko Gonatodes caudiscutatus (Günther, 1859) (Squamata: Sphaerodactylidae). South American Journal of Herpetology 8: 132–145. DOI: 10.2994/SAJH-D-13-00002.1

- Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J, Tapia W, Guayasamin JM (2019) Reptiles of the Galápagos: life on the Enchanted Islands. Tropical Herping, Quito, 208 pp. DOI: 10.47051/AQJU7348

- Vanzolini PE (1968) Geography of the South American Gekkonidae. Arquivos de Zoologia 17: 85–112.

- Sturaro MJ, Avila-Pires TCS (2011) Taxonomic revision of the geckos of the Gonatodes concinnatus complex (Squamata: Sphaerodactylidae), with description of two new species. Zootaxa 2869: 1–36. DOI: 10.11646/zootaxa.2869.1.1

- Carvajal-Campos A, Torres-Carvajal O (2012) Gonatodes caudiscutatus (Günther, 1859) (Squamata: Sphaerodactylidae): Distribution extension in Ecuador. Check List 8: 525–527. DOI: 10.15560/8.3.525

- Olmedo J, Cayot L (1994) Introduced geckos in the towns of Santa Cruz, San Cristóbal and Isabela. Noticias de Galápagos 53: 7–12.

- Valencia JH, Garzón K (2011) Guía de anfibios y reptiles en ambientes cercanos a las estaciones del OCP. Fundación Herpetológica Gustavo Orcés, Quito, 268 pp.

- Caicedo J, Calderón M, Castro F, Ines Hladki A, Kornacker P, Ramírez Pinilla M, Renjifo J, Urbina N (2016) Gonatodes caudiscutatus. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org. DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T178422A44954082.en

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington D.C., 882 pp.

- Russell AP, Baskerville J, Gamble T, Higham TE (2015) The evolution of digit form in Gonatodes (Gekkota: Sphaerodactylidae) and its bearing on the transition from frictional to adhesive contact in Gekkotans. Journal of Morphology 276: 1311–1132. DOI: 10.1002/jmor.20420

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Gonatodes caudiscutatus in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used. Asterisk (*) indicates type locality.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Ecuador | Azuay | Sarayunga | Photo by José Manuel Falcón |

| Ecuador | Azuay | Uzhcurumi | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Bolívar | Balzapamba | AMNH 38767; examined |

| Ecuador | Bolívar | Cabañas del Camino Real | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Bolívar | Caluma | Altamirano-Ponce et al. 2023 |

| Ecuador | Bolívar | Telimbela | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Cañar | El Chorro | Photo by Alex Angulo |

| Ecuador | Carchi | Chinambí | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Chimborazo | Pallatanga* | Günther 1859 |

| Ecuador | El Oro | Arenillas | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | El Oro | Cascadas de Manuel | Garzón-Santomaro et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | El Oro | Pasaje, 3 km E of | AMNH 110593; examined |

| Ecuador | El Oro | Portovelo | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | El Oro | Reserva Militar Arenillas | Garzón-Santomaro et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | El Oro | San Gregorio | Garzón-Santomaro et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | El Oro | Santa Lucía, 3 km W of | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | El Oro | Santa Rosa | AMNH 22236; examined |

| Ecuador | El Oro | Santa Rosa, 6 mi S of | Sturaro & Avila-Pires 2013 |

| Ecuador | El Oro | Tendales | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | El Oro | Valle Hermoso | Pazmiño-Otamendi & Carvajal-Campos 2020 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Atacames | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Bilsa Biological Reserve | USNM 541949; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Bosque Protector La Perla | Photo by Nathan Shepard |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Canandé Biological Reserve | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Hacienda Cucaracha | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Itapoa Reserve | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Mompiche | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | San Lorenzo | Online multimedia |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Terminal Marítimo OCP | Valencia & Garzón 2011 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Tundaloma Lodge | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Y de la Laguna | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | El Progreso | Lever 2003 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Puerto Ayora | Jiménez-Uzcátegui 2014 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Puerto Baquerizo Moreno | Arteaga et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Puerto Villamil | Arteaga et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | San Cristóbal | Arteaga et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Balzar | Sturaro & Avila-Pires 2013 |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Bosque Protector Cerro Blanco | Almendáriz & Carr 2007 |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Bucay | AMNH 21906; examined |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Cerro Masvale | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Durán | UF 87643; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Guayas | El Empalme, 21 km SW of | Sturaro & Avila-Pires 2013 |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Hacienda San Miguel | Sturaro & Avila-Pires 2013 |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Isla Palo Santo | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Montero, 14 Km ESE of | KU 142674; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Naranjal | GBIF |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Nueva Unión Campesina | Pazmiño-Otamendi & Carvajal-Campos 2020 |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Parque Samanes | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Pasaje | GBIF |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Puerto del Morro | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Río Daule | UF 86871; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Guayas | San Fernando | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Zoo El Pantanal | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Loja | Bosque Petrificado Puyango | Garzón-Santomaro et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Loja | Catamayo | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Loja | Malacatos | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Los Ríos | Bosque Protector Pedro Franco Dávila | Cruz & Sánchez 2016 |

| Ecuador | Los Ríos | Centro Científico Río Palenque | Sturaro & Avila-Pires 2013 |

| Ecuador | Los Ríos | Cerro Samama Mumbes | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Los Ríos | Finca Elba | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Los Ríos | Quevedo | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Los Ríos | Quevedo, 4 km N of | KU 132467; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Los Ríos | Recinto Naranjo Agrio Alto | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Agua Blanca | Altamirano-Ponce et al. 2023 |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Boca de Palmito | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Bosque Seco Lalo Loor | Hamilton et al. 2005 |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Cañales, 3 km W of | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Cerro Puca | USNM 166151; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Chone | Sturaro et al. 2011 |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Don Juan | Hamilton et al. 2005 |

| Ecuador | Manabí | El Carmen | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Manabí | La Crespa | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Manta | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Pedernales | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Portoviejo | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Puerto Cayo, 2 Km E of | Sturaro et al. 2011 |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Puerto López | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Reserva Biológica Cerro Seco | Photo by Michi Maissen |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Reserva Jama Coaque | Lynch et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Río Ayampe | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Ruta Spondylus | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Tito Santos | Hamilton et al. 2005 |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Villa Ramonita | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Estación Biológica Wisui | Chaparro et al 2011 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Gualaquiza | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Limón | Pazmiño-Otamendi & Carvajal-Campos 2020 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Palora | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Pindal | Photo by Jorge Vaca |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Proaño | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Siete Iglesias Reserve | Online multimedia |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Sucúa | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Taisha | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Napo | Chontapunta | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Napo | Selina Napo | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Napo | Tena | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Coca | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Chichirota | Sturaro & Avila-Pires 2013 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Huella Verde Lodge | This work; Fig. 1 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Punin | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Puyo | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Pedro Vicente Maldonado | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Rancho Suamox | Photo by Rafael Ferro |

| Ecuador | Santa Elena | Reserva Las Balsas | This work; Fig. 1 |

| Ecuador | Santa Elena | Santa Elena | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Santo Domingo de los Tsáchilas | El Triunfo | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Santo Domingo de los Tsáchilas | Finca La Floreana | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Santo Domingo de los Tsáchilas | Otongachi | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Santo Domingo de los Tsáchilas | Santo Domingo | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Tungurahua | Río Negro | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | El Pangui | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Guayzimi | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Palanda | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Panguintza | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Yankuam Lodge | This work; Fig. 1 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Zamora | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Perú | Tumbes | Cabo Cotrina | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Perú | Tumbes | Destacamento Campoverde | iNaturalist; photo examined |