Published September 11, 2021. Updated January 25, 2025. Open access. | Purchase book ❯ |

Rainbow Galliwasp (Diploglossus monotropis)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Sauria | Diploglossidae | Diploglossus monotropis

English common names: Rainbow Galliwasp, Orange-bellied Galliwasp, Costa Rican Rainbow Striped Galliwasp.

Spanish common names: Escorpión, escorpión coral (Ecuador, Costa Rica, Panama); mamá culebra, mamá coral, madre de culebra (Colombia, Panama).

Recognition: ♂♂ 53.5 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=21.5 cm. ♀♀ 42.8 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=18.8 cm..1 The Rainbow Galliwasp (Diploglossus monotropis) is immediately identifiable from other Chocoan lizards by its cycloid (similar to fish scales) slightly keeled dorsal scales and its unique coloration.1,2 The dorsal pattern consists of a dark background color with red to bright yellow or white bands,1,3 although there are specimens with an almost uniform coloration (Fig. 1).2,4 The ventral coloration is bright yellow or red and the head is reddish to bright yellow. This species undergoes an ontogenetic change in its coloration: juveniles are black with thin white stripes all over the body and tail, with an orange to red belly, orange to red flanks, and a bright red to orange head.2–5 Males differ from females by their larger body size and by having a much brighter head coloration.1,4

Figure 1: Individuals of Diploglossus monotropis: Centro Científico Río Palenque, Los Ríos province, Ecuador (); Morromico Lodge, Chocó department, Colombia (). j=juvenile.

Natural history: Diploglossus monotropis is a rarely seen inhabitant of the Chocó biome, occurring in old-growth rainforest, forest edge,6 or in secondary forest, cacao plantations,7 disturbed areas, and rural gardens.2,4 It is a primarily diurnal and semi-fossorial lizard that spends most of its time in burrows (probably built by other animals), under logs or rocks,7 in leaf-litter, and among roots of trees and palms (Iriartea sp.).3,4 Nocturnal activity has also been recorded.7 Rainbow Galliwasps can rarely be seen sunbathing or foraging on the ground.3,4 Their diet includes invertebrates such as insects, crabs, and snails.3 In captivity, individuals can also feed on mice.4,8

In the presence of a disturbance, Rainbow Galliwasps usually escape by retreating into holes, sliding between the roots, or burying themselves.3,4 A juvenile ran into the water and remained submerged for approximately three minutes.4 If the threat persists, individuals open the mouth aggressively and are capable of providing strong bites.4 They are also quick to shed the tail, but it does not regenerate completely.9 It seems that the bright coloration mimics that of a true coral snake. Juveniles are similar to the coral snake Micrurus mipartitus. There are records of raptors, sunbitterns (Eurypyga helias),10 snakes, and mammals preying upon individuals of Diploglossus monotropis.3 The helminth Cruzia mexicana has been found in the intestine of D. monotropis.11

In some areas of the Chocó biome, locals know this species as mamá culebra, which means “mother of snakes,” or mamá coral, which means “mother of coral snakes.” There is a belief that this reptile gives birth to coral snakes and therefore is venomous. In Ecuador, the common name is escorpión (=scorpion) and probably refers to the fact that the lizard is thought to sting with the tail. Despite the widespread belief that it is a venomous lizard, it is in fact totally harmless to humans.3

Diploglossus monotropis is an oviparous species that seems to have maternal care.12,13 In captivity, a female was coiled around her clutch and became defensive when the eggs were tried to be removed.12

Conservation: Least Concern Believed to be safe from extinction given current circumstances..14–16 Diploglossus monotropis is included in this category because the species is widely distributed, especially in areas that have not been heavily affected by deforestation, such as the Colombian Pacific coast. As a result, the species is unlikely to be declining fast enough to qualify for a more threatened category.14 Since it is a secretive reptile, its population dynamics are uncertain, but there are presumably enough suitable habitats throughout the distribution of the species to ensure its survival.14 Unfortunately, forest destruction, poaching for the pet trade, and the indiscriminate killing by the hands of local people could pose a threat to the survival of some populations.

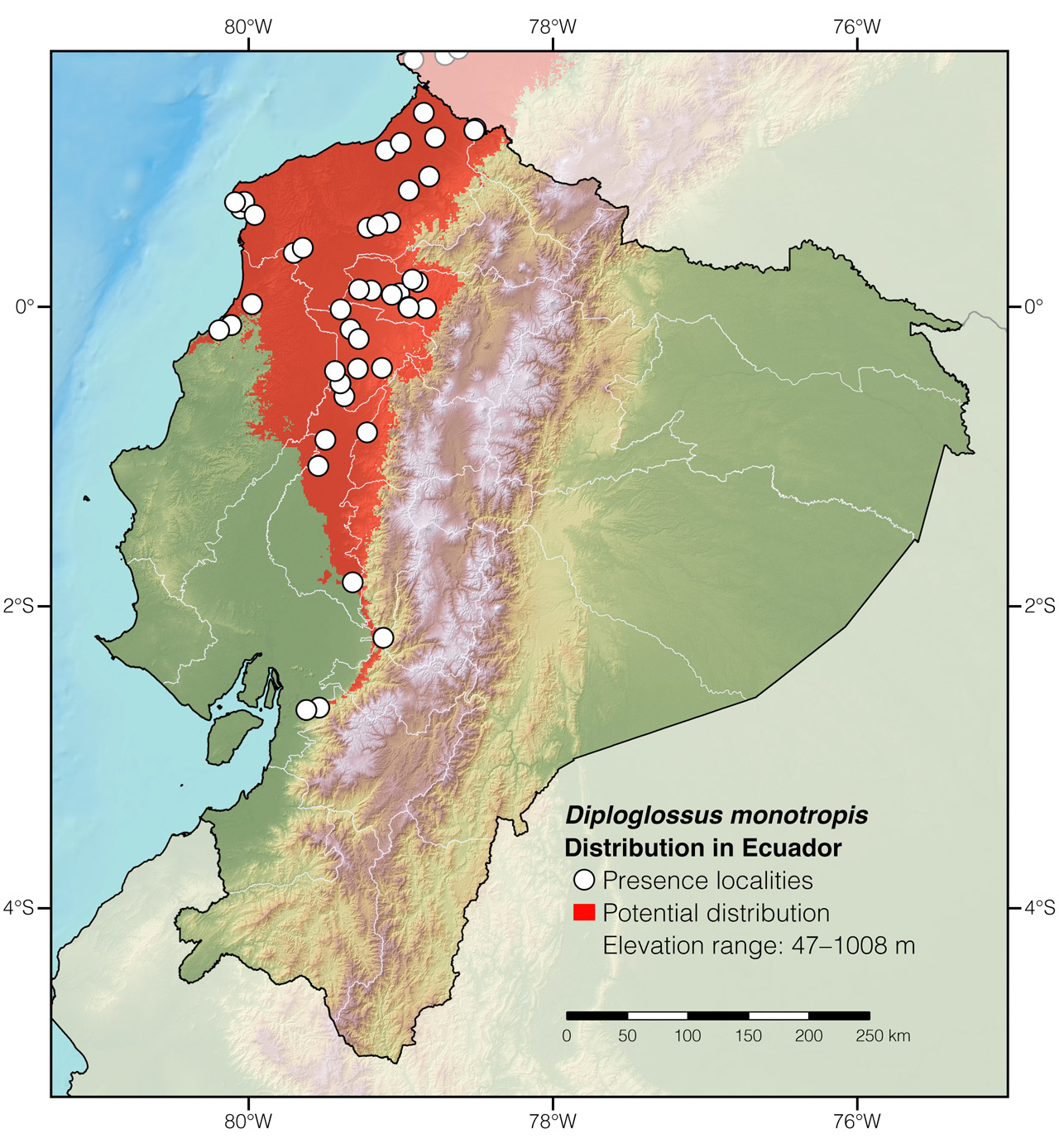

Distribution: Diploglossus monotropis is widely distributed throughout the lowlands of Mesoamerica, the Chocó, and Río Magdalena valley regions. The species occurs in the Atlantic lowlands of Nicaragua and Costa Rica, in both Atlantic and Pacific versants in Panama and Colombia, and in western Ecuador. In Ecuador, this lizard has been recorded at elevations ranging between 47 and 1008 m (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Distribution of Diploglossus monotropis in Ecuador. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map. The type locality is not included as it is unknown.

Etymology: The generic name Diploglossus, which comes from the Greek words diploos (meaning “twofold”) and glossa (=tongue),17 probably refers to the bifid tongue in lizards of this genus. The specific epithet monotropis, which comes from the Greek words monos (meaning “single” or “alone”) and tropis (meaning “ridge”),17 probably refers to the keeled dorsal scales, a characteristic mentioned in the original description of the species.18

See it in the wild: Rainbow Galliwasps are rarely seen in Ecuador, but one way to increase the odds of finding an individual is by walking along forest trails during the day and paying close attention to holes at the base of trees or in thick accumulations of logs and stones. Also, individuals may be found by turning over rocks and logs or raking leaf-litter in the forest. In Ecuador, the localities having the greatest number of recent observations of Diploglossus monotropis are Canandé Reserve, Itapoa Reserve, Bilsa Biological Reserve, and the Río Palenque Scientific Station.

Acknowledgments: Special thanks to Quetzal Dwyer for providing ecological data on this species and to Pablo Montoya for providing field assistance to find and photograph this species in Morromico, Colombia.

Special thanks to Meredith Swartwout for symbolically adopting the Rainbow Galliwasp and helping bring the Reptiles of Ecuador book project to life.

Click here to adopt a species.

Author: Jose VieiraaAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,bAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador.

Editor: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

Photographers: Jose VieiraaAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,bAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador. and Sebastián Di DoménicocAffiliation: Keeping Nature, Bogotá, Colombia.

How to cite? Vieira J (2021) Rainbow Galliwasp (Diploglossus monotropis). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/PATH3112

Literature cited:

- Savage JM (2002) The amphibians and reptiles of Costa Rica, a herpetofauna between two continents, between two seas. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 934 pp.

- Myers CW (1973) Anguid lizards of the genus Diploglossus in Panama, with the description of a new species. American Museum Novitates 2523: 1–20.

- Leenders T (2019) Reptiles of Costa Rica: a field guide. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, 625 pp.

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- Barbour T (1923) Notes on reptiles and amphibians from Panama. Occasional Papers of the Museum of Zoology, University of Michigan 129: 1–16.

- Taylor EH (1956) A review of the lizards of Costa Rica. The University of Kansas Science Bulletin 38: 3–322.

- Díaz-Ayala RF, Gutiérrez-Cárdenas PDA, Vásquez-Correa AM, Caicedo-Portilla JR (2015) New records of Diploglossus monotropis (Kuhl, 1820) (Squamata: Anguidae) from Urabá and Magdalena River valley, Colombia, with an updated geographic distribution map. Check List 11: 1–7. DOI: 10.15560/11.4.1703

- Quetzal Dwyer, pers. comm.

- Bochaton C, De Buffrenil V, Lemoine M, Bailon S, Ineich I (2015) Body location and tail regeneration effects on osteoderms morphology—are they useful tools for systematic, paleontology, and skeletochronology in diploglossine lizards (Squamata, Anguidae)? Journal of Morphology 276: 1333–1344.

- Acosta-Chaves V, Salazar Zuñiga JA (2013) Diploglossus monotropis (Costa Rican Rainbow Striped Galliwasp): predation. Herpetological Review 44: 508.

- Bursey CR, Goldberg SR, Telford SR (2007) Gastrointestinal helminths of 14 species of lizards from Panama with descriptions of five new species. Comparative Parasitology 74: 108–140. DOI: 10.1654/4228.1

- Greene HW, Sigala Rodríguez JJ, Powell BJ (2006) Parental behavior in anguid lizards. South American Journal of Herpetology 1: 9–19. DOI: 10.2994/1808-9798(2006)1[9:PBIAL]2.0.CO;2

- Solórzano A (2001) Great fire lizard. Fauna 2: 8–12.

- Acosta Chaves V, Batista A, García Rodríguez A, Vargas Álvarez J, Renjifo J, Cisneros-Heredia DF (2016) Diploglossus monotropis. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org. DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T203042A2759076.en

- Reyes-Puig C (2015) Un método integrativo para evaluar el estado de conservación de las especies y su aplicación a los reptiles del Ecuador. MSc thesis, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador, 73 pp.

- Morales-Betancourt MA, Lasso CA, Páez VP, Bock BC (2005) Libro rojo de reptiles de Colombia. Instituto de Investigación de Recursos Biológicos Alexander von Humboldt, Bogotá, 257 pp.

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington D.C., 882 pp.

- Kuhl H (1820) Beiträge zur Zoologie und vergleichenden Anatomie. Hermannsche Buchhandlung, Frankfurt, 152 pp.

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Diploglossus monotropis in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Colombia | Cauca | ProAves Reserve in Timbiquí | iNaturalist |

| Colombia | Nariño | Bajo Cumilinche | UPTC 011 |

| Colombia | Nariño | Dirección General Marítima (DIMAR) | Pinto-Erazo et al. 2020 |

| Colombia | Nariño | Estero San Antonio | Díaz-Ayala et al. 2015 |

| Colombia | Nariño | Río Rosario | Díaz-Ayala et al. 2015 |

| Ecuador | Carchi | Destacamento Militar | DHMECN 8066 |

| Ecuador | Cotopaxi | Bosque Privado El Jardín de los Sueños | Photo by Christophe Pellet |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Bilsa Biological Reserve | Ortega-Andrade et al. 2010 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | El Aguacate | Vázquez et al. 2005 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Monte Saíno | DHMECN 2888 |

| Ecuador | Azuay | Flor y Selva | MZUA.RE.0069 |

| Ecuador | Carchi | Tobar Donoso | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Chimborazo | San José de Chimbo | AMNH 17667 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Anchayacu | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Borbón | NHMUK 1902.5.27.17-18 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Caimito | This work |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Canandé Reserve | This work |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Carondelet | NHMUK 1901.6.27.4 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Gualpí | This work |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Las Mareas | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Playa de Oro | USNM 20609 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Reserva Tesoro Escondido | Photo by Simon Maddock |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | San Lorenzo | USNM 524936 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Y de la Laguna de Cube | Ítalo Tapia, pers. comm. |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Zapallo Grande | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Naranjal | Field notes of Giovanni Onore |

| Ecuador | Los Ríos | AGROPESA | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Los Ríos | Buena Fé | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Los Ríos | Centro Científico Río Palenque | This work |

| Ecuador | Los Ríos | Luz de America | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Los Ríos | Río Macul | USNM 196935 |

| Ecuador | Los Ríos | San Javier | NHMUK 1901.3.29.23 |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Cerro Pata de Pajaro | This work |

| Ecuador | Manabí | El Carmen | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Jama Coaque Reserve | Wendt & Lynch 2016 |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Jama Coaque Reserve, 1.2 km SE of | GSU 25466 |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Reserva Tito Santos | This work |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Andoas, 1.5 km N of | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Hostería Selva Virgen | This work |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Kapari Lodge | Photo by Francisco Sornoza |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Mashpi Reserve | This work |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Mindo, environs of | This work |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Pedro Vicente Maldonado | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Puerto Quito | MCZ 164508 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Reserva Mashpi Shungo | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | San Miguel de los Bancos | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Santa Elena | La Libertad | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Santo Domingo de los Tsáchilas | Río Baba | UIMNH 80454 |

| Ecuador | Santo Domingo de los Tsáchilas | San Jacinto del Buá | Photo by Miguel Chica |

| Ecuador | Santo Domingo de los Tsáchilas | Bombolí | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Santo Domingo de los Tsáchilas | Bosque Protector La Perla | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Santo Domingo de los Tsáchilas | Julio Moreno, 11 km SE of | iNaturalist |