Published March 15, 2024. Open access. | Purchase book ❯ |

Emerald Palmsnake (Chlorosoma viridissimum)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Serpentes | Colubridae | Chlorosoma viridissimum

English common names: Emerald Palmsnake, Green Palmsnake, Common Green Racer.

Spanish common names: Culebra palmera, corredora verde común.

Recognition: ♂♂ 119.5 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=88.0 cm. ♀♀ 137.6 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=101 cm..1–3 Chlorosoma viridissimum can be distinguished from most Amazonian snakes by being uniformly green dorsally and ventrally (Fig. 1), having a round pupil, and presenting dorsal scales arranged in 19 rows at mid-body.2–6 This species is frequently confused with Erythrolamprus typhlus and with the juveniles of Chironius scurrula. From the former, it differs by having a green belly (instad of white) and from the latter by having 19 rows of dorsal scales at mid-body (instead of 10).2,7,8

Figure 1: Adult male of Chlorosoma viridissimum from Loreto department, Perú.

Natural history: Chlorosoma viridissimum is a rarely seen arboreal and diurnal snake that inhabits primary and secondary rainforests, which can be terra-firme or seasonally flooded.5,9,10 The species also occurs in savannas and forest edge situations.2,5,7,11 During the day, Emerald Palmsnakes are active on the upper forest stratum as well as on logs, shrubs, and on the ground.2–12 At night, they roost on understory vegetation.13,14 Their diet as juveniles consists of lizards (including Hemidactylus mabouia14) and frogs.5,10 As adults, they also consume squirrels14 and bats.15 The Emerald Palmsnake, when disturbed, can exhibit an aggressive display which consists of laterally compressing the anterior third of the body in an S-shaped spiral with the mouth open.5,12,16 This species is opisthoglyphous, meaning it has enlarged grooved teeth towards the rear of the maxilla and is mildly venomous.2 Symptoms of envenomation in humans include swelling, local pain, bleeding from the bite site, vomiting, and headache.2,17–19 A severe case of envenomation resulted in compartmental syndrome, fasciotomy, and debridement, leading to a somewhat deformed arm with reduced use.18 Nesting in C. viridissimum occurs at ground level, including in ant mounds.1,5 Clutches range from 5 to 9 eggs and the incubation period is 77–80 days.1,7

Conservation: Least Concern Believed to be safe from extinction given current circumstances..20 Chlorosoma viridissimum is listed in this category primarily because the species is widely distributed, occurs in protected areas, and is able to tolerate some degree of habitat disturbance so long as forest remain.20

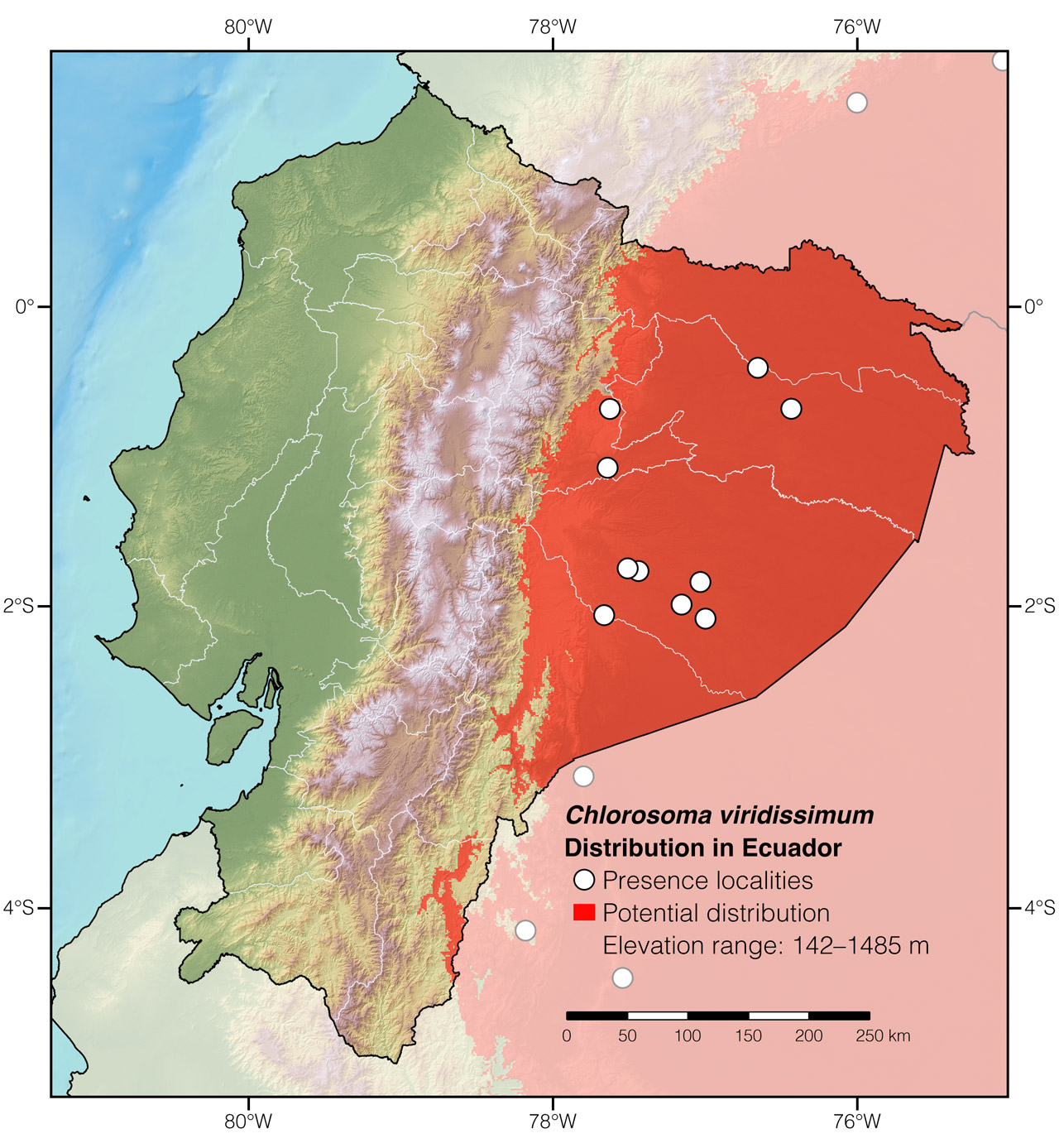

Distribution: Chlorosoma viridissimum is widespread throughout the Amazon rainforest Brazil, Peru, Ecuador (Fig. 2), Colombia, Suriname, Guyana, French Guyana and Venezuela.

Figure 2: Distribution of Chlorosoma viridissimum in Ecuador. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The name Chlorosoma comes from the Greek words chloros (=bright green) and soma (=body).22 The specific epithet viridissimum comes from the Latin viridis (=green) and the suffix -issimus (=very).22

See it in the wild: In Ecuador, Emerald Palmsnakes are found at a rate of about once every few decades. The locality having the greatest number of recent observations is Yasuní Scientific Station.

Authors: Laura C. Martínez-Chico,aAffiliation: Universidad de los Llanos. Villavicencio, Colombia. Juan Acosta-Ortiz,bAffiliation: Universidad de los Llanos. Villavicencio, Colombia. and Andrés F. Aponte-GutiérrezcAffiliation: Grupo de Biodiversidad y Recursos Genéticos, Instituto de Genética, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá, Colombia.,dAffiliation: Fundación Biodiversa Colombia, Bogotá, Colombia.

Editor: Alejandro ArteagaeAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

Photographer: Max BenitofAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Martínez-Chico L, Acosta-Ortiz J, Aponte-Gutiérrez A (2024) Emerald Palmsnake (Chlorosoma viridissimum). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/BBBU5830

Literature cited:

- Rivera D, Aguayo R, Alfaro F (2009) Sobre la puesta, incubación de huevos, nacimiento y desarrollo de crías de Philodryas viridissima (colubridae: xenodontinae) en cautiverio. Cuaderno Herpetológico 23: 51–54.

- Duellman WE (2005) Cusco amazónico: the lives of amphibians and reptiles in an Amazonian rainforest. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, 433 pp.

- Beebe W (1946) Field notes on the snakes of Kartabo, British Guiana, and Caripito, Venezuela. Zoologica 31: 11–52.

- Natera-Mumaw M, Esqueda-González LF, Castelaín-Fernández M (2015) Atlas serpientes de Venezuela. Dimacofi Negocios Avanzados S.A., Santiago de Chile, 456 pp.

- Martins M, Oliveira ME (1998) Natural history of snakes in forests of the Manaus region, Central Amazonia, Brazil. Herpetological Natural History 6: 78–150.

- Entiauspe O, Abegg AD, Rocha AM, Loebmann D (2018) Connecting the dots: filling distribution gaps of Philodryas viridissima (Serpentes: Dipsadidae) in Brazil, with a new state record to Roraima. Herpetology Notes 11: 697–702.

- Starace F (1998) Serpents et amphisbènes de Guyane Française. Ibis Rouge Editions, Guadeloupe, 450 pp.

- Pérez-Santos C, Moreno AG (1988) Ofidios de Colombia. Museo Regionale di Scienze Naturali, Torino, 517 pp.

- Dixon JR, Soini P (1986) The reptiles of the upper Amazon Basin, Iquitos region, Peru. Milwaukee Public Museum, Milwaukee, 154 pp.

- de Freitas MA, Pereira Fagundes de França D, Bernarde PS (2012) Squamata, Serpentes, Dipsadidae, Philodryas viridissima (Linnaeus, 1758): first record in the state of Acre, northern Brazil. Journal of species lists and distribution 8: 258–259. DOI: 10.15560/8.2.258

- Cunha OR, Nascimento FP (1993) Ofídios da Amazônia. As cobras da região leste do Pará. Papéis Avulsos Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi 40: 9–87.

- dos Santos-Costa MC, Maschio GF, da Costa Prudente AL (2015) Natural history of snakes from Floresta Nacional de Caxiuanã, eastern Amazonia, Brazil. Herpetology Notes 8: 69–98.

- Photo by Chris Lima.

- Jorge RF, Simões PI (2018) Philodryas viridissima (Common Green Racer): diet. Herpetological Review 49: 761–762.

- Chávez-Arribasplata JC, Almora CE, Pellón JJ, Venegas PJ (2016) Bat consumption by Philodryas viridissima (Serpentes: Colubridae) in the Amazon Basin of southeastern Peru. Phyllomedusa 15: 195–197.

- Marques OAV (1999) Defensive behavior of the green snake Philodryas viridissimus (Linnaeus) (Colubridae, Reptilia) from the Atlantic Forest in Northeastern Brazil. Revista Brasileira de Zoologia 16: 265–266. DOI: 10.1590/S0101-81751999000100023

- Campbell JA, Lamar WW (2004) The venomous reptiles of the western hemisphere. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, 774 pp.

- Means DB (2010) Ophidism by the Green Palmsnake. Wilderness and Environmental Medicine 21: 46–49. DOI: 10.1016/j.wem.2009.12.008

- Mota da Silva A, da Graça Mendes VK, Monteiro WM, Bernarde PS (2019) Non-venomous snakebites in the western Brazilian Amazon. Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical 52 2–5. DOI: 10.1590/0037-8682-0120-2019

- Gutiérrez-Cárdenas P, Caicedo J, Rivas G, Nogueira C, Cisneros-Heredia DF, Gonzales L (2019) Philodryas viridissima. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org. DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-3.RLTS.T15182284A15182298.en

- Nogueira CC, Argôlo AJS, Arzamendia V, Azevedo JA, Barbo FE, Bérnils RS, Bolochio BE, Borges-Martins M, Brasil-Godinho M, Braz H, Buononato MA, Cisneros-Heredia DF, Colli GR, Costa HC, Franco FL, Giraudo A, Gonzalez RC, Guedes T, Hoogmoed MS, Marques OAV, Montingelli GG, Passos P, Prudente ALC, Rivas GA, Sanchez PM, Serrano FC, Silva NJ, Strüssmann C, Vieira-Alencar JPS, Zaher H, Sawaya RJ, Martins M (2019) Atlas of Brazilian snakes: verified point-locality maps to mitigate the Wallacean shortfall in a megadiverse snake fauna. South American Journal of Herpetology 14: 1–274. DOI: 10.2994/SAJH-D-19-00120.1

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington D.C., 882 pp.

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Chlorosoma viridissimum in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Colombia | Caquetá | Tres esquinas | Cárdenas Hincapié & Lozano Bernal 2023 |

| Colombia | Caquetá | Vereda El Vergel | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Napo | Jatun Sacha Biological Reserve | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Napo | Limonconcha | UIMNH 61247; collection database |

| Ecuador | Napo | Wild Sumaco Wildlife Sanctuary | Camper et al. 2021 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Estación Científica Yasuni | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Anga Cocha | Ortega Andrade 2010 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Montalvo | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Palanda, east of Sarayacu | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Plataforma Mazaramo | Ortega Andrade 2010 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Pastaza | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Sarayacu | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Perú | Amazonas | Río Cenepa | MVZ 2260; VertNet |

| Perú | Loreto | Iquitos | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Perú | Loreto | Pampa hermosa | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Perú | Loreto | Pongo Chinim | Pitman et al. 2012 |

| Perú | Loreto | Río Marañon | Nogueira et al. 2019 |