Published October 10, 2019. Updated July 21, 2024. Open access. Peer-reviewed. | Purchase book ❯ |

Alcedo Giant-Tortoise (Chelonoidis vandenburghi)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Testudines | Testudinidae | Chelonoidis vandenburghi

English common names: Alcedo Giant-Tortoise.

Spanish common names: Galápago de Alcedo, tortuga gigante de Alcedo.

Recognition: ♂♂ 129 cmMaximum straight length of the carapace. ♀♀ 89.7 cmMaximum straight length of the carapace..1 Chelonoidis vandenburghi is the only species of giant tortoise known to naturally occur on and around Alcedo Volcano in central Isabela Island. The species is recognizable by its domed carapace shape (Fig. 1).1 The males of C. vandenburghi are larger than females and have a distinctively concave plastron.

Figure 1: Individuals of Chelonoidis vandenburghi from Zoológico de Quito () and Eco Zoológico San Martín (), genetically identified by Russello et al. 2007.

Natural history: Chelonoidis vandenburghi is a diurnal and terrestrial tortoise that inhabits the evergreen forests, seasonally dry forests, and humid grasslands of Alcedo Volcano. These tortoises spend most of their time feeding, resting on soil, or congregating in muddy rain pools.2 At night, they sleep out in the open.3 Their diet includes grasses, shrubs, sedges, forbs, leaves of trees, lichens, and fruits, including those from the strongly irritant manzanillo.2,4,5 The tortoises obtain water from their diet or from rain pools.2 The males of C. vandenburghi fight each other using a combination of biting, gaping, pushing, and neck extensions.6 When mating, they produce resounding guttural sounds.7 The females begin nesting between May and June at the end of the rainy season, and they lay 6–26 eggs in areas of soft soil.2 Not all of these hatch; some nests are destroyed by fungal infections during periods of high rainfall.8 Previously, before 2004, nests were lost due to trampling by feral donkeys.9 The hatchlings of C. vandenburghi stay in warmer, lower elevation areas for their first 10–15 years.3 As adults, they are seasonal migrants, traveling up to 13 km in a matter of days.10 Some individuals routinely move over a distance of >25 km in a semi-circular path along the rim of Alcedo Volcano’s caldera, and descend to the floor of the caldera or to the volcano’s slopes to exploit new vegetation after the rains.11,12 There are records of tortoises of this species dying by falling from cliffs or by drowning during floods.8

Conservation: Vulnerable Considered to be facing a high risk of extinction in the mid-term future..13 Chelonoidis vandenburghi is listed in this category because nearly 83% of the population disappeared in the last 180 years.13 Before human impact, there were approximately 38,000 tortoises on Alcedo.13 Now, about 6,320 individuals remain and these numbers are increasing following the eradication of exotic species (goats, pigs, and donkeys), which formerly either preyed on the eggs and the hatchlings, trampled nests, or destroyed tortoise habitat.13–15 Unlike other Galápagos tortoises, C. vandenburghi was probably never heavily exploited by whalers due to the inaccessibility of Alcedo Volcano; however, volcanic activity has produced major reductions of the C. vandenburghi population in recent times.16 The last major eruption of Alcedo was about 100,000 years ago17 and it is the most likely explanation for the low genetic diversity of the species.16

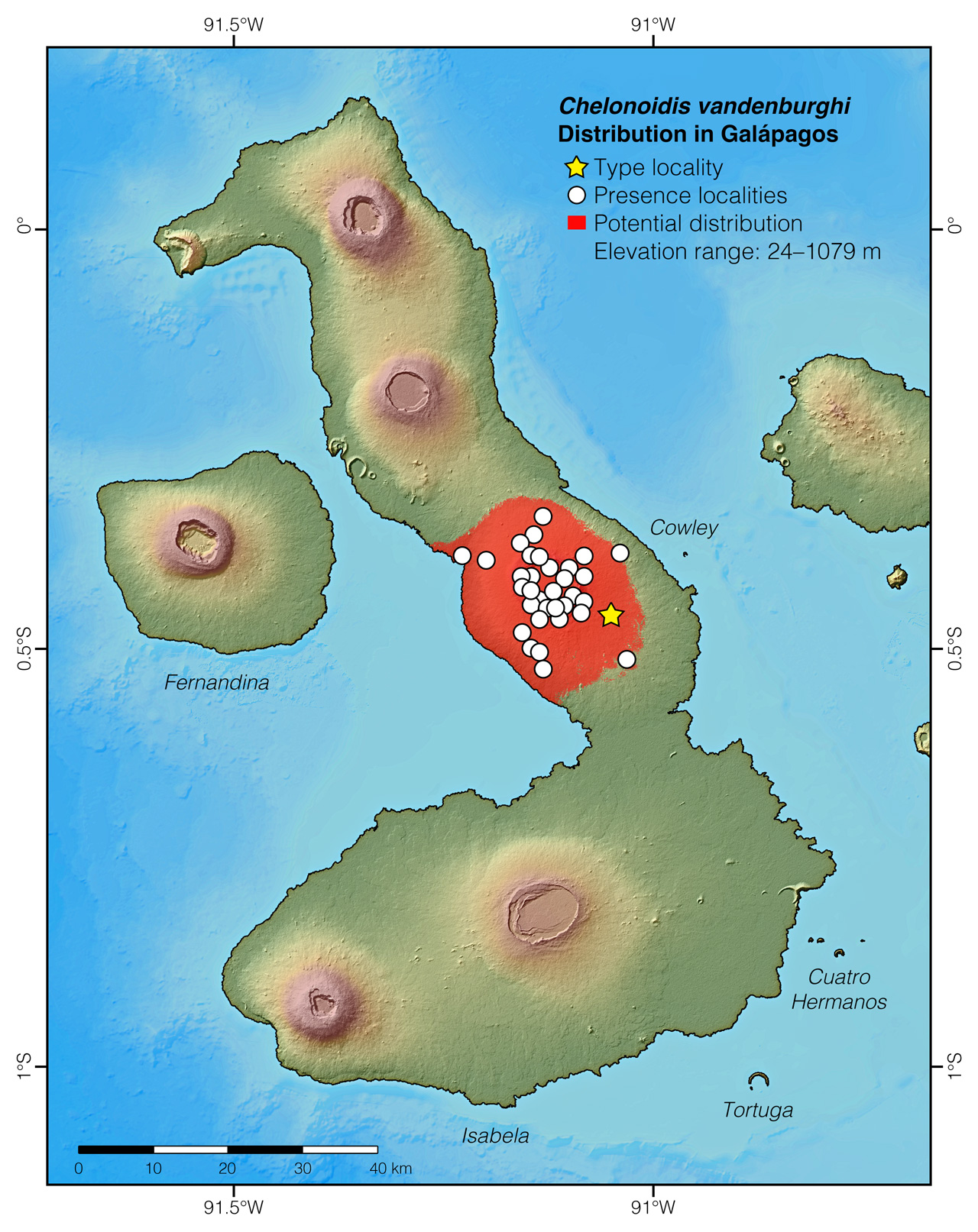

Distribution: Chelonoidis vandenburghi is endemic to an area of approximately 476 km2 on Alcedo Volcano in central Isabela Island, Galápagos, Ecuador (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Distribution of Chelonoidis vandenburghi in Galápagos. The star corresponds to the type locality: Cowley Mountain. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The name Chelonoidis comes from the Greek word chelone (=tortoise).18 The specific epithet vandenburghi honors John Van Denburgh (1872–1924),7 curator of herpetology at the California Academy of Sciences, in recognition of his invaluable work on Galápagos tortoises.

See it in the wild: Alcedo Giant-Tortoises can be seen with almost complete certainty at Urbina Bay, a coastal tourism site near the northwestern base of Alcedo Volcano on Isabela Island. However, the best place to see and photograph individuals of Chelonoidis vandenburghi is in and around the caldera of Alcedo Volcano, which seasonally holds hundreds or even thousands of giant tortoises.

Special thanks to Ellen Smith for symbolically adopting the Alcedo Giant-Tortoise and helping bring the Reptiles of Ecuador book project to life.

Click here to adopt a species.

Authors: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador. and Juan M GuayasaminbAffiliation: Universidad San Francisco de Quito, Quito, Ecuador.

Academic reviewers: Adalgisa CacconecAffiliation: Yale University, New Haven, United States.

Photographers: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador. and Jose VieiradAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,eAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Arteaga A, Guayasamin JM (2024) Alcedo Giant-Tortoise (Chelonoidis vandenburghi). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/ITLQ5963

Literature cited:

- Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J, Tapia W, Guayasamin JM (2019) Reptiles of the Galápagos: life on the Enchanted Islands. Tropical Herping, Quito, 208 pp. DOI: 10.47051/AQJU7348

- Fowler LE (1983) The population and feeding ecology of tortoises and feral burros on Volcán Alcedo, Galápagos Islands. PhD Thesis, University of Florida, 150 pp.

- Swingland IR (1989) Geochelone elephantopus. Galápagos giant tortoises. In: Swingland IR, Klemens MW (Eds) The conservation biology of tortoises. Occasional Papers of the IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC), Gland, 24–28.

- Slevin JR (1935) An account of the reptiles inhabiting the Galápagos Islands. Bulletin of the New York Zoological Society 38: 3–24.

- Fritts TH, Fritts PR (1982) Race with extinction: herpetological notes of J. R. Slevin’s journey to the Galápagos 1905–1906. Herpetological Monographs 1: 1–98. DOI: 10.2307/1466971

- Schafer SF, Krekorian CO (1983) Agonistic behavior of the Galápagos tortoise, Geochelone elephantopus, with emphasis on its relationship to saddle-backed shell shape. Herpetologica 39: 448–456.

- DeSola CR (1930) The Liebespiel of Testudo vandenburghi, a new name for the mid-Albemarle Island Galápagos tortoise. Copeia 1930: 79–80.

- Márquez C, Wiedenfeld DA, Naranjo S, and Llerena W (2008) The 1997-8 El Niño and the Galápagos tortoises Geochelone vandenburghi on Alcedo Volcano, Galápagos. Galápagos Research 65: 7–10.

- Fowler de Neira LE, Roe JH (1984) Emergence success of tortoise nests and the effect of feral burros on nest success on Volcán Alcedo, Galápagos. Copeia 1984: 702–707. DOI: 10.2307/1445152

- Bastille‐Rousseau G, Yackulic CB, Frair JL, Cabrera F, Blake S (2016) Allometric and temporal scaling of movement characteristics in Galápagos tortoises. Journal of Animal Ecology 85: 1171–1181. DOI: 10.1111/1365-2656.12561

- Bastille-Rousseau G, Gibbs JP, Yackulic CB, Frair JL, Cabrera F, Rousseau LP, Wikelski M, Kümmeth F, Blake S (2017) Animal movement in the absence of predation: environmental drivers of movement strategies in a partial migration system. Oikos 126: 1004–1019. DOI: 10.1111/oik.03928

- Pritchard PCH (1996) The Galápagos tortoises. Nomenclatural and survival status. Chelonian Research Monographs 1: 1–85.

- Cayot LJ, Gibbs JP, Tapia W, Caccone A (2018) Chelonoidis vandenburghi. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org. DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T9027A144766471.en

- Márquez C, Wiedenfeld D, Snell H, Fritts T, MacFarland C, Tapia W, Naranjo S (2004) Estado actual de las poblaciones de tortugas terrestres gigantes (Geochelone spp., Chelonia: Testudinidae) en las islas Galápagos. Ecología Aplicada 3: 98–111.

- Márquez C, Gibbs JP, Carrión V, Naranjo S, Llerena A (2012) Population response of giant Galápagos tortoises to feral goat removal. Restoration Ecology 21: 181–185. DOI: 10.1111/j.1526-100X.2012.00891.x

- Beheregaray LB, Ciofi C, Geist D, Gibbs JP, Caccone A, Powell JR (2003) Genes record a prehistoric volcano eruption in the Galápagos. Science 302: 75. DOI: 10.1126/science.1087486

- Geist D, Howard KA, Jellinek AM, Rayder S (1994) The volcanic history of Volcán Alcedo, Galápagos Archipelago: a case study of rhyolitic oceanic vulcanism. Bulletin of Vulcanology 56: 243–260. DOI: 10.1007/BF00302078

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington, 882 pp.

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Chelonoidis vandenburghi in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used. Asterisk (*) indicates type locality.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Alcedo, eastern rim | Bastille‐Rousseau et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Alcedo, northeastern rim | Bastille‐Rousseau et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Alcedo, northern rim | Bastille‐Rousseau et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Alcedo, northern slope | Bastille‐Rousseau et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Alcedo, northwestern rim | Bastille‐Rousseau et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Alcedo, southeastern rim | Bastille‐Rousseau et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Alcedo, southeastern slope | Bastille‐Rousseau et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Alcedo, southern rim | Bastille‐Rousseau et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Alcedo, southwestern rim | Bastille‐Rousseau et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Alcedo, southwestern slope | Bastille‐Rousseau et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Alcedo, western rim | Bastille‐Rousseau et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Area 2 | Fowler 1983 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Caldera of Alcedo, eastern part | Bastille‐Rousseau et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Caldera of Alcedo, northern part | Fowler de Neira and Roe 1984 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Caldera of Alcedo, northwestern part | Bastille‐Rousseau et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Caldera of Alcedo, SC part | Bastille‐Rousseau et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Caldera of Alcedo, southeastern part | Bastille‐Rousseau et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Caldera of Alcedo, southern part | Bastille‐Rousseau et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Caldera of Alcedo, SSE part | Bastille‐Rousseau et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Caldera of Alcedo, SSW part | Bastille‐Rousseau et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Cowley Mountain* | Van Denburgh 1907 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Eastern belt of Alcedo at 400 feet | Fritts and Fritts 1982 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Elizabeth Bay, 10 km NW of | Bastille‐Rousseau et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Elizabeth Bay, 13 km NW of | Bastille‐Rousseau et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Elizabeth Bay, 14 km NW of | Bastille‐Rousseau et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Fumarole | Fowler de Neira and Roe 1984 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Midcamp | Fowler 1983 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Northern rim of Alcedo, 5 km N of | Snow 1964 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Perry isthmus, 10 km NW of | Townsend 1925 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Plateau of Alcedo, northern part | Fowler 1983 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Urbina Bay | This work |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Urbina Bay, 3 km E of | Márquez et al 2004 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Urbina Bay, 8 km NE of | Bastille‐Rousseau et al. 2016 |