Floreana Giant-Tortoise |

Reptiles of Ecuador | Testudines | Testudinidae | Chelonoidis niger

English common names: Floreana Giant-Tortoise, Charles Island Giant-Tortoise.

Spanish common names: Galápago de Floreana, tortuga gigante de Floreana.

Recognition: ♂♂ 137.6 cm ♀♀ 88 cm. Chelonoidis niger was the only species of giant tortoise known to occur on Floreana Island. It was recognizable by its strongly saddlebacked carapace.

Picture: Adult male. Centro de Crianza Fausto Llerena. Galápagos, Ecuador. | |

| |

Picture: Adult female. Centro de Crianza Fausto Llerena. Galápagos, Ecuador. | |

| |

Picture: Adult female. Centro de Crianza Fausto Llerena. Galápagos, Ecuador. | |

| |

Picture: Adult female. Centro de Crianza Fausto Llerena. Galápagos, Ecuador. | |

| |

Picture: Juvenile. Centro de Crianza Fausto Llerena. Galápagos, Ecuador. | |

| |

Picture: Juvenile. Centro de Crianza Fausto Llerena. Galápagos, Ecuador. | |

| |

Natural history: Historically extremely common. Chelonoidis niger was a diurnal and terrestrial tortoise inhabiting deciduous forests and evergreen forests. Floreana Giant-Tortoises fed on cacti, bitterbush, and grasses,1,2 and obtained water from crevices in the lava rocks or from springs.1 During the rainy season, adults of C. niger descended to the grass covered lowlands to feed.1 Hatchlings were preyed upon by owls.3

Conservation: Extinct.4 The extinction of Chelonoidis niger, which had an estimated population of 8,000 individuals, is thought to have occurred in the 1840s or 1850s.1,5,6 The causes of extinction include extensive overexploitation for food by sailors (mostly whalers, who alone killed at least 1,775 tortoises between 1831 and 1837) and settlers (Floreana was the first island in Galápagos to be colonized),7,8 and the introduction of exotic species (including goats, pigs, dogs, cats, donkeys, and rodents),4 which either prey on the eggs and the hatchlings, or destroy tortoise habitat.

"At 4:00 am of the 28th of October, we accompanied Mr. Cole and ten men, in the pinnace, to the black beach, about three miles distant, to procure terrapin: we arrive there at daylight, and proceeded to the spring, about two miles from the landing. We found a great many terrapin there. They were generally too large for a man to carry, and it was only by culling them that one could be obtained to convey down the shore."

Charles Barnard, captain of the merchant vessel Millwood, 1816.7

Although this species is officially extinct, several hybrids between the Floreana Giant-tortoise and the Wolf Volcano Giant-Tortoise (Chelonoidis becki) have been recently discovered around Wolf Volcano on northern Isabela Island, probably as a result of C. niger being released on Isabela by pirates and whalers during the early 19th century.9–11 These hybrids, through targeted captive breeding, have the potential to actually "resuscitate" the extinct Floreana Giant-tortoise! This is now a real possibility thanks to a combination of genetic and field research efforts.11,12 The breeding program to bring back the Floreana Giant-Tortoise has already produced 67 tortoises that hatched in captivity in 2018.

"The terrapin we had taken were stowed in different parts of the ship, some among the casks between the decks, some on deck; it mattered little to us, and apparently less to them, what their accommodations were, so long as they kept out from under foot. With the food they afforded and that of the blackfish constantly on hand, we fared quite sumptuosly. Our cook used to parboil a sufficient quantity of terrapin over night for next morning's breakfast, when not obliged to be in the boats."

Jethro Daggett, captain of the whaling ship Apollo, 1816.7

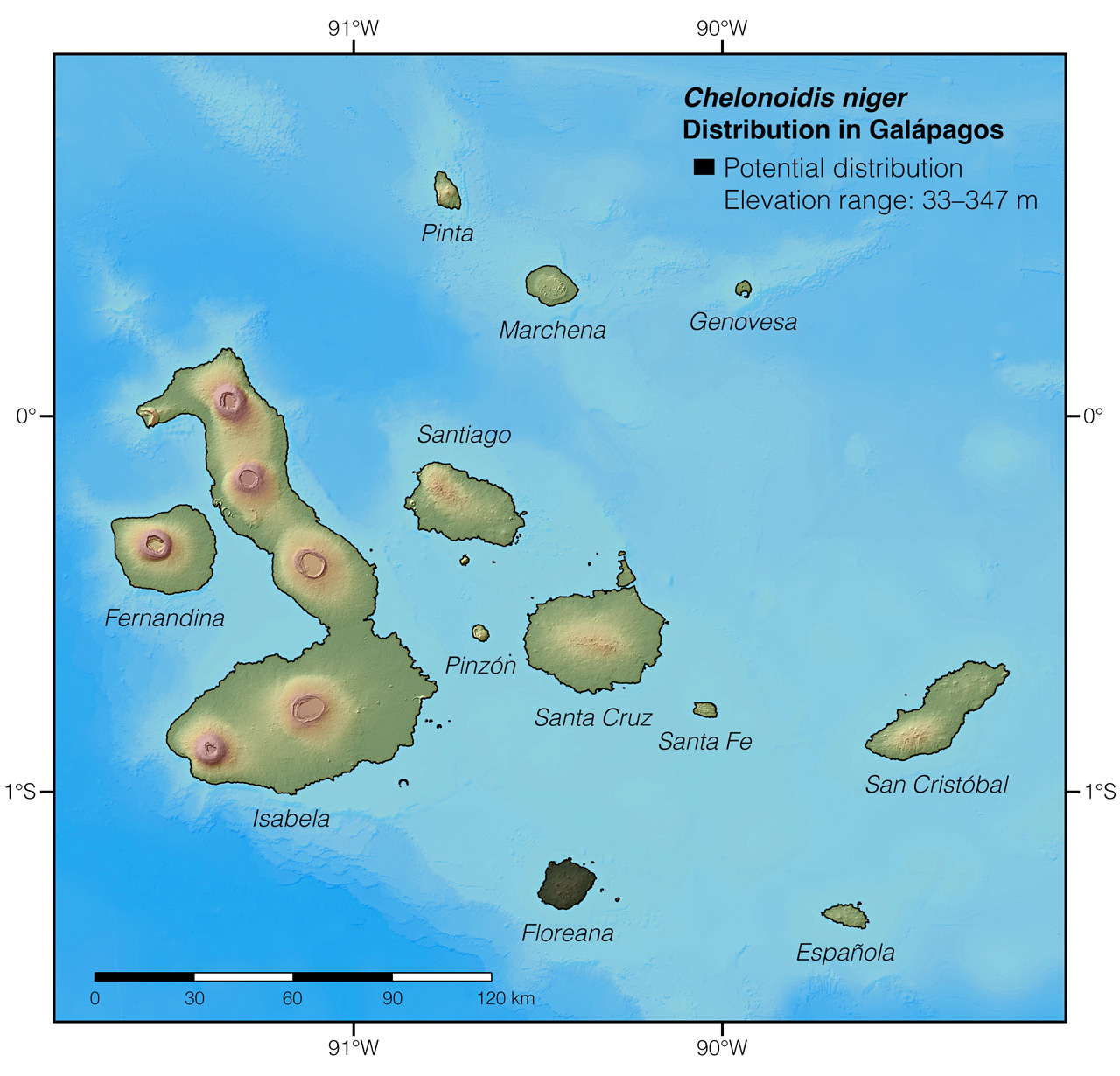

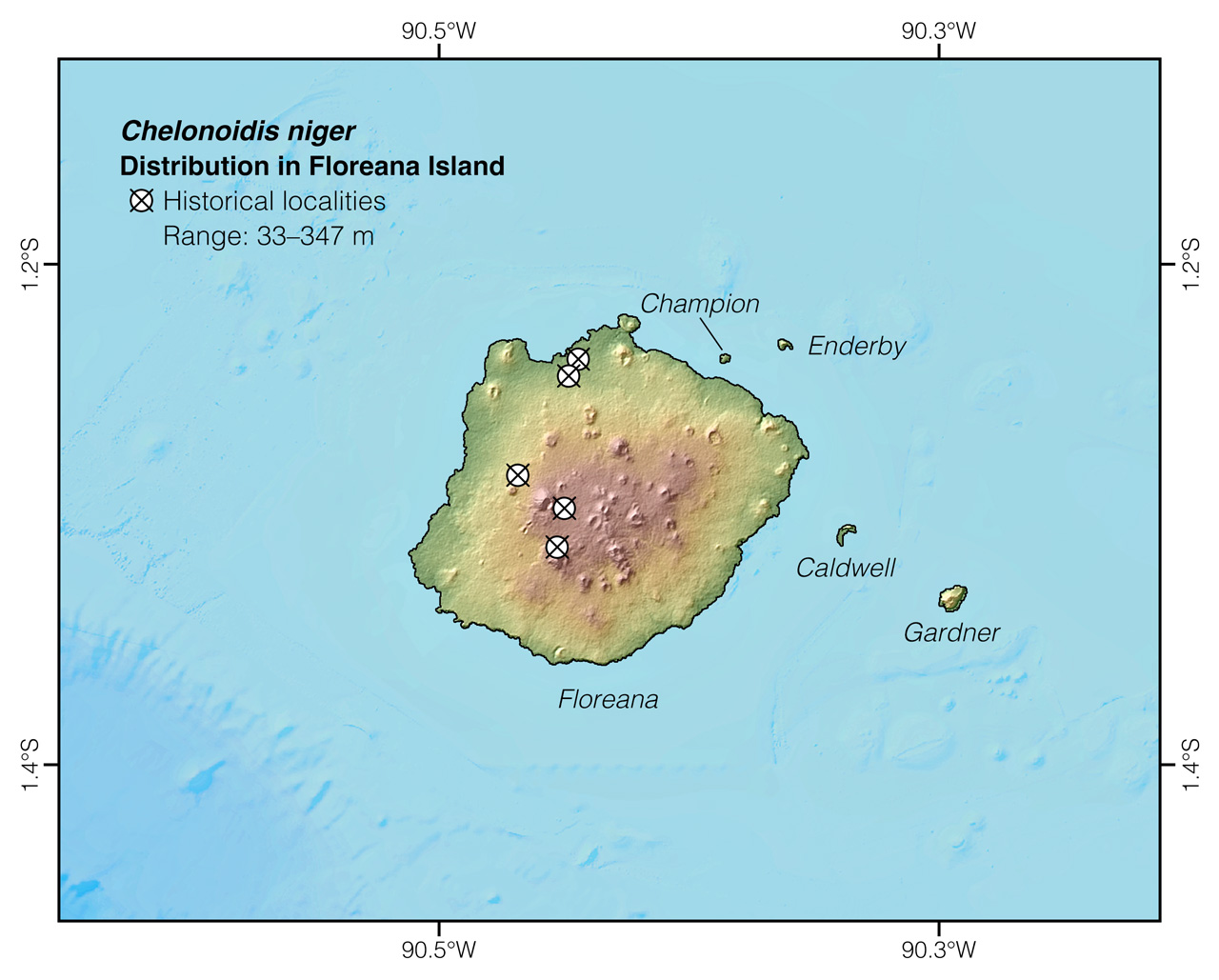

Distribution: Chelonoidis niger was historically endemic to Floreana, an island having an area of 173 km2 and a maximum elevation of 640 m. Galápagos, Ecuador.

Etymology: The generic name Chelonoidis comes from the Greek word chelone (meaning “tortoise”).13 The specific epithet niger is a Latin word meaning “black”, and is probably a reference to the blackish color of the juvenile on which the original description was based.

See it in the wild: There are, presumably, no wild purebred tortoises of this species, but individuals with up to 80% Chelonoidis niger ancestry can be seen at the Centro de Crianza Fausto Llerena on Santa Cruz Island.

Special thanks to Adriana Coll De Peña for symbolically adopting the Floreana Giant-Tortoise and helping bring the Reptiles of Ecuador book project to life.

Click here to adopt a species.

Authors: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador. and Juan M GuayasaminbAffiliation: Laboratorio de Biología Evolutiva, Universidad San Francisco de Quito (USFQ), Quito, Ecuador.,cAffiliation: Galapagos Science Center, Galápagos, Ecuador.,dAffiliation: Centro de Investigación de la Biodiversidad y Cambio Climático, Universidad Tecnológica Indoamérica, Quito, Ecuador.

Academic reviewers: Adalgisa Caccone.

Photographers: Jose VieiraaAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,eAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador. and Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Arteaga A, Guayasamin JM (2020) Chelonoidis niger. In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com

Literature cited:

- Broom R (1929) On the extinct Galápagos tortoise that inhabited Charles Island. Zoologica 9: 313–320.

- Snow DW (1964) The giant tortoises of the Galápagos Islands: their present status and future chances. Oryx 7: 277–290.

- Steadman DW (1986) Holocene vertebrate fossils from Isla Floreana, Galápagos. Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology 413: 1–103.

- van Dijk PP, Rhodin AGJ, Cayot LJ, Caccone A (2017) Chelonoidis niger. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org

- Pritchard PCH (1996) The Galápagos tortoises. Nomenclatural and survival status. Chelonian Research Monographs 1: 1–85.

- Heller E (1903) Papers from the Hopkins-Stanford Galápagos Expedition, 1898-1899. XIV. Reptiles. Proceedings of the Washington Academy of Sciences 5:39–98.

- Townsend CH (1925) The Galápagos tortoises in their relation to the whaling industry: a study of old logbooks. Zoologica 4: 55–135.

- Baur G (1889) The gigantic land tortoises of the Galápagos Islands. The American Naturalist 23: 1039–1057.

- Garrick RC, Benavides E, Russello MA, Gibbs JP, Poulakakis N, Dion KB, Hyseni C, Kajd B (2012) Genetic rediscovery of an 'extinct' Galápagos giant tortoise species. Current Biology 22: 10–11.

- Poulakakis N, Glaberman S, Russello M, Beheregaray LB, Ciofi C, Powell JR, Caccone A (2008) Historical DNA analysis reveals living descendants of an extinct species of Galápagos tortoise. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 105: 15464–15469.

- Russello MA, Poulakakis N, Gibbs JP, Tapia W, Benavides E, Powell JR, Caccone A (2010) DNA from the past informs ex situ conservation for the future: An "Extinct" species of Galápagos tortoise identified in captivity. PLoS ONE 5: e8683.

- Miller JM, Quinzin MC, Poulakakis N, Gibbs JP, Beheregaray LB, Garrick RC, Russello MA, Ciofi C, Edwards DL, Hunter EA, Tapia W, Rueda D, Carrión J, Valdivieso AA, Caccone A (2017) Identification of genetically important individuals of the rediscovered Floreana Galápagos giant tortoise (Chelonoidis elephantopus) provide founders for species restoration program. Scientific Reports 7: 11471.

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington, 882 pp.