Sierra Negra Giant-Tortoise |

Reptiles of Ecuador | Testudines | Testudinidae | Chelonoidis guntheri

English common names: Sierra Negra Giant-Tortoise, Günther's Giant-Tortoise.

Spanish common names: Galápago de Sierra Negra, tortuga gigante de Sierra Negra.

Recognition: ♂♂ 120.5 cm ♀♀ 92.3 cm. Chelonoidis guntheri is generally the only species of giant tortoise known to naturally occur around Sierra Negra Volcano on Isabela Island. Adults of C. guntheri may have one of two distinct carapace forms: domed or flattened (known as "aplastadas"). No other giant tortoise species occurring on Isabela Island has a flattened carapace. However, tortoises with the domed carapace form as well as hatchlings and juveniles having either carapace form may be indistinguishable (without the use of genetic information) from the Cerro Azul Giant-Tortoise (C. vicina), a closely related species that may be found living alongside with C. guntheri in some localities.

Picture: Adult male. Centro de Crianza Arnaldo Tupiza. Galápagos, Ecuador. | |

| |

Picture: Adult male. Centro de Crianza Arnaldo Tupiza. Galápagos, Ecuador. | |

| |

Picture: Adult female. Centro de Crianza Arnaldo Tupiza. Galápagos, Ecuador. | |

| |

Picture: Adult female. Centro de Crianza Arnaldo Tupiza. Galápagos, Ecuador. | |

| |

Picture: Adult female. Centro de Crianza Arnaldo Tupiza. Galápagos, Ecuador. | |

| |

Picture: Juvenile. Centro de Crianza Arnaldo Tupiza. Galápagos, Ecuador. | |

| |

Picture: Juvenile. Centro de Crianza Arnaldo Tupiza. Galápagos, Ecuador. | |

| |

Picture: Hatchling. Centro de Crianza Arnaldo Tupiza. Galápagos, Ecuador. | |

| |

Natural history: Common. Chelonoidis guntheri is a diurnal and terrestrial tortoise that inhabits deciduous forests, evergreen forests, dry grasslands, agricultural land, and areas of introduced vegetation. Sierra Negra Giant-Tortoises feed on herbs, grass, cacti, lichen, and fruits, including those from the strongly irritant manzanillo.1–4 Tortoises with a domed carapace graze mostly on low-growing herbaceous vegetation, while those with flattened shells usually feed on shrubs. Males fight with each other using a combination of biting, gaping, neck extensions, and shell-bumping.5 When mating, the tortoises produce resounding guttural sounds. Females of C. guntheri lay 6–17 (but usually 6–11) eggs.6,7 Juveniles of C. guntheri stay in warmer lowland areas during their first 10–15 years of life.8 As adults, they move across their elevation range.8

Conservation: Critically Endangered.9 Chelonoidis guntheri is listed in this category because it is estimated that ~99% of the population disappeared in the last 180 years.9 The number of Sierra Negra Giant-Tortoises declined catastrophically from about 71,000 individuals before human contact to 300–500 in the early 1970s.9,10 Historical causes of the population decline include extensive overexploitation for food and oil by sailors (mostly whalers) and settlers and the introduction of exotic species (including goats, pigs, dogs, rodents, and fire ants), which either prey on tortoise eggs and hatchlings or destroy their habitat.9,11 In southern Isabela Island, the establishment of a penal colony (from 1944 to 1959), a military presence during World War II, and the foundation of the coastal village of Puerto Villamil in 1895 resulted in Sierra Negra Giant-Tortoises being harvested to the brink of extinction.9,12

To this day, the recovery of Chelonoidis guntheri remains restrained. Pigs and fire ants still decimate nests, feral cattle compete with the tortoises for resources, and the illegal slaughter and poaching of tortoises still occurs.9,13 Another threat faced by C. guntheri is volcanic eruptions, which, in addition to directly causing mortality, destroy and fragment tortoise habitat.9 Today, the population of the Sierra Negra Giant-Tortoise includes about 400–700 mature individuals,9,14 but whether these numbers are increasing is unknown. Some of the positive conservation actions carried out by the Galápagos National Park include the eradication of goats9 and the establishment of a head-starting program at the Centro de Crianza Arnaldo Tupiza, in which young tortoises are raised in captivity and subsequently released into the wild.

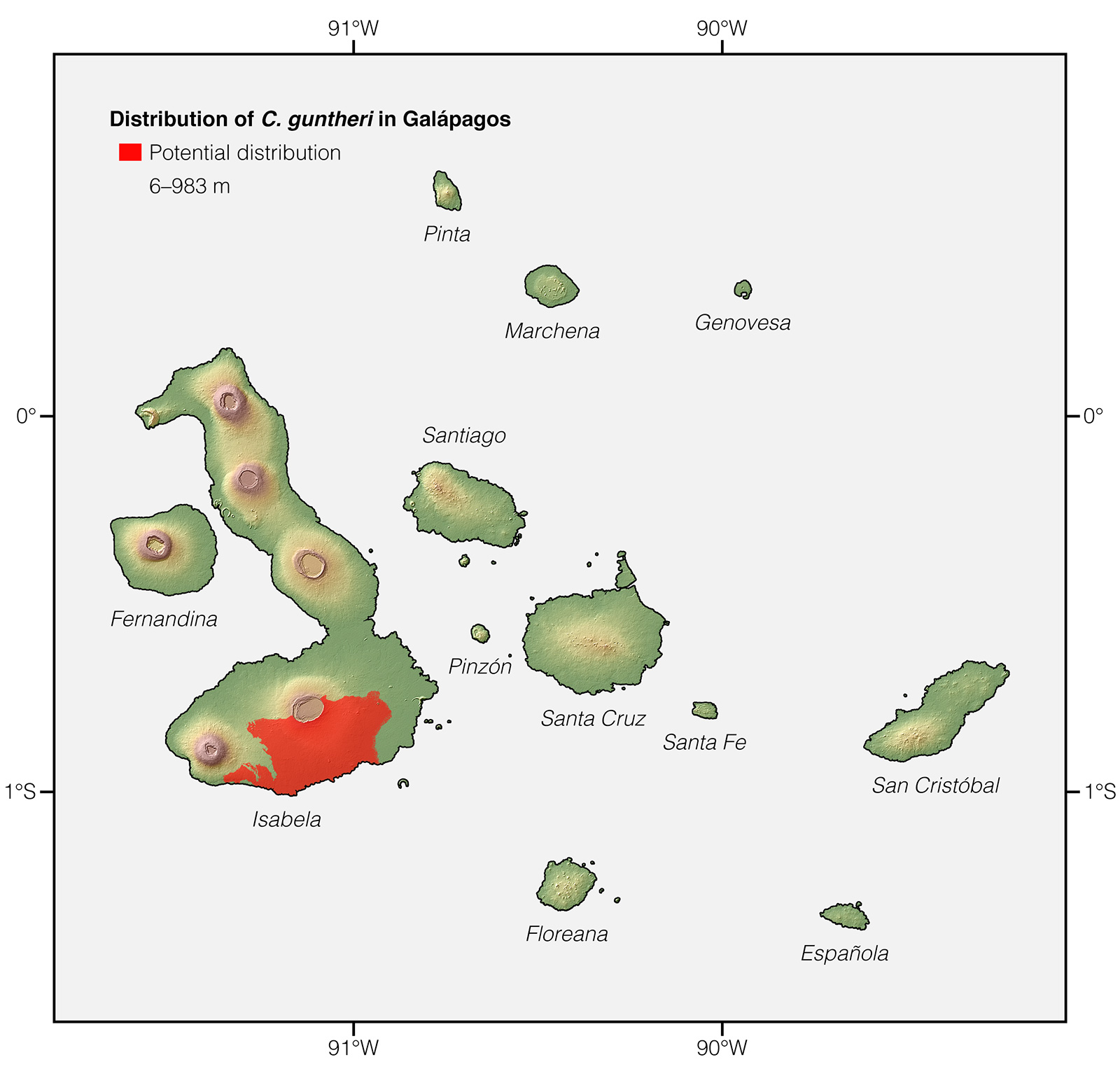

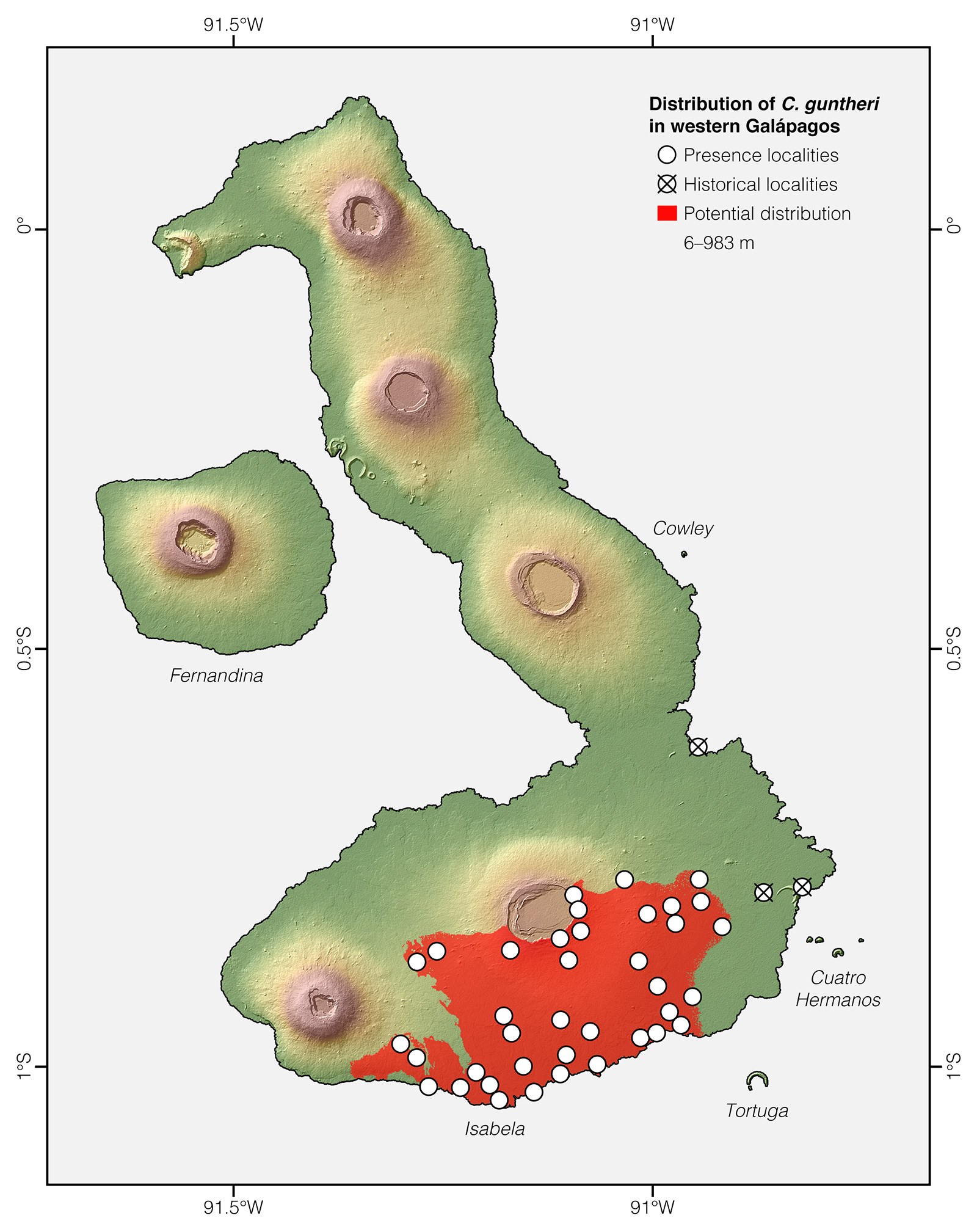

Distribution: Chelonoidis guntheri is endemic to an estimated 817 km2 area on the Sierra Negra Volcano and surrounding areas in the southern part of Isabela Island. Galápagos, Ecuador.

Etymology: The generic name Chelonoidis comes from the Greek word chelone (meaning “tortoise”).15 The specific epithet guntheri honors Albert Günther (1830–1914), a German-born British zoologist, ichthyologist, and herpetologist, best known for his role as Keeper of Zoology at the Natural History Museum in London.

See it in the wild: Individuals of Chelonoidis guntheri can be seen year-round with ~80–90% certainty at some tourism sites near Puerto Villamil, including the trail to Muro de las Lágrimas and along the crater of Sierra Negra Volcano. Head-started juveniles of C. guntheri can be seen at the Centro de Crianza Arnaldo Tupiza in Isabela Island.

Special thanks to Michael Lavery for symbolically adopting the Sierra Negra Giant-Tortoise and helping bring the Reptiles of Ecuador book project to life.

Click here to adopt a species.

Authors: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador. and Juan M GuayasaminbAffiliation: Laboratorio de Biología Evolutiva, Universidad San Francisco de Quito (USFQ), Quito, Ecuador.,cAffiliation: Galapagos Science Center, Galápagos, Ecuador.,dAffiliation: Centro de Investigación de la Biodiversidad y Cambio Climático, Universidad Tecnológica Indoamérica, Quito, Ecuador.

Academic reviewers: Adalgisa Caccone.

Photographers: Jose VieiraaAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,eAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Arteaga A, Guayasamin JM (2020) Chelonoidis guntheri. In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com

Literature cited:

- Slevin JR (1935) An account of the reptiles inhabiting the Galápagos Islands. Bulletin of the New York Zoological Society 38: 3–24.

- Fritts TH, Fritts PR (1982) Race with extinction: herpetological notes of J. R. Slevin's journey to the Galápagos 1905–1906. Herpetological Monographs 1: 1–98.

- Stewart A (1911) A botanical survey of the Galápagos Islands. Proceedings of the California Academy of sciences 1: 7–288.

- Darwin CR (1845) Journal of researches into the natural history and geology of the countries visited during the voyage of H.M.S. Beagle round the world, under the command of Capt. Fitz-Roy, R.N. John Murray, London, 519 pp.

- Schafer SF, Krekorian CO (1983) Agonistic behavior of the Galápagos tortoise, Geochelone elephantopus, with emphasis on its relationship to saddle-backed shell shape. Herpetologica 39: 448–456.

- Beck RH (1902) Field notes on the tortoises of the Galápagos Islands. Novitates Zoologicae 9: 375–380.

- Washington Tapia, unpublished data.

- Swingland IR (1989) Geochelone elephantopus. Galápagos giant tortoises. In: Swingland IR, Klemens MW (Eds) The conservation biology of tortoises. Occasional Papers of the IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC), Gland, 24–28.

- Cayot LJ, Gibbs JP, Tapia W, Caccone A (2018) Chelonoidis guntheri. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org

- MacFarland CG, Villa J, Toro B (1974) The Galápagos giant tortoises (Geochelone elephantopus). Part I: Status of the surviving populations. Biological Conservation 6: 118–133.

- Townsend CH (1925) The Galápagos tortoises in their relation to the whaling industry: a study of old logbooks. Zoologica 4: 55–135.

- Pritchard PCH (1996) The Galápagos tortoises. Nomenclatural and survival status. Chelonian Research Monographs 1: 1–85.

- Cayot LJ, Lewis E (1994) Recent increase in killing of giant tortoises on Isabela Island. Noticias de Galápagos 54: 2–7.

- Márquez C, Wiedenfeld D, Snell H, Fritts T, MacFarland C, Tapia W, Naranjo S (2004) Estado actual de las poblaciones de tortugas terrestres gigantes (Geochelone spp., Chelonia: Testudinidae) en las islas Galápagos. Ecología Aplicada 3: 98–111.

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington, 882 pp.