Pinzón Giant-Tortoise |

Reptiles of Ecuador | Testudines | Testudinidae | Chelonoidis duncanensis

English common names: Pinzón Giant-Tortoise, Duncan Island Giant-Tortoise.

Spanish common names: Galápago de Pinzón, tortuga gigante de Pinzón.

Recognition: ♂♂ 85.5 cm ♀♀ 79.5 cm. Chelonoidis duncanensis is the only species of giant tortoise known to naturally occur on Pinzón Island. It is recognizable by its saddlebacked carapace.

Picture: Adult male. Pinzón Island. Galápagos, Ecuador. | |

| |

Picture: Adult male. Pinzón Island. Galápagos, Ecuador. | |

| |

Picture: Adult female. Pinzón Island. Galápagos, Ecuador. | |

| |

Picture: Adult female. American Museum of Natural History. New York, United States. | |

| |

Picture: Juvenile. Pinzón Island. Galápagos, Ecuador. | |

| |

Picture: Juvenile. Centro de Crianza Fausto Llerena. Galápagos, Ecuador. | |

| |

Picture: Juvenile. Centro de Crianza Fausto Llerena. Galápagos, Ecuador. | |

| |

Natural history: Common. Chelonoidis duncanensis is a diurnal and terrestrial tortoise that inhabits deciduous and evergreen forests. Pinzón Giant-Tortoises are active early in the morning and late in the afternoon.1 During hot midday hours, they move into the shade and wallow in damp soil.1 After heavy rains, they also wallow in the mud.1 The tortoises obtain water from temporary ponds2 and from their diet, which includes cacti, shrubs, herbs, forbs, epiphytes, grass, moss, lichens, leaf-litter, and fungi.2–5 Adults of the Pinzón Giant-Tortoise make seasonal vertical migrations along established trails.2 Right after the rainy season, they descend into the grass-covered lowlands to feed.2 Here, the females deposit 2–8 eggs6 in soft soil.2 These hatch after 85–240 days.7,8 Hatchlings are preyed upon by hawks.9

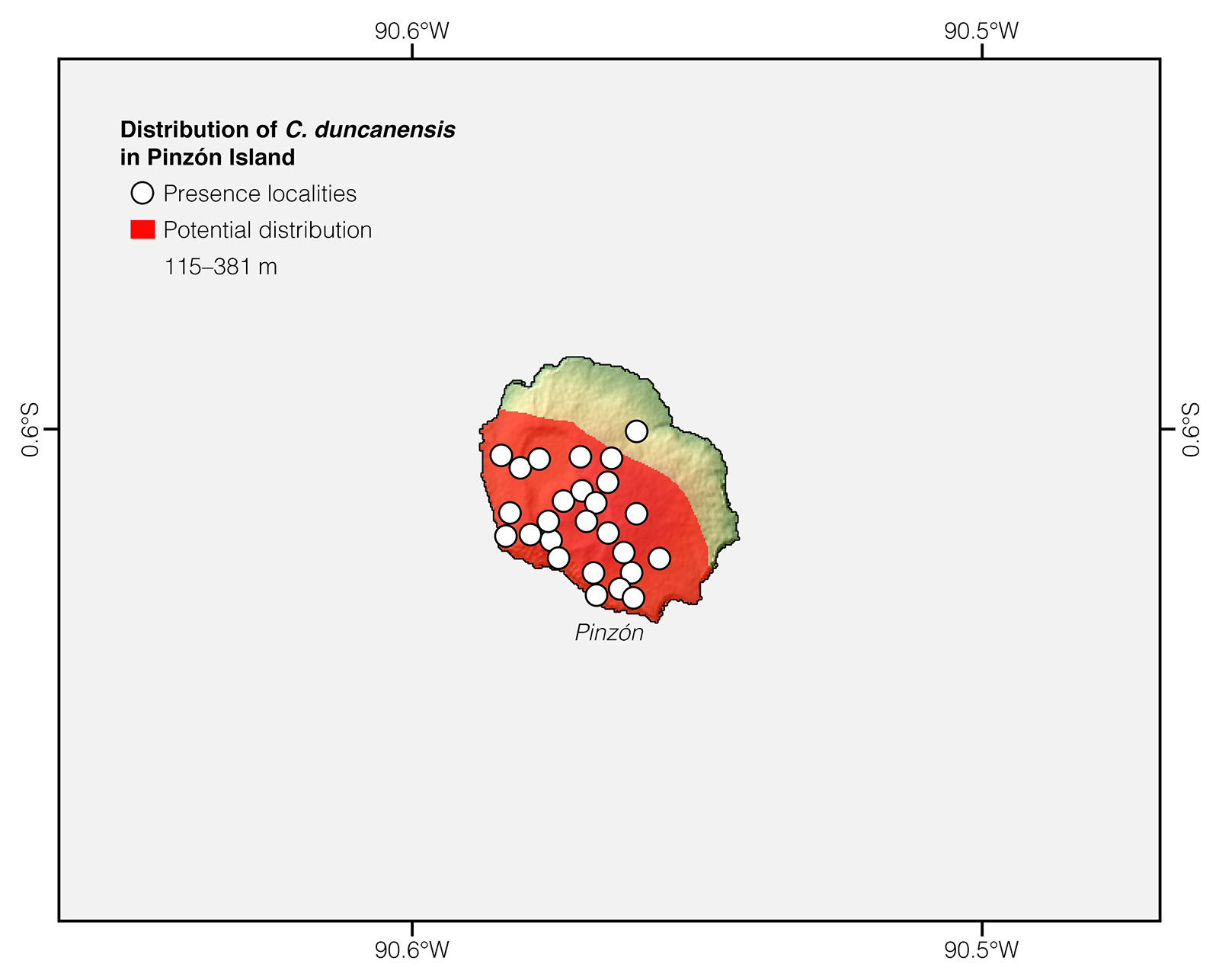

Conservation: Vulnerable.10 The population of Chelonoidis duncanensis declined catastrophically from about 850 individuals before human contact to ~100–200 in the early 1960s (representing a 78–89% decline).10 The bulk of the decline occurred between 1788 and 1868 during the whaling decades in the Pacific.11,12 The population decline was caused by extensive overexploitation for food by sailors (mostly whalers),10,11 scientific collecting to produce museum specimens (86 tortoises were taken by the California Academy of Sciences expedition in 1905–1906),13 and the introduction of black rats, which killed almost all tortoise hatchlings.14 Today, there are about 800 Pinzón Giant-Tortoises,8 and these numbers continue to grow thanks to the eradication of black rats from Pinzón Island in 2012 and to the head-starting program of the Galápagos National Park,10 in which young tortoises are raised in captivity and subsequently released into the wild. However, the Pinzón Giant-Tortoise is still listed as Vulnerable10 because its area of occupancy is no greater than 20 km2.

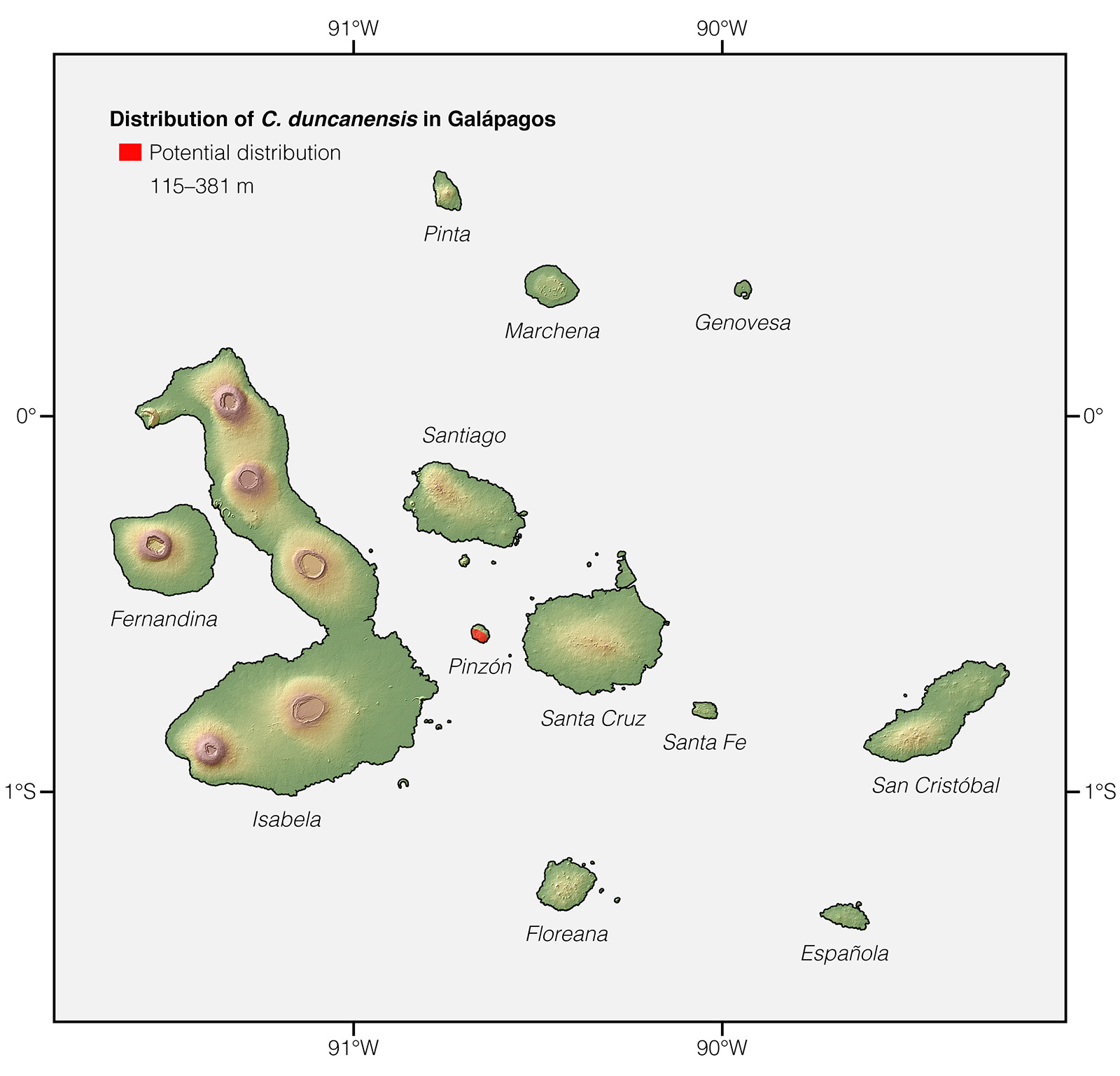

Distribution: Endemic to an estimated 12 km2 area in the highlands of Pinzón Island. Galápagos, Ecuador.

Etymology: The generic name Chelonoidis comes from the Greek word chelone (meaning “tortoise”).15 The specific epithet duncanensis refers to Pinzón, previously known as Duncan Island. The island was originally named after British admiral Adam Duncan.

See it in the wild: Chelonoidis duncanensis occurs on Pinzón Island, which is inaccessible to tourism. Researchers and members of the Galápagos National Park may visit the habitat of C. duncanensis, but only in the context of a scientific expedition or a conservation agenda. Head-started juveniles of C. duncanensis can be seen at the Centro de Crianza Fausto Llerena in Santa Cruz Island.

Special thanks to Vanessa Rischitelli for symbolically adopting the Pinzón Giant-Tortoise and helping bring the Reptiles of Ecuador book project to life.

Click here to adopt a species.

Authors: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador. and Juan M GuayasaminbAffiliation: Laboratorio de Biología Evolutiva, Universidad San Francisco de Quito (USFQ), Quito, Ecuador.,cAffiliation: Galapagos Science Center, Galápagos, Ecuador.,dAffiliation: Centro de Investigación de la Biodiversidad y Cambio Climático, Universidad Tecnológica Indoamérica, Quito, Ecuador.

Academic reviewers: Adalgisa Caccone.

Photographers: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Arteaga A, Guayasamin JM (2020) Chelonoidis duncanensis. In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com

Literature cited:

- Heller E (1903) Papers from the Hopkins-Stanford Galápagos Expedition, 1898-1899. XIV. Reptiles. Proceedings of the Washington Academy of Sciences 5:39–98.

- Rodhouse P, Barling RWA, Clark WIC, Kinmonth AL, Mark AM, Roberts D, Armitage LE, Austin PR, Baldwin SP, Bellairs AD, Nightingale PJ (1975) The feeding and ranging behaviour of Galápagos giant tortoises (Geochelone elephantopus). The Cambridge and London University Galápagos Expeditions, 1972 and 1973. Journal of Zoology 176: 297–310.

- Snow DW (1964) The giant tortoises of the Galápagos Islands: their present status and future chances. Oryx 7: 277–290.

- Fritts TH, Fritts PR (1982) Race with extinction: herpetological notes of J. R. Slevin's journey to the Galápagos 1905–1906. Herpetological Monographs 1: 1–98.

- Cayot LJ (1987) Ecology of giant tortoises (Geochelone elephantopus) in the Galápagos Islands. PhD thesis, New York, United States, Syracuse University.

- MacFarland CG, Villa J, Toro B (1974) The Galápagos giant tortoises (Geochelone elephantopus). Part II: Conservation methods. Biological Conservation 6: 198–212.

- MacFarland CG, Reeder WG (1975) Breeding, raising and restocking of giant tortoises (Geochelone elephantopus) in the Galápagos Islands. In: Martin RD (Ed) Breding endangered species in captivity. Academic Press, New York, 13–36.

- Washington Tapia, unpublished data.

- Caporaso F (1991) The Galápagos tortoise conservation program: the plight and future for the Pinzón Island tortoise. In: Beaman RK, Caporaso F, McKeown S, Graff MD (Eds) Proceedings of the First International Symposium on Turtles and Tortoises. Chapman University, Los Angeles, 113–126.

- Gibbs JP, Caccone A, Cayot LJ, Tapia W (2017) Chelonoidis duncanensis. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org

- Townsend CH (1925) The Galápagos tortoises in their relation to the whaling industry: a study of old logbooks. Zoologica 4: 55–135.

- Oxford P, Watkins G (2009) Galapagos: both sides of the coin. Imagine Publishing, Morgansville, 256 pp.

- Pritchard PCH (1996) The Galápagos tortoises. Nomenclatural and survival status. Chelonian Research Monographs 1: 1–85.

- Swingland IR (1989) Geochelone elephantopus. Galápagos giant tortoises. In: Swingland IR, Klemens MW (Eds) The conservation biology of tortoises. Occasional Papers of the IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC), Gland, 24–28.

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington, 882 pp.