San Cristóbal Giant-Tortoise |

Reptiles of Ecuador | Testudines | Testudinidae | Chelonoidis chathamensis

English common names: San Cristóbal Giant-Tortoise, Chatham Island Giant-Tortoise.

Spanish common names: Galápago de San Cristóbal, tortuga gigante de San Cristóbal.

Recognition: ♂♂ 98.3 cm ♀♀ 89.7 cm. Chelonoidis chathamensis is a giant tortoise with a moderately saddlebacked carapace. It is the only species of giant tortoise known to occur on San Cristóbal Island.

Picture: Adult male. Galapaguera Cerro Colorado. Galápagos, Ecuador. | |

| |

Picture: Adult male. Galapaguera Cerro Colorado. Galápagos, Ecuador. | |

| |

Picture: Adult female. Galapaguera Cerro Colorado. Galápagos, Ecuador. | |

| |

Picture: Juvenile. Galapaguera Cerro Colorado. Galápagos, Ecuador. | |

| |

Picture: Hatchling. Galapaguera Cerro Colorado. Galápagos, Ecuador. | |

| |

Natural history: Common. Chelonoidis chathamensis is a diurnal and terrestrial tortoise that inhabits deciduous forests, dry shrublands, and dry grasslands.1 San Cristóbal Giant-Tortoises are active throughout the day, but rest in the shade2 during hot midday hours. The tortoises feed on herbaceous and shrubby vegetation1,3 and obtain water from their diet or from temporary pools.4 Juveniles of the San Cristóbal Giant-Tortoise stay in warmer lowland areas of the island during their first 10–15 years of life.5 As adults, they move across their elevation range, sometimes traveling 13 km in two days.2 When mating, the tortoises produce resounding guttural sounds.

"The terrapin resort to the low lands in the rainy season, drinking a sufficient quantity of water, at that time, to serve them during the dry season, which is six months. They then retreat to high ground, in consequence of which the labor of the ship's crew, who go there to collect them, is great; as they have to pass through a thicket of bushes for a mile or two before they can fall in with any of them.

Men have strayed away in these thickets, in search of terrapins, and not being able to find their way out, have perished there for the want of water. My sufferings in this particular, as well as those of some of my ship-mates, were great; and we at times were under the extreme necessity of drinking the blood of the terrapin, and even the water of the animal, whith which they like the camel abundantly provide themselves for the season."

Thomas Smith, whaler, 1821.6

Conservation: Endangered.3 Chelonoidis chathamensis is listed in this category because nearly 88% of the population disappeared over the last 180 years.3 The number of San Cristóbal Giant Tortoises declined catastrophically from about 24,000 to 500–700 individuals in the early 1970s.3,7 Historical causes of the population decline include extensive overexploitation for food by sailors (mostly whalers) and settlers5,6 and the introduction of exotic species (including goats, pigs, dogs, donkeys, and rodents), which either prey on the eggs and the hatchlings or destroy their habitat.5–8 The bulk of the decline occurred under the administration of Manuel Julián Cobos, the first owner of San Cristóbal Island, who exported tortoises to Guayaquil to produce oil.

"Arranging the total catch of tortoises by islands, we find Chatham (San Cristóbal) Island, with 4,798 far in the lead point of number (of tortoises) taken."

Charles Townsend, zoologist at the New York Aquarium, 1925.6

Nowadays, the population of Chelonoidis chathamensis is growing thanks to the head-starting program of the Galápagos National Park, in which young tortoises are raised in captivity and subsequently released into the wild. A census carried out in November 2016, estimated that 6,700 San Cristóbal Giant-Tortoises remain.3

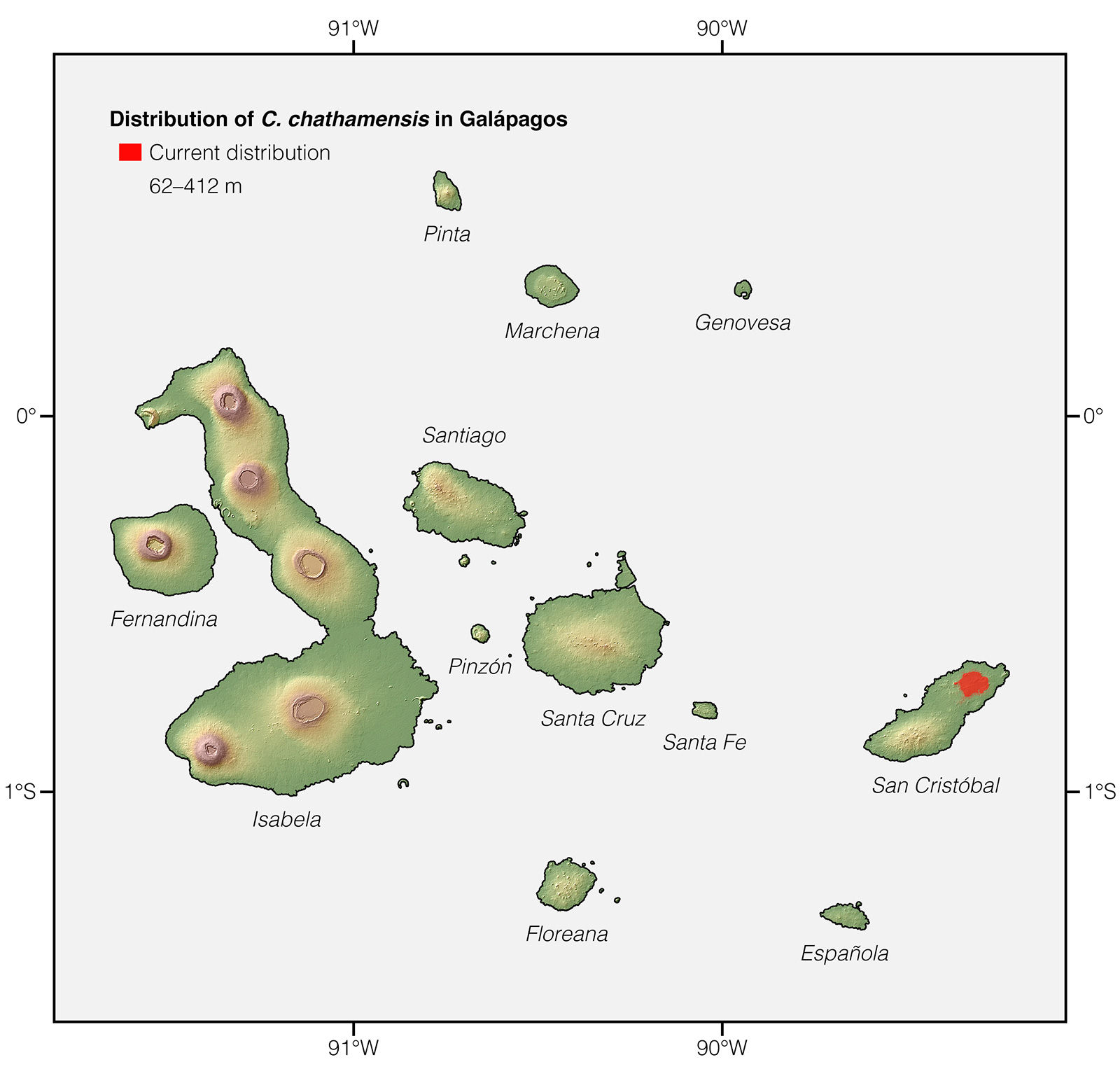

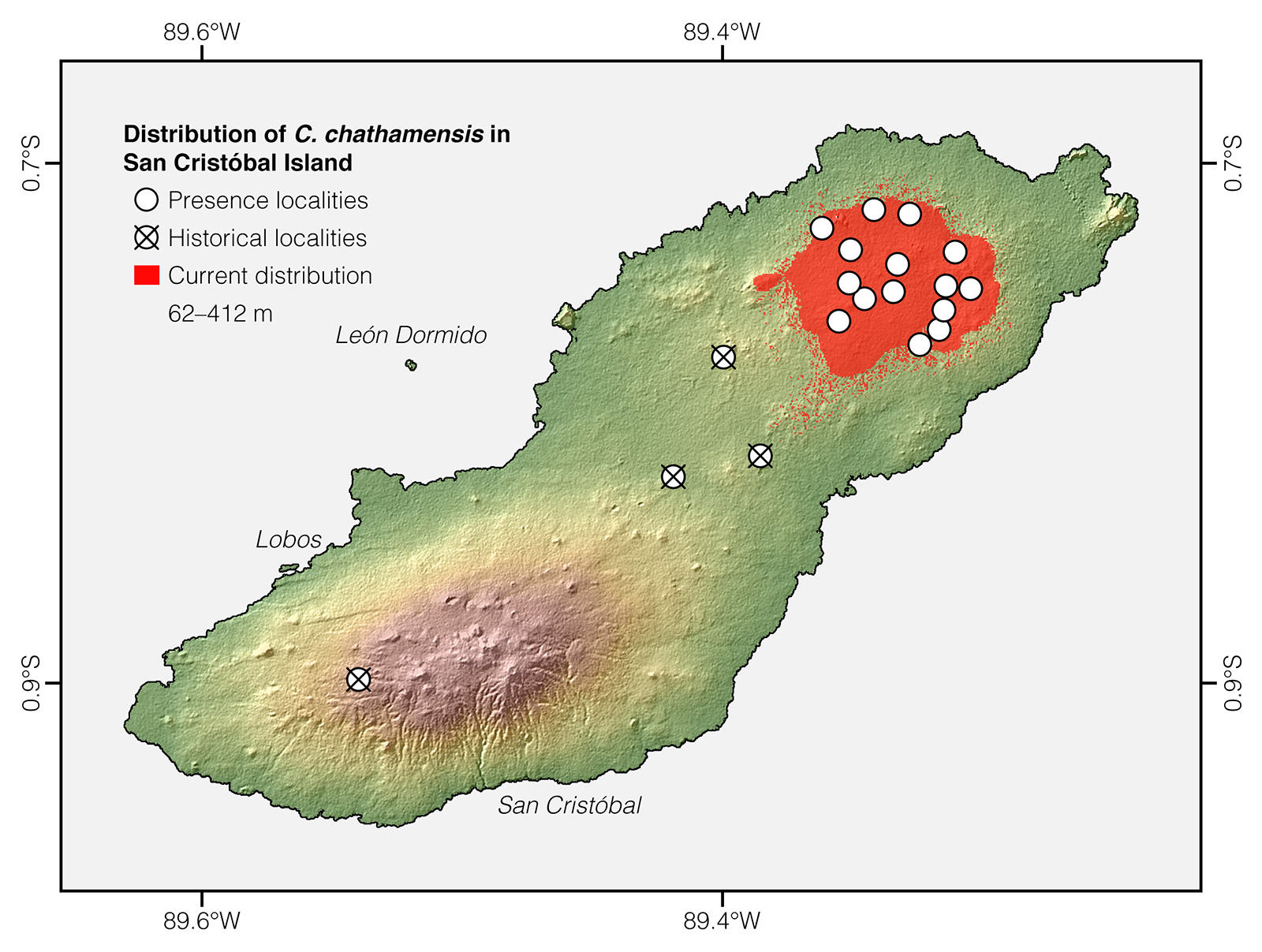

Distribution: Chelonoidis chathamensis is endemic to San Cristóbal Island in Galápagos, Ecuador. Historically, this species occurred throughout the island, but now wild tortoises persist only in an estimated 52 km2 area known as Galapaguera Natural, located in the northeast of the island.

Etymology: The generic name Chelonoidis comes from the Greek word chelone (meaning “tortoise”).9 The specific epithet chathamensis refers to San Cristóbal, previously known as Chatham Island.10

See it in the wild: Individuals of Chelonoidis chathamensis can be seen year-round with ~100% certainty at the Galapaguera Natural, located in the northeastern part of San Cristóbal Island. This is the only wild population accessible to tourism. The tortoises can also be seen at the Galapaguera Cerro Colorado, a seminatural breeding center managed by the Galápagos National Park.

This species has been symbolically adopted on behalf of Jacques Pierre Levy. Special thanks to Yaïr Levy for supporting the creation of this account and helping bring the Reptiles of Ecuador book project to life.

Click here to adopt a species.

Authors: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador. and Juan M GuayasaminbAffiliation: Laboratorio de Biología Evolutiva, Universidad San Francisco de Quito (USFQ), Quito, Ecuador.,cAffiliation: Galapagos Science Center, Galápagos, Ecuador.,dAffiliation: Centro de Investigación de la Biodiversidad y Cambio Climático, Universidad Tecnológica Indoamérica, Quito, Ecuador.

Academic reviewers: Adalgisa Caccone.

Photographers: Jose VieiraaAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,eAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Arteaga A, Guayasamin JM (2020) Chelonoidis chathamensis. In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com

Literature cited:

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- Evans LT, Quaranta JV (1951) A study of the social behavior of a captive herd of giant tortoises. Zoologica 36: 171–181.

- Caccone A, Cayot LJ, Gibbs JP, Tapia W (2017) Chelonoidis chathamensis. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org

- Slevin JR (1935) An account of the reptiles inhabiting the Galápagos Islands. Bulletin of the New York Zoological Society 38: 3–24.

- Swingland IR (1989) Geochelone elephantopus. Galápagos giant tortoises. In: Swingland IR, Klemens MW (Eds) The conservation biology of tortoises. Occasional Papers of the IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC), Gland, 24–28.

- Townsend CH (1925) The Galápagos tortoises in their relation to the whaling industry: a study of old logbooks. Zoologica 4: 55–135.

- MacFarland CG, Villa J, Toro B (1974) The Galápagos giant tortoises (Geochelone elephantopus). Part II: Conservation methods. Biological Conservation 6: 198–212.

- Márquez C, Wiedenfeld D, Snell H, Fritts T, MacFarland C, Tapia W, Naranjo S (2004) Estado actual de las poblaciones de tortugas terrestres gigantes (Geochelone spp., Chelonia: Testudinidae) en las islas Galápagos. Ecología Aplicada 3: 98–111.

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington, 882 pp.

- Van Denburgh J (1907) Expedition of the California Academy of Sciences to the Galápagos Islands, 1905-1906. I. Preliminary descriptions of four new races of gigantic land tortoises from the Galápagos Islands. Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences 1: 1–6.