Published March 20, 2023. Updated May 28, 2024. Open access. | Purchase book ❯ |

Brown Caiman (Caiman fuscus)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Crocodylia | Alligatoridae | Caiman fuscus

English common names: Brown Caiman, Central American Caiman.

Spanish common names: Caimán de la costa.

Recognition: ♂♂ 221 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. ♀♀ 177 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail..1,2 The Brown Caiman (Caiman fuscus) can be distinguished from Crocodylus acutus, the other crocodilian inhabiting the Ecuadorian coastal region, by having a bony inter-orbital ridge, a broad snout,3 and the fourth tooth on the lower jaw not visible when the mouth is closed (visible in C. acutus).4,5 The congeneric species C. crocodilus occurs on the Amazon basin of Ecuador and is characterized by having a narrower snout and two crests on the first 12–13 segments of the tail (instead of on the first 14–15 segments).5 Juveniles of C. fuscus are brown with blackish transverse bands on the body and tail. Adults are uniform dull pale olive brown (Fig. 1).3

Figure 1: Individuals of Caiman fuscus: coastal Ecuador (); Canopy Camp, Darién province, Panamá (). ad=adult; j=juvenile.

Natural history: With the exception of a few localities, Caiman fuscus is no longer a commonRecorded weekly in densities above five individuals per locality. species in western Ecuador. Brown Caimans are nocturnal, aquatic, and occur in a variety of freshwater habitats, including lagoons, lakes, swamps, marshes, rivers, and drainage canals,6,7 but also in brackish water (mangrove swamps and estuaries).4 They spend most of the time in the water but can also be seen basking on floating vegetation.8 Juveniles prefer shallower waters having abundant floating vegetation, where they wait in ambush for prey to pass by.5,9 Their diet at this stage is primarily composed of invertebrates, crustaceans, and frogs.6,10 Adults also feed on these prey items, but their diet is based primarily on fish and to a smaller degree on birds and small mammals.5–10 In captivity, individuals of C. fuscus reach sexual maturity at around three years old.2 Nesting takes place at the beginning of the rainy season in most studied populations,2,11 but in Ecuador it is unknown. Females build ~0.7–1 m tall mount-like nests using soil, twigs, and leaf-litter.6,11,12 These are located adjacent to, but not flooded by, rivers and water canals.11,12 Clutches consist of 17–40 eggs that have a mean length of 6.5 cm and take 73–90 days (about three months) to hatch.6,12 Hatchlings measure ~21–23 cm in total length at birth.6,12 Juveniles remain in groups for up to 1.5 years and communicate acoustically with their siblings and with the mother.12 Temperature during incubation determines the sex of the hatchlings: low and high temperatures produces females and mid-temperatures result in males.13 The most important predators of eggs are raccoons12 and tegus (genus Tupinambis).14 Crocodiles (Crocodylus acutus),15 and otters16 are known predators of adults and juveniles, respectively.

Conservation: Near Threatened Not currently at risk of extinction, but requires some level of management to maintain healthy populations.. Caiman fuscus has not been formally evaluated by the IUCN Red List, but it is here listed in the NT category. The rationale is that although the species is widely distributed and introduced in some areas, it has nevertheless suffered overexploitation in most countries where it occurs,17 including Ecuador, where most populations have been extirpated.9 The meat and eggs are consumed and the skin is used as material for handicrafts and various garments.5 Some populations are affected by mortality related to high speed boat traffic while others are experiencing adverse effects by accumulating mercury associated with artisanal and small-scale gold mining.18

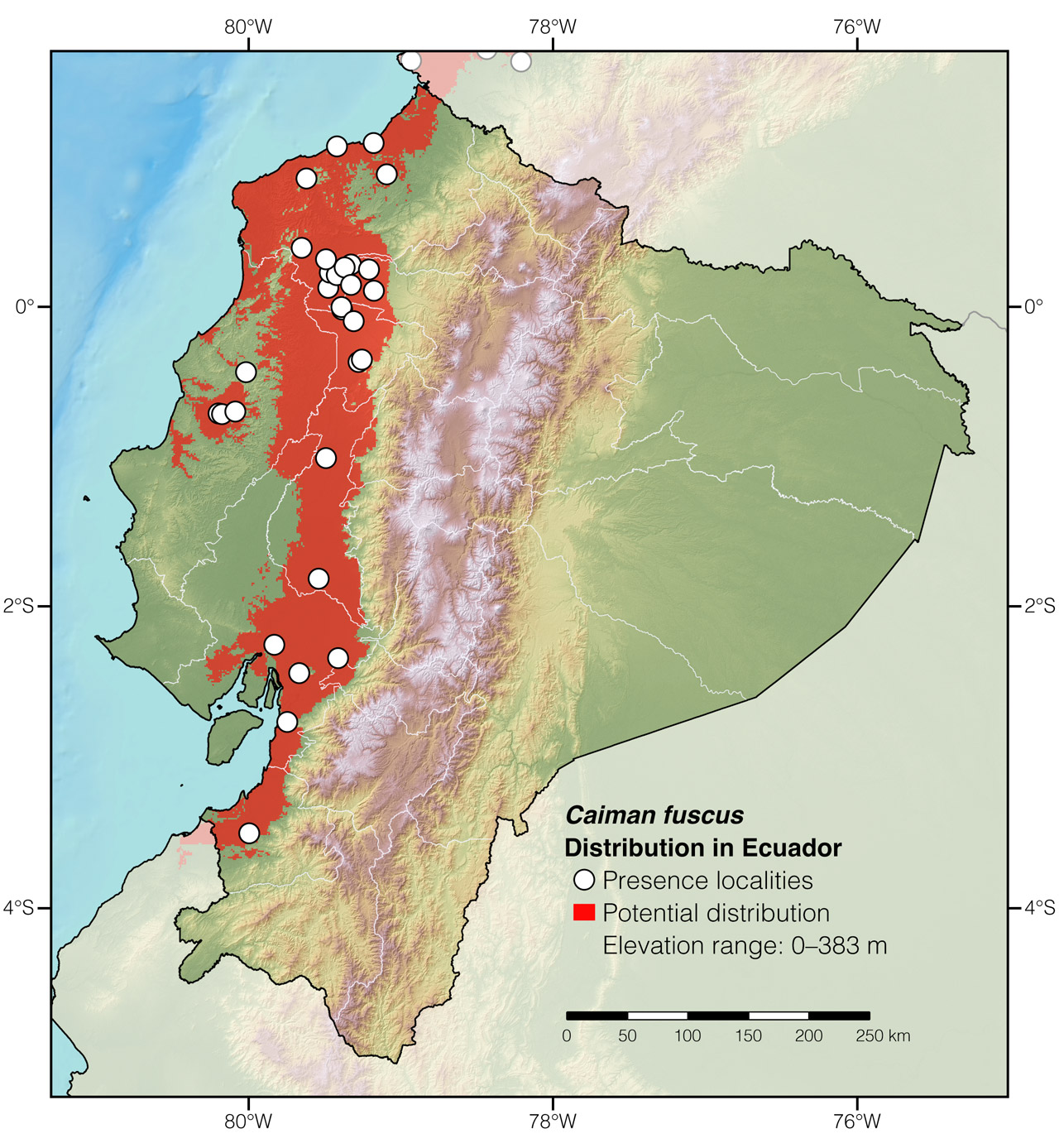

Distribution: Caiman fuscus is native to the Chocó–Río Magdalena valley and Mesoamerica biogeographic regions, from Honduras to northwestern Ecuador. The species has also been introduced and become established in Florida, Puerto Rico, Cuba, and San Andrés Island.10,19 In Ecuador, C. fuscus has only been recorded west of the Andes at elevations below 383 m (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Distribution of Caiman fuscus in Ecuador. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The name Caiman is thought to have originated from Cariban languages, specifically from the word acayouman, which is the name Arawak peoples may have used to refer to this group of crocodilians. The specific epithet fuscus is a Latin word meaning “dark” or “swarthy.”20 It refers to the dark coloration of the body in the holotype as well as in most adult individuals of this species.3

See it in the wild: Brown Caimans can be seen reliably in a few protected wetlands in western Ecuador, including Laguna de Cube, Humedal La Segua, and Humedal La Tembladera. Elsewhere in Ecuador, the species has been nearly extirpated. These reptiles are most easily found at night by detecting their bright orange eye-shine. However, in most areas, individuals are becoming increasingly wary of human presence, fleeing when approached.

Special thanks to James Scandol for symbolically adopting the Brown Caiman and helping bring the Reptiles of Ecuador book project to life.

Click here to adopt a species.

Notes: In this account, Caiman fuscus is treated as a full species rather than as a subspecies of C. crocodilus as a preliminary first step in recognizing its distinctiveness and solving the paraphyly of C. crocodilus.19,21

Acknowledgments: Special thanks to Ricardo Chiriboga and María Belén Chiriboga of Zoo el Pantanal for prodiving photographic access to specimens of Caiman fuscus under their care.

Author: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

Photographer: Jose VieirabAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,cAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Arteaga A (2024) Brown Caiman (Caiman fuscus). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/DKZU8617

Literature cited:

- Webb G, Brien M, Manolis C, Medrano-Bitar S (2012) Predicting total lengths of spectacled Caiman (Caiman crocodilus) from skin measurements: a tool for managing the skin trade. Herpetological Conservation and Biology 7: 16–26.

- Ramírez Pinilla MP (2003) Annual reproductive activity of Caiman crocodilus fuscus in captivity. Zoo Biology 22: 121–133.

- Cope ED (1868) On the crocodilian genus Perosuchus. Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 20: 203.

- Savage JM (2002) The amphibians and reptiles of Costa Rica, a herpetofauna between two continents, between two seas. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 934 pp.

- Morales-Betancourt MA, Lasso CA, De La Ossa V J, Fajardo-Patiño A (2013) Biología y conservación de los Crocodylia de Colombia. Serie Editorial Recursos Hidrobiológicos y Pesqueros Continentales de Colombia, Instituto de Investigación de Recursos Biológicos Alexander von Humboldt (IAvH), Bogotá, 335 pp.

- Ellis TM (1980) Caiman crocodilus: an established exotic in South Florida. Copeia 1980: 152–154. DOI: 10.2307/1444148

- Moreno-Arias RA, Ardila-Robayo MC, Martínez-Barreto W, Suárez-Daza RM (2013) Ecología poblacional de la babilla (Caiman crocodilus fuscus) en el valle del Río Magdalena (Cundinamarca, Colombia). Caldasia 35: 25–36.

- Krysko KL, Granatosky M, Fratto ZW, Kline JL, Rochford MR (2010) Caiman crocodilus (Spectacled Caiman): prey. Herpetological Review 41: 248–349.

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- Forero-Medina G, Castaño-Mora OV, Rodríguez-Melo M (2006) Ecology of Caiman crocodilus fuscus on San Andrés Island, Colombia: a preliminar study. Caldasia 28: 115–124.

- Aranda-Coello JM (2015) Nuevas observaciones sobre la ecología de anidación de Caiman crocodilus en Caño Negro, Costa Rica. Boletín de la Asociación Herpetológica Española 27: 26–29.

- Allsteadt J (1994) Nesting ecology of Caiman crocodilus in Caño Negro, Costa Rica. Journal of Herpetology 28: 12–19.

- Lang JW, Andrews HV (1994) Temperature-dependent sex determination in Crocodilians. The Journal of Experimental Zoology 270: 28–44.

- MINAMBIENTE (2016) Report from Colombia on Caiman crocodilus fuscus. CITES, Geneva, 16 pp.

- Medem F (1981) Los Crocodylia de Sur América. Volumen I. Los Crocodylia de Colombia. Colciencias, Bogotá, 354 pp.

- Medina-Barrios OD, Morales-Betancourt D (2015) Evento de depredación de Caiman crocodilus fuscus por Lontra longicaudis (Carnivora: Mustelidae) en el río Palomino, departamento de La Guajira, Colombia. Mammamology Notes 2: 19–20. DOI: 10.47603/manovol2n1.19-21

- Ross JP (1998) Crocodiles: status survey and conservation action plan. IUCN/SSC Crocodile Specialist Group, Gainesville, 97 pp.

- Marrugo-Negrete J, Durango-Hernández J, Calao-Ramos C, Urango-Cárdenas I, Díez S (2019) Mercury levels and genotoxic effect in caimans from tropical ecosystems impacted by gold mining. The Science of the Total Environment 10: 899–907. DOI: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.01.340

- Balaguera-Reina SA, Konvalina JD, Mohammed RS, Gross B, Vazquez R, Moncada JF, Ali S, Hoffman EA, Densmore LD (2021) From the river to the ocean: mitochondrial DNA analyses provide evidence of spectacled caimans (Caiman crocodilus Linnaeus 1758) mainland–insular dispersal. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 134: 486–497. DOI: 10.1093/biolinnean/blab094

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington D.C., 882 pp.

- Roberto IJ, Fedler MT, Hrbek T, Izeni F, Blackburn DC (2021) The taxonomic status of Florida Caiman: a molecular reappraisal. Journal of Herpetology 55: 279–284. DOI: 10.1670/20-026

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Caiman fuscus in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Colombia | Cauca | Guapi | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Colombia | Nariño | Bajo Cumilinche | UPTC 2019 |

| Colombia | Nariño | Laguna Chimbusa | IAvH-R-4394; Borja-Acosta & Galeano Muñoz 2023 |

| Colombia | Nariño | Payan | Jiménez Alonso 2016 |

| Colombia | Valle del Cauca | Río Raposo | USNM 151748; VertNet |

| Ecuador | El Oro | Humedal La Tembladera | Carabajo 2010 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Bosque Protector La Perla | Photo by Plácido Palacios |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Hacienda Cucaracha | Observation by AA |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Hacienda Erazo | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | La Concordia | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | La Marujita | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | La Quinta | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Laguna de Cube | Photo by Francisco Sornoza |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Las Peñas | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Río Blanco | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Río Esmeraldas | Rhodin et al. 2009 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Río Quinindé | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Río Verde | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | San Francisco de Onzole | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Balao Chico | Montero Recalde & Lescano Ocaña 2016 |

| Ecuador | Guayas | El Triunfo | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Manglares Churute | Dirección Zonal 5 MAATE |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Río Guayas | Jiménez Alonso 2016 |

| Ecuador | Los Ríos | Babahoyo | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Los Ríos | Humedal La Segua | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Los Ríos | San Rafael | MAATE Los Ríos 2022 |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Humedal La Segua, San Antonio | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Río Chone | El Diario de Chone 2012 |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Zapallo | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Cacao de la Loma | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | El Tesoro | Photo by Andreas Kay |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Piedra de Vapor | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Santo Domingo de los Tsáchilas | Finca La Floreana | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Santo Domingo de los Tsáchilas | Puerto Naranjo | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Santo Domingo de los Tsáchilas | Valle Hermoso | iNaturalist; photo examined |