Osborne's Lancehead |

Reptiles of Ecuador | Serpentes | Viperidae | Bothrops osbornei

English common names: Osborne's Lancehead.

Spanish common names: Llucti negra, equis de Osborne.

Recognition: ♂♂ 133 cm ♀♀ 144 cm. In its area of distribution, the Osborne's Lancehead (Bothrops osbornei) may be recognized by its triangular-shaped head with symmetrical dark brown markings,1 heat-sensing pits between the eyes and nostrils, prehensile (capable of grasping) tail, and pattern of dark brown trapezoidal blotches on a yellow (in juveniles) to brown (in adults) dorsum. The most similar viper is B. punctatus, which has a

Picture: Adult from Mindo, Pichincha, Ecuador. | |

| |

Picture: Adult from Mindo, Pichincha, Ecuador. | |

| |

Picture: Juvenile from Mashpi Reserve, Pichincha, Ecuador. | |

| |

Picture: Juvenile from Mindo, Pichincha, Ecuador. | |

| |

Natural history: Rare to uncommon.3 Bothrops osbornei is a semiarboreal snake that inhabits old-growth to moderately disturbed evergreen montane forests, forest borders, and pastures with scattered trees.4,5 Osborne's Lanceheads are active at night or at dusk, especially after a warm day.5 They spend most of their time coiled at ground level or perched on vegetation up to 3.5 m above the ground.5 During the daytime, individuals have been found resting on rocks, on vegetation, or hidden among tall grass or under logs.5 Osborne's Lanceheads are ambush predators. As juveniles, they feed on frogs (among them, Pristimantis achatinus),3,5 which they attract by means of moving their brightly colored tail as a lure.5 Adults feed on rodents.3

Individuals of Bothrops osbornei rely on their camouflage as a primary defense mechanism, but may readily bite if attacked or harassed.5 Bothrops osbornei is a venomous snake (LD50 2.6 mg/kg).6 In humans, its venom causes intense pain, bleeding, necrosis (death of cells and muscle tissue),3,6 and presumably also death. Females of this species “give birth” (the eggs hatch within the mother) to 14–27 young that are 27.5–29.4 cm in total length.3

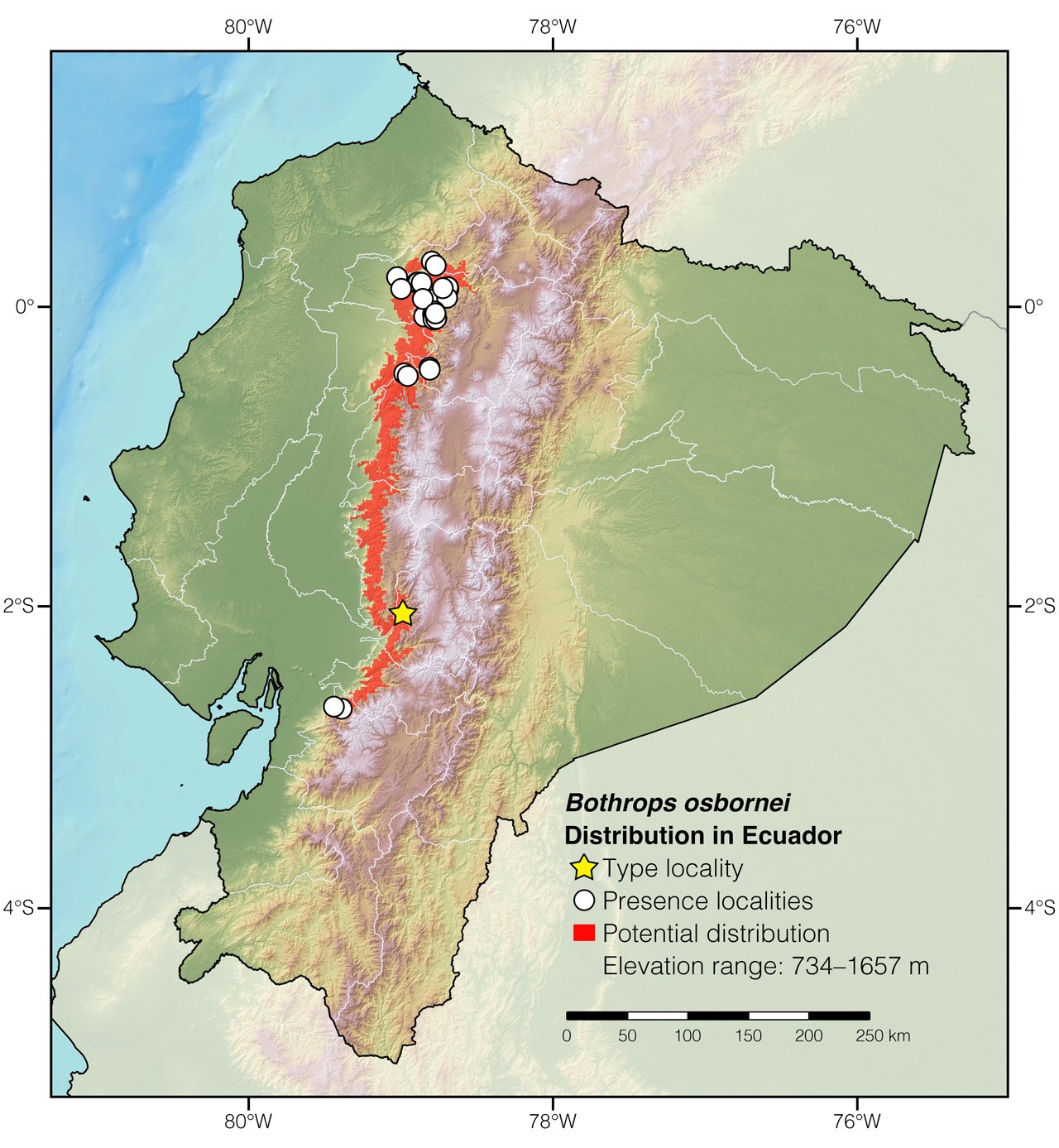

Conservation: Vulnerable.7 Bothrops osbornei is listed in this category because the species has a limited geographic distribution and its habitat is declining in extent and quality due to deforestation.3,5 We estimate that ~61% of the habitat of B. osbornei has already been destroyed. In addition to habitat loss, the species faces the threat of direct killing5 and traffic mortality.8

Distribution: Bothrops osbornei is endemic to an estimated 7,498 km2 area in the western slopes of the Andes in central Ecuador.

Etymology: The generic name Bothrops, which is derived from the Greek word bothros (meaning “pit”),9 refers to the heat-sensing pits between the eyes and nostrils. The specific epithet osbornei honors Steven Osborne, a colleague of the biologist who described the species.1

See it in the wild: Osborne's Lanceheads can be located with ~1–2% certainty in forested areas in the north of the species' area of distribution. Some of the best localities to find Osborne's Lanceheads are Mindo and Mashpi Rainforest Reserve.

Special thanks to Claudio Moro for symbolically adopting the Osborne’s Lancehead and helping bring the Reptiles of Ecuador book project to life.

Click here to adopt a species.

Author: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

Photographers: Jose Vieira,aAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,bAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador. Alejandro Arteaga,aAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador. and Frank PichardoaAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Arteaga A (2020) Bothrops osbornei. In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com

Literature cited:

- Campbell JA, Lamar WW (2004) The venomous reptiles of the western hemisphere. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, 774 pp.

- Arteaga A, Pyron RA, Peñafiel N, Romero-Barreto P, Culebras J, Bustamante L, Yánez-Muñoz MH, Guayasamin JM (2016) Comparative phylogeography reveals cryptic diversity and repeated patterns of cladogenesis for amphibians and reptiles in northwestern Ecuador. PLoS ONE 11: e0151746.

- Valencia JH, Garzón-Tello K, Barragán-Paladines ME (2016) Serpientes venenosas del Ecuador: sistemática, taxonomía, historial natural, conservación, envenenamiento y aspectos antropológicos. Fundación Herpetológica Gustavo Orcés, Quito, 653 pp.

- Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Guayasamin JM (2013) The amphibians and reptiles of Mindo. Universidad Tecnológica Indoamérica, Quito, 257 pp.

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- Kuch U, Mebs D, Gutiérrez JM, Freire A (1996) Biochemical and biological characterization of the Ecuadorian pitvipers (genera Bothriechis, Bothriopsis, Bothrops, and Lachesis). Toxicon 34: 714–717.

- Yánez-Muñoz MH, Brito J (2019) Bothrops osbornei. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org

- Field notes of Mike Knoerr.

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington D.C., 882 pp.