Published July 18, 2023. Updated November 20, 2023. Open access. Peer-reviewed. | Purchase book ❯ |

Striped Bachia (Bachia trisanale)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Sauria | Gymnophthalmidae | Bachia trisanale

English common names: Striped Bachia, Stacy’s Bachia.

Spanish common names: Lagartija amazónica de patas cortas.

Recognition: ♂♂ 18.0 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=7.2 cm. ♀♀ 19.9 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=7.9 cm..1,2 This wormlike microteiid is unmistakable among leaf-litter lizards in the Ecuadorian Amazon by lacking an external ear and by having rudimentary forelimbs and hind limbs reduced to extremely short stubs.1–4 Older individuals may have no hind limbs at all. The dorsal surfaces are light tan with a series of blackish longitudinal lines alternating with pale lines (Fig. 1).4 No other lizard in Ecuador fits this description.

Figure 1: Individuals of Bachia trisanale from Canelos, Pastaza province, Ecuador.

Natural history: Bachia trisanale is a rarely encountered lizard that inhabits old growth terra-firme rainforests.2,3 The species also occurs in forest edges, clearings, and human residential areas.1–4 Striped Bachias are diurnal and primarily fossorial.5 Individuals have been dug out of sandy soil,1 taken from beneath or inside decaying logs, and found in leaf-litter.2,3 They are occasionally seen above the ground on leaf-litter, grass,2 in trenches,1 or collected in pitfall traps.5 The diet in this species includes beetles and their larvae, earthworms, termites, and centipedes.1,2 When startled, these reptiles move in an erratic way and quickly take refuge in the leaf-litter. They are also quick to shed their fragile tail as a distraction to predators.5 There are records of snakes (Micrurus helleri,6 Siphlophis cervinus,1 and Taeniophallus occipitalis2) preying upon individuals of B. trisanale.1 Gravid females containing two oviductal eggs have been found in Ecuador1,7 and Peru,2,3 but the real clutch size is not known.

Conservation: Least Concern Believed to be safe from extinction given current circumstances..8 Bachia trisanale is included in this category mainly on the basis of the species’ wide distribution throughout the Amazon basin, its presence in protected areas, and lack of major widespread threats. The comparatively low number of records of B. trisanale throughout its range seems to be due to the species’ fossorial habits rather than to actual low population densities.

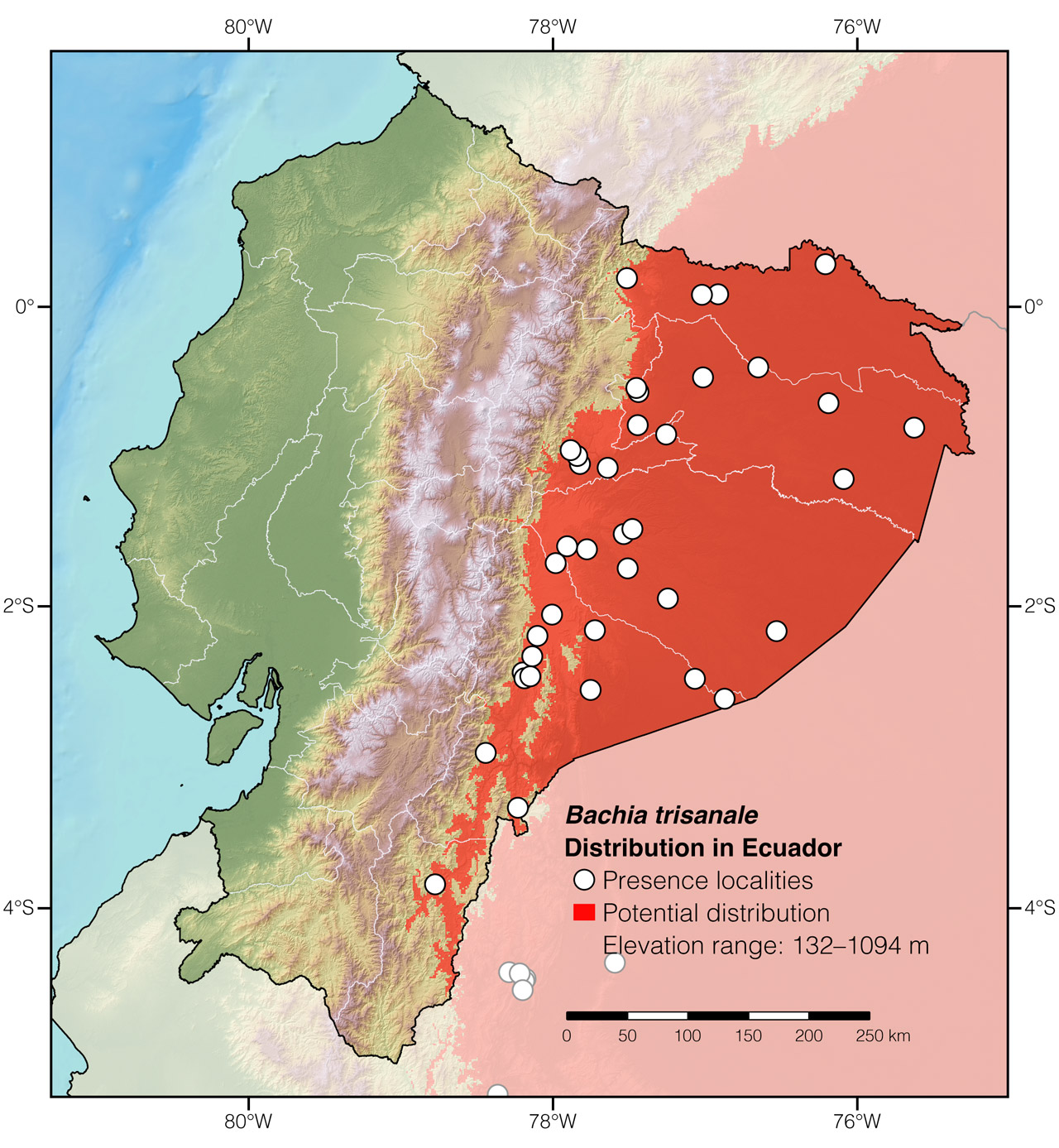

Distribution: Bachia trisanale is native to the western Amazon basin in Brazil, Ecuador (Fig. 2), and Perú.9

Figure 2: Distribution of Bachia trisanale in Ecuador. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The generic name Bachia does not appear to be a reference to any feature of this group of lizards, but a matter of personal taste. John Edward Gray usually selected girls’ names to use on reptiles.10–13 The specific epithet trisanale comes from the Latin words tris (=three)14 and anus, and refers to the number of parallel anal plates in this species.15

See it in the wild: Due to their fossorial habits, Striped Bachias are unlikely to be seen by most visitors to the Amazon rainforest in Ecuador. Although these shy reptiles may occasionally be seen crawling at surface level, they are most easily found by actively raking the leaf-litter or by turning over logs along primary rainforest trails. In Ecuador, the area having the greatest number of Bachia trisanale observations is the valley of the Río Upano, near the city Macas.

Author: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

Academic reviewer: Jeffrey D CamperbAffiliation: Department of Biology, Francis Marion University, Florence, USA.

Photographer: Jose VieiracAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,dAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Arteaga A (2023) Striped Bachia (Bachia trisanale). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/VIAH8106

Literature cited:

- Duellman WE (1978) The biology of an equatorial herpetofauna in Amazonian Ecuador. Publications of the Museum of Natural History, University of Kansas 65: 1–352.

- Duellman WE (2005) Cusco amazónico: the lives of amphibians and reptiles in an Amazonian rainforest. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, 433 pp.

- Dixon JR, Soini P (1986) The reptiles of the upper Amazon Basin, Iquitos region, Peru. Milwaukee Public Museum, Milwaukee, 154 pp.

- Dixon JR (1973) A systematic review of the teiid lizards, genus Bachia, with remarks on Heterodactylus and Anotosaura. Miscellaneous Publications of the Museum of Natural History, University of Kansas 57: 1–47.

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- Roze JA (1996) Coral snakes of the Americas: biology, indentification, and venoms. Krieger Publishing Company, Malabar, 328 pp.

- Almendáriz A (1987) Contribución al conocimiento de la herpetofauna centroriental Ecuatoriana. Revista Politécnica 12: 77–133.

- Aparicio J, Avila-Pires TCS, Moravec J, Perez P (2019) Bachia trisanale. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org. DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-2.RLTS.T178683A44956726.en

- Ribeiro-Junior MA, Amaral S (2017) Catalogue of distribution of lizards (Reptilia: Squamata) from the Brazilian Amazonia. IV. Alopoglossidae, Gymnophthalmidae. Zootaxa 4269: 151–196. DOI: 10.11646/zootaxa.4269.2.1

- Gray JE (1831) Description of a new genus of ophisaurean animal, discovered by the late James Hunter in New Holland. Treuttel, Würtz & Co., London, 40 pp.

- Gray JE (1831) A synopsis of the species of the class Reptilia. In: Griffith E, Pidgeon E (Eds) The animal kingdom arranged in conformity with its organization. Whittaker, Treacher, & Co., London, 1–110.

- Gray JE (1838) Catalogue of the slender-tongued saurians, with descriptions of many new genera and species. Annals and Magazine of Natural History 1: 274–283.

- Gray JE (1945) Catalogue of the specimens of lizards in the collection of the British Museum. Trustees of the British Museum, London, 289 pp.

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington D.C., 882 pp.

- Cope ED (1868) An examination of the Reptilia and Batrachia obtained by the Orton Expedition to Equador and the Upper Amazon, with notes on other species. Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 20: 96–140.

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Bachia trisanale in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Chiguaza | USNM 163449; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Comunidad Shuar Kunkuk | QCAZ 16101; Carvajal-Campos 2020 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Finca El Piura | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Limón | KU 154665; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Macas | Dixon 1973 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Macuma | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Río Cusuime | Ortega-Andrade 2010 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Río Guachirpasa | Ortega-Andrade 2010 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Shuin Mamus | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Sucúa | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Sucúa, 3.2 km E of | Dixon 1973 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Turula | AMNH 14574; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Napo | Estación Biológica Jatun Sacha | Vigle 2008 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Hacienda George Kiederle | USNM 196073; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Napo | Huella Verde Lodge | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Napo | Río Pucuno | USNM 196074; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Napo | San José Viejo de Sumaco | USNM 524104; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Napo | Tena | Dixon 1973 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Universidad Ikiam | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Napo | Yachana Reserve | Beirne et al. 2013 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | El Coca | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Reserva Río Bigal | García et al. 2021 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Río Cononaco | Peracca 1897 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Río Nashiño | QCAZ 5491; Carvajal-Campos 2020 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Sector San Carlos | QCAZ 14616; Carvajal-Campos 2020 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Tiputini Biodiversity Station | Cisneros-Heredia 2003 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Chontoa | Ortega-Andrade 2010 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Palora | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Pozo Petrolero Misión | Almendáriz 1987 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Villano | Ortega-Andrade 2010 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Sarayacu | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Teresa Mama | USNM 196077; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Blanca | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Lago Agrio | Duellman 1973 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Limoncocha Biological Reserve | UIMNH 54381; collection database |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Puerto Libre | KU 122194; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Santa Cecilia | Duellman 1978 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Yantzaza | UMMZ 82875; VertNet |

| Perú | Amazonas | Aintami | MVZ 163080; VertNet |

| Perú | Amazonas | Aramango, 5 km NE of | LSUMZ 19631; VertNet |

| Perú | Amazonas | Chiriaco, 13 km SW of | LSUMZ 19633; VertNet |

| Perú | Amazonas | Huambisa Village | MVZ 174853; VertNet |

| Perú | Amazonas | Huampami | MCZ 182068; VertNet |

| Perú | Amazonas | Kayamas | USNM 316773; VertNet |

| Perú | Amazonas | La Poza | MVZ 174851; VertNet |

| Perú | Amazonas | Paagat | USNM 316777; VertNet |

| Perú | Amazonas | Pais | Lee et al. 2018 |

| Perú | Amazonas | Shiringa | USNM 568722; VertNet |

| Perú | Amazonas | Sua, on the Río Cenepa | USNM 316775; VertNet |

| Perú | Loreto | Cerro de Kampankis | Catenazzi & Venegas 2016 |

| Perú | Loreto | Santa María | TCWC 43343; VertNet |